In the latest of an occasional series remembering the crucially important role fishermen immediately took on a century ago, John Worrall looks back on how U-boats replaced herring as the sole target species of drifters.

It sort of made sense.

If peacetime drifters worked cotton nets up to a mile long to catch herring, it was presumably possible to catch a U-boat with something lengthy but more substantial. So they had a go.

The main fishing swim was the Dover Strait, through which many U-boats passed from their bases in the Flemish ports of Zeebrugge, Bruges and Ostend to attack Britain’s maritime supply lines. When war broke out, no one was taking the still primitive submarines very seriously, but after U9 took just an hour to sink three obsolete British cruisers, ominously known as the ‘Live Bait Squadron’, everyone took them seriously.

A dozen new Tribal class destroyers were already based at Dover, forming the nucleus of the Dover Patrol, and they were soon joined by 20 steam drifters, and then another 10, on mine detection and clearance and the directing of shipping through minefields. Those drifters were some of the more than a thousand which joined the WW1 fight, over 500 of them from Lowestoft and Yarmouth. Many came with their fishing crews, particularly the older fishermen, drafted into the Trawler Section of the Royal Naval Reserve, formed in 1911 primarily as an auxiliary mine-sweeping force.

The Dover Patrol developed the idea of steel nets with mines attached, deployed and attended by drifters, supported in turn by destroyers, although it was easier said than done. The Strait was only 20 miles wide but the water was difficult, with sandbanks, tidal rips and, in bad weather, breaking seas, all combining occasionally to sweep nets away. And British mines, yet to adopt the Herz horn firing system (see ‘Cracking Eggs’, Fishing News, 17 December) were notoriously unreliable and also tended to break loose and tangle in the nets.

And so U-boats, improving more rapidly than observation and detection devices, continued to get through, even if, with that much attention, some took the much longer route to the Atlantic around the north of Scotland, which limited their endurance. By the second half of 1915, the smaller, mine-laying UC-class U-boats were also adding their own mines to the mix, on an almost daily basis. On October 12, they claimed the Yarmouth drifter, Frons Olivae YH 217, off North Foreland and, a few days later, the Fraserburgh boat, Star of Buchan FR 534, just east of Isle of Wight. The following February the Kessingland-owned Persistive LT 42, was mined off Dover.

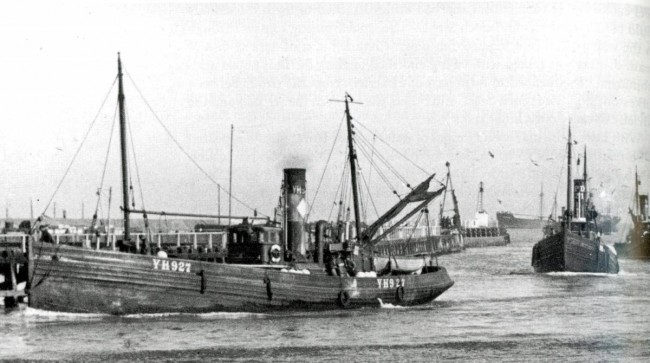

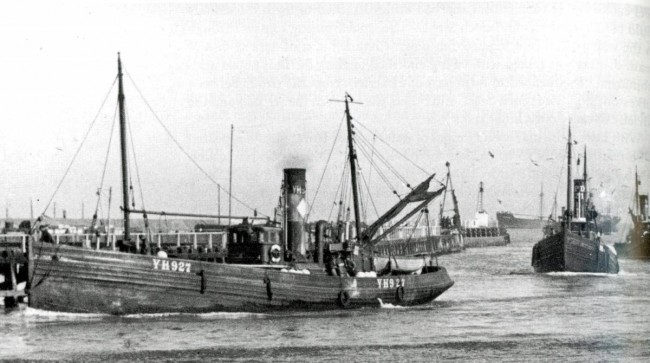

The wooden drifter Ma Freen YH 927, seen here entering Yarmouth, went tin fishing and got a bite. (Image courtesy of Port of Lowestoft Research Society).

Nevertheless, the nets caught a few, or led to their capture. When U8 left Ostend on March 4, 1915, it was spotted by the destroyer HMS Viking, which opened fire, making it dive. Shortly afterwards, the wooden Yarmouth drifter Ma Freen YH 927 saw the buffs supporting the top of its net moving east at four knots, and signalled to Captain CD Johnson, commander of the Dover destroyers, aboard HMS Maori.

An hour later, the Whitby drifter Roburn WY137 also got a bite, its indicator buoys being towed rapidly, and the destroyer HMS Ghurka fired an explosive sweep – a loop of cable bearing charges of electrically detonated guncotton – across the U-boat’s course. This created havoc inside the submarine, which began to leak badly and was soon end-up, its batteries spilling acid that reacted with seawater to produce chlorine gas, forcing it to the surface. When it then came under destroyer fire, its captain scuttled and he and his crew were taken prisoner.

Another Dover barrage-drifter, the Lowestoft boat, Gleaner of the Sea LT1170, had a closer encounter on April 24, 1916, when a U-boat fouled its anchor cable and then became entangled in its net. As the U-boat lay beneath the drifter, skipper Robert Hurren threw a lance bomb – a primitive anti-submarine weapon, deployed like an ancient whale harpoon – onto its foredeck and sank it.

On 27 October 1916, Roburn and Gleaner of the Sea were both sunk, along with four other drifters, all from Lowestoft, when destroyers attacked the boom drifters, killing 43 driftermen. When the accompanying old C-class destroyer, HMS Flirt, stopped to pick men from the water, she too was sunk with the loss of a further 60 lives, her only survivors being those in the rescue boats.

Wooden drifters, though nearly always obliterated by a mine, could nevertheless soak up punishment if luck was with them. On 18 March 1917, Redwald LT 1171 was hit off Dover by six destroyer shells, and still managed to beach and survive to return to her owner after the war.

But 1917 was a bad year for Allied shipping losses, because U-boats were still getting through, mostly on the surface at night and thereby mostly avoiding the nets. The attending drifters hadn’t yet taken to using searchlights because the Dover Patrol’s then commander Admiral Sir Reginald Bacon reckoned it would make them vulnerable to attack, although later testimony from a U-boat captain said that periscopes were pretty much blinded by multiple searchlights.

The scale of the traffic became apparent when documents retrieved from UC44, sunk by one of its own mines off Ireland in August 1917, suggested that between 20 and 30 were getting through each month. Those documents also included orders that U-boats should indeed pass on the surface at night, or dive to 40 metres, while any taking the northern route should do so as visibly as possible, to persuade the Allies that most were going that way.

And then, when an Admiralty committee went to inspect the barrage, the 1800-ton, 30-knot destroyer carrying them, inadvertently ran over one of the mined nets without causing an explosion. This was not an efficient barrier.

But detection technology was catching up. In late 1917, a hydrophone system showed promise although, trialled in the Firth of Forth, it was plagued by interference which abated only in early morning. It took a week for scientists to work out that the interference coincided with the schedule of the Edinburgh to Leith tramway but, away from the trams, the technology did work.

At the same time, Admiral Bacon installed a more comprehensive barrage involving 39,000 contact mines of the H2 and H4 type with the Herz horn which, together with the introduction of searchlights and flares for drifters, reduced U-boat traffic considerably.

But it was a bit late. October that year had seen 350,000 tonnes of shipping lost in the Channel and Western Approaches alone, and Bacon was replaced before the end of the war.

Further reading:

The Hidden Threat, the story of mines and minesweeping by the Royal Navy in World War 1, by Jim Crossley. Pen & Sword pen-and-sword.co.uk

North Sea War 1914-1919 by Robert Malster. Poppyland Publishing poppyland.co.uk

Read more from Fishing News here.

In the latest of an occasional series remembering the crucially important role fishermen immediately took on a century ago, John Worrall looks back on how U-boats replaced herring as the sole target species of drifters.

It sort of made sense.

If peacetime drifters worked cotton nets up to a mile long to catch herring, it was presumably possible to catch a U-boat with something lengthy but more substantial. So they had a go.

The main fishing swim was the Dover Strait, through which many U-boats passed from their bases in the Flemish ports of Zeebrugge, Bruges and Ostend to attack Britain’s maritime supply lines. When war broke out, no one was taking the still primitive submarines very seriously, but after U9 took just an hour to sink three obsolete British cruisers, ominously known as the ‘Live Bait Squadron’, everyone took them seriously.

A dozen new Tribal class destroyers were already based at Dover, forming the nucleus of the Dover Patrol, and they were soon joined by 20 steam drifters, and then another 10, on mine detection and clearance and the directing of shipping through minefields. Those drifters were some of the more than a thousand which joined the WW1 fight, over 500 of them from Lowestoft and Yarmouth. Many came with their fishing crews, particularly the older fishermen, drafted into the Trawler Section of the Royal Naval Reserve, formed in 1911 primarily as an auxiliary mine-sweeping force.

The Dover Patrol developed the idea of steel nets with mines attached, deployed and attended by drifters, supported in turn by destroyers, although it was easier said than done. The Strait was only 20 miles wide but the water was difficult, with sandbanks, tidal rips and, in bad weather, breaking seas, all combining occasionally to sweep nets away. And British mines, yet to adopt the Herz horn firing system (see ‘Cracking Eggs’, Fishing News, 17 December) were notoriously unreliable and also tended to break loose and tangle in the nets.

And so U-boats, improving more rapidly than observation and detection devices, continued to get through, even if, with that much attention, some took the much longer route to the Atlantic around the north of Scotland, which limited their endurance. By the second half of 1915, the smaller, mine-laying UC-class U-boats were also adding their own mines to the mix, on an almost daily basis. On October 12, they claimed the Yarmouth drifter, Frons Olivae YH 217, off North Foreland and, a few days later, the Fraserburgh boat, Star of Buchan FR 534, just east of Isle of Wight. The following February the Kessingland-owned Persistive LT 42, was mined off Dover.

The wooden drifter Ma Freen YH 927, seen here entering Yarmouth, went tin fishing and got a bite. (Image courtesy of Port of Lowestoft Research Society).

Nevertheless, the nets caught a few, or led to their capture. When U8 left Ostend on March 4, 1915, it was spotted by the destroyer HMS Viking, which opened fire, making it dive. Shortly afterwards, the wooden Yarmouth drifter Ma Freen YH 927 saw the buffs supporting the top of its net moving east at four knots, and signalled to Captain CD Johnson, commander of the Dover destroyers, aboard HMS Maori.

An hour later, the Whitby drifter Roburn WY137 also got a bite, its indicator buoys being towed rapidly, and the destroyer HMS Ghurka fired an explosive sweep – a loop of cable bearing charges of electrically detonated guncotton – across the U-boat’s course. This created havoc inside the submarine, which began to leak badly and was soon end-up, its batteries spilling acid that reacted with seawater to produce chlorine gas, forcing it to the surface. When it then came under destroyer fire, its captain scuttled and he and his crew were taken prisoner.

Another Dover barrage-drifter, the Lowestoft boat, Gleaner of the Sea LT1170, had a closer encounter on April 24, 1916, when a U-boat fouled its anchor cable and then became entangled in its net. As the U-boat lay beneath the drifter, skipper Robert Hurren threw a lance bomb – a primitive anti-submarine weapon, deployed like an ancient whale harpoon – onto its foredeck and sank it.

On 27 October 1916, Roburn and Gleaner of the Sea were both sunk, along with four other drifters, all from Lowestoft, when destroyers attacked the boom drifters, killing 43 driftermen. When the accompanying old C-class destroyer, HMS Flirt, stopped to pick men from the water, she too was sunk with the loss of a further 60 lives, her only survivors being those in the rescue boats.

Wooden drifters, though nearly always obliterated by a mine, could nevertheless soak up punishment if luck was with them. On 18 March 1917, Redwald LT 1171 was hit off Dover by six destroyer shells, and still managed to beach and survive to return to her owner after the war.

But 1917 was a bad year for Allied shipping losses, because U-boats were still getting through, mostly on the surface at night and thereby mostly avoiding the nets. The attending drifters hadn’t yet taken to using searchlights because the Dover Patrol’s then commander Admiral Sir Reginald Bacon reckoned it would make them vulnerable to attack, although later testimony from a U-boat captain said that periscopes were pretty much blinded by multiple searchlights.

The scale of the traffic became apparent when documents retrieved from UC44, sunk by one of its own mines off Ireland in August 1917, suggested that between 20 and 30 were getting through each month. Those documents also included orders that U-boats should indeed pass on the surface at night, or dive to 40 metres, while any taking the northern route should do so as visibly as possible, to persuade the Allies that most were going that way.

And then, when an Admiralty committee went to inspect the barrage, the 1800-ton, 30-knot destroyer carrying them, inadvertently ran over one of the mined nets without causing an explosion. This was not an efficient barrier.

But detection technology was catching up. In late 1917, a hydrophone system showed promise although, trialled in the Firth of Forth, it was plagued by interference which abated only in early morning. It took a week for scientists to work out that the interference coincided with the schedule of the Edinburgh to Leith tramway but, away from the trams, the technology did work.

At the same time, Admiral Bacon installed a more comprehensive barrage involving 39,000 contact mines of the H2 and H4 type with the Herz horn which, together with the introduction of searchlights and flares for drifters, reduced U-boat traffic considerably.

But it was a bit late. October that year had seen 350,000 tonnes of shipping lost in the Channel and Western Approaches alone, and Bacon was replaced before the end of the war.

Further reading:

The Hidden Threat, the story of mines and minesweeping by the Royal Navy in World War 1, by Jim Crossley. Pen & Sword pen-and-sword.co.uk

North Sea War 1914-1919 by Robert Malster. Poppyland Publishing poppyland.co.uk

Read more from Fishing News here.