In Remembrance week, John Worrall looks back at the start of the hostilities in the North Sea following the outbreak of World War One and, in the third of an occasional series, remembers the crucially important role fishermen immediately took on a century ago.

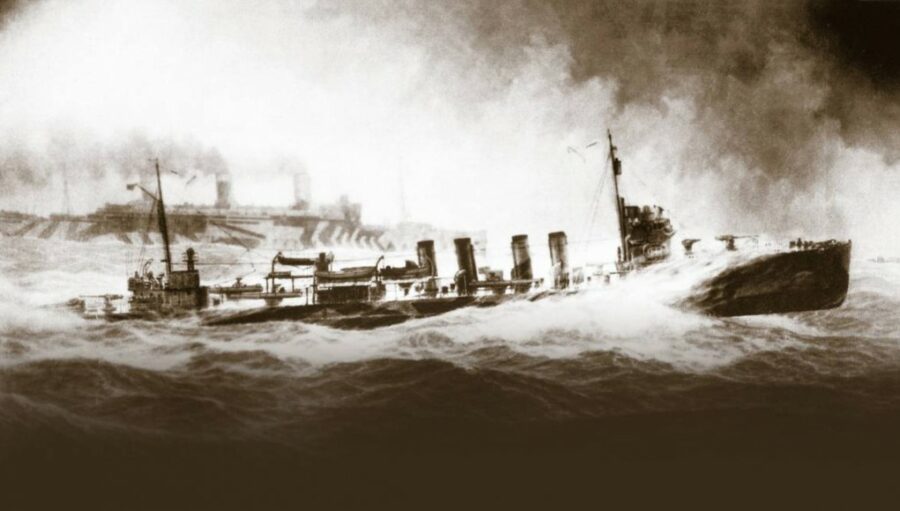

In the early part of World War One, military technology was advancing but not on a broad front. Huge warships had huge power – 25 knots was fairly standard – but no radar or, for that matter, any recognition devices beyond eyesight, binoculars and telescopes. With wireless barely arrived, the fog of war inevitably produced incidents of what would, in later wars, be embraced by that PR-generated, placatory, blame-fudging term – friendly fire. Throw in that other, literal, fog for which the North Sea is known, and warships were sometimes as much a danger to themselves as the enemy. Friendly collisions accounted for several ships.

All of which helped bring mines and, still primitive, submarines to the fore, as more efficient weapons.

Submarines were relatively cheap, both to build and, with small crews, to man, even if they tended to take their whole crew with them if they sank. Submarines were deployed in rising numbers by the Germans in the aftermath of the first sea battle, Heligoland, on 28 August, 1914. The British victory there, in which three German light cruisers and a destroyer were sunk, put the wind up the Kaiser so much that he decreed that the German fleet should thenceforth ‘hold itself back and avoid actions which can lead to greater losses’, much to the outrage of his commanders.

During that fight, the brand new British light cruiser, HMS Arethusa, deployed before it could test its guns, engaged the German light cruiser, Frauenlob, with considerable mutual damage before the latter retreated. One casualty was the Arethusa’s cook who was preparing breakfast when his arm was shot off, and he would have bled to death, had he not found an empty cigarette tin and clapped it on the stump; a rare example of smoking saving a life.

The North Sea was thus very quickly full of mines and cruising U-boats, the latter soon targeting fishing boats in order to disrupt food supplies. Initially, U-boat skippers did the half-decent thing, surfacing nearby and ordering fishing crews to get into their lifeboat, sinking the trawler or drifter with gunfire or explosives rather than waste a torpedo. But this led to a British counter-ruse known as the Tethered Goat whereby a trawler would tow a submerged submarine, the tow hawser looking like a trawl tow, and when a U-boat appeared, the towing skipper would use a telephone wire down the hawser to tell his submarine, which would then have the advantage of surprise.

The ‘goat’ was usually an older B – or C-class submarine which were primitive machines – petrol-driven, highly incendiary, and filled with fumes from engine and gassing batteries – and already superseded by the diesel-powered D-class, and the particularly successful E-class, the latter two at least having a proper toilet, which was more than could be said for the others. (But then submariners did get paid more.)

The first success came on 23 June 1915, when the trawler Taranaki, A445, towing the submerged submarine C24 behind it, encountered U40 off Aberdeen, which C24 duly sank. A month later, on 20 July, C27 – towed by HMT Princess Louise H140 – sank U23 in the Fair Isle Channel.

The trawler Malta GY325 worked with C33 although, after slipping her tow on August 5 to return to harbour, the submarine disappeared with 17 crew; probably the victim of a mine. The Malta herself was mined off the North Shipwash buoy on 1 September. On 29 August, the trawler Ariadne GY173 was towing the submerged C29 when the submarine blew up, the pair of them having strayed into the German minefield off the Outer Dowsing Lightship. However, it didn’t take long for the Germans to get wise and start shelling fishing boats from a distance, whether or not the crew had got clear.

One eventual victim was Thomas Crisp who, nearing 40 and too old for military service, had returned to fishing after the initial disruption of the declaration, only for his boat, the George Borrow, to be sunk during 1915, although Crisp survived.

Thomas Crisp was then recruited to the Royal Naval Reserve, and in 1916 was skippering an armed smack, I’ll Try. As a sailing boat, it couldn’t tether goats but was actually a Q-ship, one that regularly went fishing but was really out there to appear vulnerable and entice submarines into range of its hidden three-pounder. He had his son, Tom, among the crew.

On 1 February 1917, I’ll Try was out fishing with another armed smack, Boy Alfred, in the North Sea, when they were confronted by two submarines, each of which fired torpedoes – expensive overkill on the Germans’ part and they still missed – while the smacks scored hits with their guns. The U-boats submerged and were presumed sunk, although post-war German records showed that none were lost that day. Both skippers were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and £200.

In July, I’ll Try was renamed Nelson, and Boy Alfred became Ethel & Millie, to maintain cover. On the 15 August, they were out fishing together, pulling in a catch during the morning before separating to make sweeps for submarines near the Jim Howe Bank. At 2.30pm, Thomas Crisp spotted a surfaced U-boat at 6,000 yards, probably U63, that began firing its 88mm deck gun at once, from well beyond the Nelson’s gun’s range, scoring several hits.

The fourth shot holed the smack, and the seventh tore off both of Crisp’s legs from beneath him. Calling for the confidential papers to be thrown overboard, he dictated a message to be sent by the boat’s four carrier pigeons, because the Nelson had no radio.

“Nelson being attacked by submarine. Skipper killed. Jim Howe Bank. Send assistance at once.”

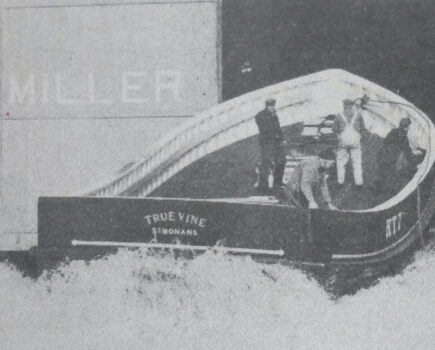

The boat was abandoned by the nine unwounded crew – Thomas Crisp had ordered that he be thrown overboard, but went down with his ship – at which point the Ethel & Millie arrived, coming under fire and also beginning to sink. Her crew was then hauled aboard the submarine, where the Nelson survivors last saw them standing in line being addressed by a German officer. They were never seen again.

The Nelson survivors drifted for nearly two days until they arrived at the Jim Howe Buoy, where they were rescued by a fishery protection vessel, Dryad, sent out after one pigeon reached Lowestoft.

Thomas Crisp was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross, while his son and another crew member each received Distinguished Service Medals.

We’ll have more from John Worrall on fishermen in WWI very soon. Head to our news page for more from Fishing News.