Greg Asbed, from the US-based Coalition of Immokalee Workers, visited the UK as part of a delegation to meet fishing industry representatives interested in learning from the successful Fair Food Programme. Under the scheme, retailers provide significant benefits to responsible farmers – who do not pay to participate – driving major improvements for their workforces. Here he reports on his experiences

In late September, I was part of a team from the Florida-based Fair Food Programme (FFP) who visited the UK to hear from fishermen and vessel owners and a wide variety of others about the crewing and welfare situation in the UK fishing industry.

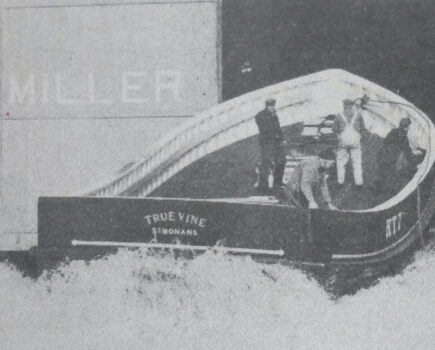

The visiting team in Peterhead. Left to right, Chris Williams of the ITF, Greg Asbed, Marley Monacello and Cruz Salucio of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW), Paul Shulman of the Fair Food Standards Council and Lucas Benitez of the CIW.

Our hosts, the International Transport Workers’ Federation, organised meetings with the fishing industry across UK ports to discuss ways in which fishing vessel owners could possibly adapt our work in Florida to the fishing industry context, and see if this could help address the increasingly high-profile issues relating to crew welfare in certain sectors of the UK fishing industry.

The level of agreement on fundamental issues that we encountered across the course of our stay was nothing short of remarkable. While there may be some disagreement on how widespread labour abuse is in the industry, no one dismisses its existence altogether, and everyone agrees that something – and, importantly, something new – must be done. On that point, all agree.

The Fair Food Programme logo can be seen on certified produce in US grocery stores like Whole Foods Market. In the USA the scheme includes a premium

that buyers pay to fund a bonus for workers on top of their regular wages, and the cost of certification is not borne by the farmers themselves.

All agree as well that workers lack a meaningful voice in the industry, a problem that has grown as the number of foreign crew has increased in the fleet. We found a strong consensus around the idea that any human rights initiative must include real consequences for those employers who fail to comply with its standards if it is to have any hope of success in the fishing industry.

Stakeholders of all stripes told us that without significant consequences – in combination with meaningful rewards for those who treat their workers well – those employers who oppose real change won’t take the programme seriously, while those who are inclined toward progress will soon lose any incentive to comply when they see that they are playing on an uneven pitch.

Fortunately, those last key points of agreement – on the need for workers to have a real voice in the industry, and the need for any successful programme to have meaningful consequences for violations, together with market benefits for compliance – are the fundamental pillars of the FFP.

Born nearly 20 years ago in the tomato fields of Florida, and expanded now to multiple new crops and new states across the US, the FFP grew out of the efforts of the farmworker community of Immokalee, Florida, who in the early 1990s began organising for what they called ‘a more modern, more humane food industry’. The workers had grown tired of generations of farm labour poverty and abuse – exploitation so extreme that federal prosecutors from the Department of Justice dubbed Florida ‘ground zero for modern-day slavery’ in 2003.

In 2001, farmworkers with the Coalition of Immokalee Workers launched the Campaign for Fair Food, joining with consumers in calling on massive retail food brands like McDonald’s, Sodexo and Walmart to take responsibility for the labour conditions in their supply chains.

Tough hours and working conditions, but a pride in the job and the food produced: possibly there is more in common between farmworkers and fishermen than people think!

The basic idea was quite simple: reward growers who do the right thing by buying their produce, and don’t buy from those who don’t. By 2010, nearly a dozen major food chains had signed innovative, legally binding agreements with the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, committing, among other things, to only buy Florida tomatoes from growers who join the FFP.

The FFP was inaugurated in 2011 on over 90% of Florida tomato farms, and its impact was immediate. Just three years later, the Florida tomato industry was hailed as ‘the best workplace environment in US agriculture’ on the front page of the New York Times.

That 180° reversal of reputation is reflected today in measurable results in the fields. Farmworkers in the FFP today work free of the worst abuses that plagued US agriculture for decades, including forced labour, sexual assault and violence – and when wage and health and safety issues do arise, workers can make complaints without fear of losing their jobs.

The transformation of the agricultural industry brought about by the FFP has caught the attention of human rights observers from the White House to the United Nations. Amongst other accolades, in 2015 the FFP received a Presidential Medal from the Obama-Biden administration for its ‘extraordinary efforts to combat human trafficking’.

Which brings us back to the great commercial fishing ports of Scotland and Northern Ireland, where we found near universal agreement on one more important point during our conversations last month: a programme like the FFP, with a strong leadership role for workers and clear market consequences for employers who refuse to meet basic labour standards on their vessels, might just make sense for the UK fishing industry.

Perhaps it shouldn’t be such a surprise that a model born in the withering heat of tomato fields in America might present a solution to labour problems on UK fishing vessels working miles from UK coastlines. After all, the two industries may be more alike than they are different. Vessel owners, like farmers, talk of ‘harvesting’ the seabed for the precious prawns they land at ports like Fraserburgh or Kilkeel, and rotate their harvests to protect the sustainability of production. Fishermen, like farmworkers, speak with an identical and hard-earned pride of the dangerous and back-breaking work they do.

Even with all the encouraging similarities and agreement, however, there remains a long road ahead before a ‘Fair Fish Programme’ pilot can be launched – a road that will demand compromise and commitment from a famously independent industry (reminding us of yet another similarity with US agriculture). But we’ll never know until we try. Plans are underway for a visit by foreign fishermen’s representatives and UK vessel owners to Florida in the coming months.

We were immensely impressed with the open minds and vision of the Scottish White Fish Producers’ Association and the POs that we met. Rather than close ranks and turn a blind eye to concerns raised by those outside the industry, they have fully engaged and quickly realised the benefits to the fishing industry from embracing the challenges of creating a bespoke, UK fishing industry scheme.

We look forward to helping them to meet that challenge, in any way we can.

This story was taken from the latest issue of Fishing News. For more up-to-date and in-depth reports on the UK and Irish commercial fishing sector, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.30 here.