Joseph Kay, who spent the majority of his career as a fisherman, latterly as second skipper on the Donvale, shares memories of Shetland’s restored sailing Fifie Swan, and stories from those who crewed the Swan and similar vessels in their fishing days

In Shetland we have much to count our blessings for. Our location may be to our disadvantage regarding travel and freight, but as we have seen during the recent pandemic, there are definite advantages in living where we do.

Swan LK 243 following her relaunch as a sail training vessel.

In spite of the havoc wrought on the fishing industry over recent decades, those who remain are enjoying earnings previously unimaginable or undreamt of, and those who were displaced from the industry have mainly found work in the oil and aquaculture industries.

However, there are some who are suffering as a result of the Covid crisis. Hotels, bars and all involved in the hospitality and travel industries are among those affected – including the Swan, which has been tied up over the past year.

The restoration and running of the Swan has been a big commitment and great achievement for Shetland. At the time of her restoration, there was divided opinion, as there is with many projects. In spite of that, it was seen through to fruition, and she is now a great Shetland ambassador and sail training vessel.

Having been involved in the Swan project – I should say in small part – and as someone with an interest in maritime and fishing history, it was suggested I comment on her history. The Swan tells the story of the changes that took place in Shetland, and in many fishing communities throughout the UK, during the first half of the 20th century.

JR Nicholson recounts the history of The Swan in his book of that name. It gives an insight into the changes that took place on Whalsay from the Zulus and the Fifies to the replacement purpose-built diesel-powered seiner-drifters of the 1950s. The following few notes have been recorded or handed down, and may add a little more to the Swan’s history.

Swan during her fishing days.

Built in 1900 as a sailing lugger for Thomas Isbister of Lerwick, she was reported in the press at the time to be one of the finest boats in the Scottish fleet. However, when sold to Whalsay in 1905, her hull and rig already belonged to the past, with modern steam drifters being built and operating successfully.

In spite of the modern advances, no steam drifters were ever built for Whalsay – but sailing vessels such as the Swan offered a better opportunity for the fishermen there. Previously, those fishermen were faced with making a living at the haaf fishing in small open boats, crewing on whalers, or taking part in the Faroe fishing, all of which were precarious, with considerable loss of life. The larger-decked herring boats proved a far safer form of fishing than anything that had gone before. The half-deckers and lang boomers preceded the Swan type in Shetland, and it was probably on the strength of their success that fishermen were able to purchase the larger-decked boats.

During the 1910 herring season, the Swan grossed £455, with the Children’s Trust and the Research being the only two Whalsay boats bettering her, grossing £570 and £550 respectively (as recorded in the Shetland Times on 24 December, 1910). In 1911, the Swan was Whalsay’s top boat, with over £500; next were Guide Me and Research with close on £500 (Shetland Times, 21 October, 1911). The Guide Me was one of the afore-mentioned lang boomers, only 57ft, and would have probably been carrying fewer nets than either Research or Swan.

By 1913, Whalsay had a fleet of 12 large herring boats. That summer season, the Swan grossed £711, and was said to be Whalsay’s top boat. The earnings at Peterhead that year for sail boats was £350 to £1,000, with steam drifters approximately doubling this figure, according to the Aberdeen Daily Journal of 15 September, 1913. While those earnings seem small today, this got the crofter/fishing folk of Whalsay off the ground, from the earthen floor and thatched roof to more comfortable circumstances.

The 1930s saw the demise of the sailing drifter, and by 1937, the Gracie Brown was the last survivor. By then, all of the other old sailing drifters had been scrapped or motorised. It is an interesting fact that those motorised sail drifters were to see off the steam drifter – the last such converted sail boat being the Research II in the late 1960s. It is also interesting that in spite of Whalsay achieving a large foothold in the present-day pelagic fisheries, no steam drifter was ever owned in Whalsay.

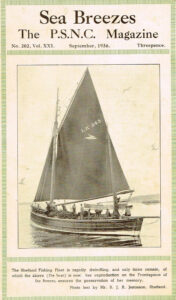

Swan pictured on the cover

of Sea Breezes magazine in September 1936. The caption beneath the photograph refers to sail boats. The 1930s were poor years for the herring fishing in general – by 1935, Whalsay was left with just seven large herring boats, a reduction from 30 at its peak.

Fishing memories

Being at the fishing with several men who were on the Swan in her motorised fishing days, I heard many stories from that time. No fortunes were made at the fishing back then, but such boats kept going and served to keep a thread of fishermen employed – and when the door of opportunity was opened during the 1950s, such fishermen were able to take advantage of the government loan and grant scheme and order new purpose-built boats. Those young men in fishing communities such as Whalsay and Burra Isle were the nucleus of our modern fishing industry.

The Swan under her Whalsay ownership spent her last few winters at the seine-net, and many nights were spent at moorings in Burravoe in Yell. On one occasion she was leaving Burravoe with a southeasterly gale, when to weather of Linna-holm, the engine stopped. The vessel was skippered by Bobby o’ Huxter – Bobby Polson Snr – on that trip.

The engineer/driver Davie Kay was in the wheelhouse with Bobby, and said: “I bet that’s the points! This magneto seems to be burning them. There are spare ones doon forrad. I will go ’n’ pit dem in – soodnoo taak lang!” (“There are spare ones below. I will go and put them in – it shouldn’t take long!”) Bobby replied in his characteristic unruffled manner: “Yes, do dat – taak dye time. Dunoo slip ony o’ yun peerie screws ida bilges. It will taak a start afore we drive ashore in Linna-holm.” (“Yes, do that – take your time. Don’t drop any of those little screws in the bilges. It will be a while before we ground on Linna-holm.”)

Bobby normally skippered the Research where they had the luxury of two engines, which was more dependable – if only by the fact that at least one would be expected to keep going.

Mention of Bobby o’ Huxter brings another story to mind. After the Swan’s restoration, she made a trial trip to Whalsay one fine Sunday, with a perfect sunny sailing breeze. Among the men who took a run from Symbister was Mackie Polson, skipper of the Serene and Bobby’s son.

He relayed a story told by his father of the first Research – a Fifie similar to the Swan. They had been out from the Ramna Stacks, and were faced with having to tack for Yell Sound with a light contrary wind. Bobby and one of the crew had been left in charge, both teenagers, with the remaining crew having turned in. On approaching the stacks, they stood on as near as they dared before tacking; however, in so doing, she mis-stayed, only managing to come to the wind before losing headway, with the sails in irons.

Before they could do anything, she began making stern board, and in an instant the rudder brought her up on the rock – but luckily she fell off on the right tack and saved the situation. None of the crew below were aware of any of this, and if any heard anything, they probably just thought it was the normal commotion in coming about.

This incident was kept secret by Bobby and his watch-mate for many years after the event. Mackie was in his element that afternoon, and told many other stories. He also crewed on the Swan on occasion.

Working under sail alone in such craft required a thorough knowledge of the shoreline. When faced with tacking through the many sounds around Shetland, they had to take advantage of all navigable water. On one occasion, when the Swan was making her way from the herring south through Whalsay Sound under sail, skipper John Simpson and his brother Robbie were on deck when they spied a local man, Thomas Henderson, at the craigs at the head of Brough. One said to the other: “Haad her up for daa heed. I will geen ’n’ string up a half o’ dozen o’ herring ’n’ fire dem ti him.” (“Make for the head. I will go and string up half a dozen herring and throw them to him.”) This they did as they made their way south through the sound.

Swan in 1997, following her restoration.

The Swan also met with an accident one morning in June 1908 while making for Yell Sound. The Shetland Times of 27 June, 1908 recounts: “The Swan had hauled her nets and was running for port (North Roe) when her foremast snapped right off… Fortunately no one was injured… The Swan managed to run in under her own canvas to the entrance to the harbour, when she got assistance from the boat Dauntless. There a jury mast was rigged up, and the Swan left for Lerwick for repairs… Between Whalsay and Lerwick the Swan got assistance from the boat Research of Whalsay.”

In Whalsay, boats such as Swan were remembered as working fishing boats – converted sail-boats that were far from ideal for their new roles as motorised seiner-drifters. Many men who manned such boats knew too well the discomfort and awkwardness of working them, and believed they had hung on to the past too long, simply because real opportunity did not present itself until the 1950s.

My father Davie Kay told of the difference of starting the old 75 paraffin Gardner on a cold morning, where the first step was to light up two paraffin blowlamps to warm the engine. Then came the physically demanding job of turning it over by hand until it started – whereas on the modern replacement boat, it took only the push of a button to start the modern Gardner diesel.

He also told of joining the Swan as cook and coiler, where like most in that chamber of horrors, the ‘rope hole’, he was bothered with seasickness. This not being misery enough, many of the old hands smoked black twist tobacco in a pipe. The rope hole was maybe handy for the steam boiler – anyhow, matches were kept in there, and the boy-coiler’s secondary role was that of lighting up those pipes, one after another, which were frequently extinguished on deck.

However, few on Whalsay, or anywhere else, would disagree in wishing the Swan and all who sail in her all the best, and in hoping she finds her way back to sea as soon as possible.