Exactly 85 years ago, swashbuckling Scottish skipper Dod Orsborne made a massive April Fool of his bosses when he stole the Grimsby seine-netter Girl Pat and sailed her into an 80-day, 5,000-mile chase that made him a worldwide celebrity. Brian W Lavery reports

If Dod Orsborne had not existed, Hollywood would have created him.

He went from child to gung-ho adventurer when, aged just 14, he joined the Royal Navy during the First World War, having lied about his age. “I did not really have an adolescence,” he recalled many years later in one of his memoirs.

Depending on which version of those memoirs you believe, he was born, on 4 July, in 1902, 1903 or 1904, in the Aberdeenshire town of Buckie.

At the age when most kids would be stamp-collecting, Orsborne was at war. He served in the Dover Patrol and was wounded in the Zeebrugge Raid, the disastrous bid on St George’s Day 1918 by the British to block the Brugge canal to try to stop German U-boat patrols.

The adventurous junior Scot left the Senior Service in 1919, and worked ashore briefly before the first of many movie-script moments of his life, when by chance he met a former captain of the Cutty Sark, who persuaded him to join the merchant navy.

He spent a few years sailing on small vessels from Liverpool, before moving to Grimsby. In Liverpool he left a broken-hearted shipping boss’ grand-daughter, whom the old man sent abroad – but not before paying Orsborne to leave her alone.

He passed his skipper’s ticket aged 21, after just three months’ study, and took command of a Grimsby trawler.

The Girl Pat detained in Georgetown, after 5,000 miles and 80 days.

For the next decade, Orsborne recalled that he ‘did a bit of everything’. This included fishing, Arctic whaling, a spot of rum-running and some spying and sabotage!

He also managed to fit in an unsuccessful expedition to Brazil in 1927 to try to find wreckage of a monoplane piloted by American adventurer Paul Redfern, who had flown from the state of Georgia to try to break Charles Lindberg’s non-stop flight record.

In 1936, Orsborne joined the trawler firm Marstrand’s of Grimsby.

In late March that year, he tried to get mate Alexander Maclean of his then-command Gypsy Love – a seine-netter – to join him in taking her for ‘an Atlantic adventure’.

Maclean declined what he saw as a hare-brained scheme – but it was of no matter, because the Gypsy Love had to return to port with engine trouble.

Dod Orsborne was then given command of the Girl Pat GY 176, and with his bosses’ permission transferred the stores and crew to the 66ft, 50t vessel.

He replaced Maclean with local sailor Harry Stone, who had no mate’s ticket. They were joined by Yorkshireman Hector Harris and teenage Scottish cook Howard Stephen, better known as Bill Stephen, who had the nickname Ginger. Regular engineer George Jefferson was retained. Dod’s brother Jim, also a teenager at the time, stowed away until they were at sea.

On 1 April, the fishing boat left Grimsby and began an 80-day maritime game of cat and mouse that would have the world’s media watching, as a public desperate for the next episode in this real-life high-seas soap opera cheered them on.

Ostensibly, the Girl Pat had set off on a 14-day fishing trip in the North Sea. But hours out, Orsborne gathered all the men, bar engineer Jefferson, in the wheelhouse, where the charismatic skipper’s oratory convinced them to join him on an Atlantic voyage. There was talk of pearl fishing and fortunes to be made.

According to later reports, as the vessel headed for Dover, the crew were spellbound by tales of treasure and dreams of what they would spend their ill-gotten gains on.

The four men whose trans- Atlantic voyage made headlines. Left to right: skipper Dod Orsborne and crew members Howard (Bill) Stephen, Hector Harris and James (Jim) Orsborne, brother of Dod.

The men must have had an unswerving loyalty to their persuasive skipper, especially when he told them that not only did the ship have no charts, but also that their proposed 5,000-mile odyssey would be conducted with only a sixpenny atlas – a schoolboy’s book that he had taken from his 11-year-old son Jim’s pocket before he left Grimsby.

Once in Dover, they loaded up with more supplies and headed south, leaving behind a drunk and unconscious engineer. George Jefferson’s bender ended with him getting back to the dockside to realise his ship had gone.

For the next few weeks there was no sign of the Girl Pat. It was as if she had dropped off the earth.

In reality, Dod Orsborne and the crew were off the coast of Jersey, awaiting calmer weather before heading for the Bay of Biscay. But the little ship then took a battering and was forced back to seek shelter in the Spanish port of Corcubión, where they remained for around a fortnight.

Orsborne ordered a full load of fresh supplies and had repairs carried out. He even billed Marstrand’s of Grimsby for the £235 it cost.

The Girl Pat was treated to a repaint and had her Grimsby name and number covered over. She was renamed the Kia-ora.

When the confused engineer Jefferson arrived back in Grimsby, the owners thought at first that Orsborne had replaced him and decided to fish in the south – but they soon realised otherwise. They then assumed the Girl Pat was lost – and got a £2,400 pay-out from Lloyd’s of London for the year-old vessel.

But then, a bill for supplies arrived from a Spanish port, along with a report that the Girl Pat was sailing south. A Lloyd’s of London investigator was dispatched.

Meanwhile, the Girl Pat continued south, hugging the African coast. The crew went ashore at French West Africa (now Mauritania), where their unguarded vessel was robbed, and put back to sea with much-reduced rations.

On 17 May, a British ocean liner reported a small vessel matching the missing seine-netter’s description. The SS Avoceta noted the craft near an uninhabited archipelago 150 or so miles from Madeira – an area associated with pirates and rumoured treasure.

It wasn’t long before the world’s newswires were buzzing, as they filled in the gaps with tales of derring-do. The swashbuckling Scottish skipper now became a latter-day Captain Kidd hunting treasure – and reports sprang up across the world of this band of buccaneers and their high-seas hi-jinks.

In truth, the likelihood was that Orsborne intended to sell the vessel to an unscrupulous dealer in South America. If the trawler firm bosses had known his background, they might not have been so quick to hire him. It was later revealed that he had a shady few years before arriving in Grimsby – he had been commander of an intelligence-gathering Q-ship in the Mediterranean, and was involved in sabotaging aircraft supplies from fascist Germany destined for its allies within France and Franco’s forces in Spain.

The Girl Pat’s fame led to the production of postcards commemorating the chase.

By 23 May, the Girl Pat’s crew were down to their last four bottles of water, some corned beef and some condensed milk when they hit a sandbank. They were stranded for three days before they got her refloated. By then, the exhausted men were happy to be picked up by a pilot boat and taken to Dakar.

Harry Stone fell ill and was taken to hospital there. It was later found to be appendicitis.

The arrival of the vessel attracted the interest of the local Lloyd’s agent. It looked like the game was up.

International press interest was booming now, and reports of the brave little ship and her gung-ho crew and gallant captain were wired around the globe. UK film-maker Gaumont British announced it would make a movie of the epic voyage of the Girl Pat.

But Orsborne had one more trick up his sleeve. The Lloyd’s agent noted that the skipper had altered the ship’s log. In it he was listed as George Black, his brother as A Black and the stricken Stone as H Clark. (Black was Orsborne’s real name. It was changed in childhood when his stepfather moved the family from Buckie.)

Three days later, Orsborne was commanded to take the real ship’s papers to the British Consulate – which he promised to do after ‘testing the engines’. The Girl Pat disappeared once again. The British Foreign Office then gave an order for the vessel to be detained on sight.

On 2 June, a French liner reported a vessel resembling the Girl Pat going south from Dakar. But a week later, an American ship cabled Lloyd’s agents in Georgetown, British Guyana saying it had seen a small ship flying a distress signal off that coast.

There were apparently four men onboard. The vessel’s markings were blanked out, but she claimed to be the ‘Margaret Harold’, bound for Trinidad from London. Lloyd’s confirmed there was no registered ship of that name.

The US ship’s captain thought the crew’s behaviour suspicious, and when he asked to see papers, the vessel lowered her distress signal and sped off.

Next day, a report from the Îles du Salut, off French Guyana, said a vessel similar in appearance to the Girl Pat had watered there, but a 1,000-mile air search around Georgetown revealed nothing.

The hunt came to a shocking halt when the vessel was reported lost with all hands on 17 June. There were many press reports of the wreck of a small boat and three bodies found at Atwood Cay Island in the Bahamas.

Orsborne’s skipper’s ticket, which he earned aged just 21.

Once again, the press leapt to get two and two to make five – one headline read: ‘Did School Atlas Course Lead Crew to Death?’

But reports of the demise of the Girl Pat were short-lived. In the early hours of 19 June, a police launch towed her into Georgetown harbour.

The night before, an unarmed police boat had responded to a report of the seine-netter being sighted. When they came alongside, the crewmen became hostile. The police backed off, only to return hours later – this time fully armed.

The Girl Pat was pursued for two hours before surrendering to the Georgetown police. The defeated crew were towed to port. This time there was no escape plan. Skipper Orsborne and his crew were under police guard.

It was later revealed, however, that a Georgetown solicitor representing Orsborne and his crew did a deal with a press agency for £5,000 for the rights to the story, with £200 on account, making their time waiting for extradition that bit easier.

While the world’s press regaled its readers with tales of derring-do, Orsborne’s hometown paper revealed the sadder side of the story. The Grimsby Telegraph reported from the Orsborne family home, where wife Ina had been abandoned with her 10 children and forced to appeal to the ‘parish’ for food.

Photographed in what looked like Dickensian conditions, Orsborne’s put-upon wife told the paper: “I have got no reason why he should leave the children and myself unprovided for, as he always seemed fond of them.

“But he’s always been on the bold and reckless side, adventuresome and eager for change and excitement.”

In October 1936, the press gallery of London’s Old Bailey was packed for the crew’s trial. Dod Orsborne was the star of the show – and he knew it. His defence was that Marstrand’s managing director John Moore had asked him to sink the vessel for the insurance, in return for a 15% cut – which Moore said was ‘preposterous’.

Skipper Orsborne took the stand, aware of the eyes of the press on him. He said, to laughter, that, having decided not to go ahead with Moore’s alleged plan: “I suggested to the crew that we may as well make a holiday of it.

“I said we should make a circle of the Atlantic Ocean before returning the boat, and thank the owners for the loan of the ship.”

He told the court he left Jefferson in Dover because ‘he was a poor mechanic and a drunk’.

The crew’s defence collapsed under cross-examination – and the vessel owners proved there was no financial pressure on the trawler firm, as Orsborne had claimed. Dod Orsborne was sentenced to 18 months’ hard labour, and his brother to a year.

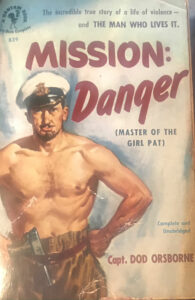

The cover of one of Dod Orsborne’s adventure memoirs. (Photo: Phil Orsborne)

In spite of the verdict, the media still lionised Dod Orsborne. A leader article in the Times said: “It is difficult not to entertain a sneaking gratitude towards the two men whose curious and unsuccessful adventure has sent us all vicariously sailing on a desperate mission across tropic seas.

“Apart from the length of their voyage and their happy-go-lucky methods, they maintained to the end an air that was at once tough and enigmatic.”

Orsborne went on to a life of further adventure. He wrote or helped to write five books from 1937 onwards, published in several languages.

In 1951, he was in the headlines again, allegedly gun-running off the coast of Trinidad.

In his later books, he claimed the Girl Pat escapade was a British intelligence cover for a mission spying on Spanish fascists. He courted publicity and continued enhancing his image as a real-life matinee idol.

George Black Orsborne died in 1957 of a heart attack in a Brittany hotel room. Back in Grimsby, Ina, the wife who stood by him for all his faults, outlived him by nearly 30 years, dying in 1986 aged 87.

Dod Orsborne was undoubtedly a brave and heroic man. He was also, by his own admissions, a superlative self-publicist, adventurer, narcissist and serial adulterer, well aware of what today’s celebrities would call their ‘brand’.

Many doubts remain over aspects of his versions of his life story. The British government still holds files on the former master of the Girl Pat. They are set to be made public in 2038. n

Pictures courtesy of the Grimsby Telegraph and Phil Orsborne.