The whelk Fisheries Management Plan (FMP) is the last of the six FMPs that are currently out to consultation, with a deadline for responses of 1 October.

We’ve taken a robust view on the need for the industry to engage with these consultations. Whatever your views on the management of the fisheries concerned, FMPs are a legal requirement and are here to stay. And in many respects, as with the flawed roll-out of iVMS, English fishermen, and in particular, the English inshore fleet, are the ‘canary in the coalmine’.

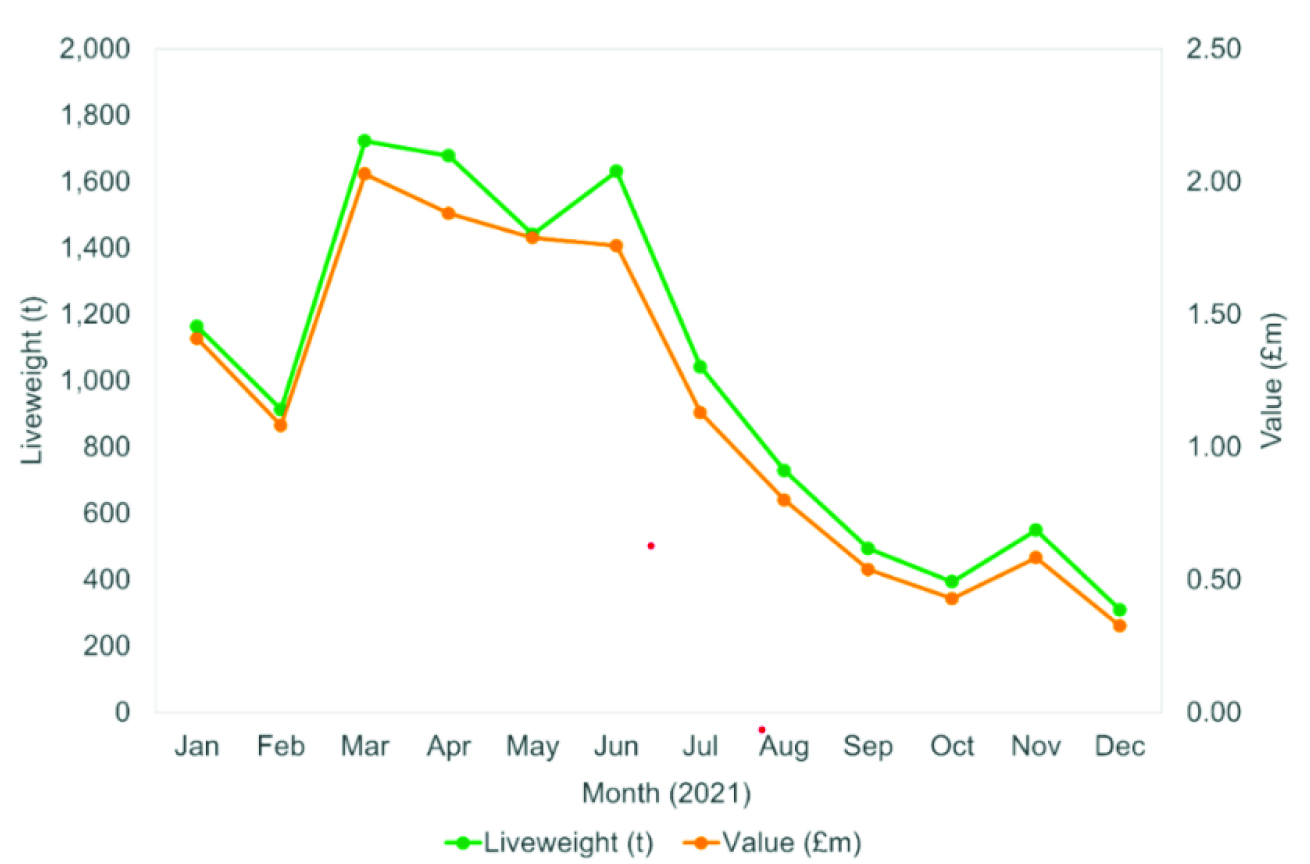

Monthly landings and value of whelks in English waters in 2021. Whelks need cold temperatures to trigger their spawning, which tends to take place from November to January. A seasonal closure to assist successful spawning, the figures suggest, would have a relatively small impact on earnings of the fleet. Fishermen also pointed out during the development of the FMP that the meat yields from whelks getting ready to spawn, or recently spawned, was very poor, further reducing the value of catches in the winter months.

With FMPs due to be introduced across the UK in the coming years, Defra has recognised that a one-size-fits-all approach may not be the best one, and no doubt will learn from the success, or otherwise, of the very different approaches taken to the initial six FMPs, and their eventual approval.

An early indication is that those FMPs with early, and extensive, fishing industry involvement are much more realistic, and more likely to meet their objectives, than those where the industry has been less centrally involved.

As many commentators have written over the summer, you don’t need to read several hundred pages of detailed jargon, much of it incomprehensible to the man in the street, and in any case largely irrelevant to basic questions about how best to manage our fisheries. Each of the six FMPs has a simple online response form, where you can say as little, or as much, as you want.

Loading whelks in Wells-next-the-Sea in Norfolk: like many ports around England where whelks are a vital part of incomes, the bulk of landings here come from the under-10m fleet.

However much you do or don’t say, we would urge you to make your voice heard. NGOs, anglers and militant anti-fishing groups are all sure to make their views all too clear. We trust that you will too.

The Whelk FMP, as with the Scallop and Crab and Lobster FMPs, is the result of the fishing industry itself pushing for management of a stock that over the last 20 years has become a lifeline for many ports and inshore fleets. Developed with support from Seafish, this FMP is the outcome of a number of workshops and open meetings around English ports, with active participation of working fishermen, many of whom brought decades of practical experience to the discussions.

Once a niche fishery for local markets, UK whelk landings increased steadily from the late 1990s, when the Korean market took off, reaching 8,687t in 2002 and 16,000t in 2012. 2021 landings were recorded at 19,400t, worth £22.4m, with Korea still the main market, but with an increasing share of exports of live whelks going to France.

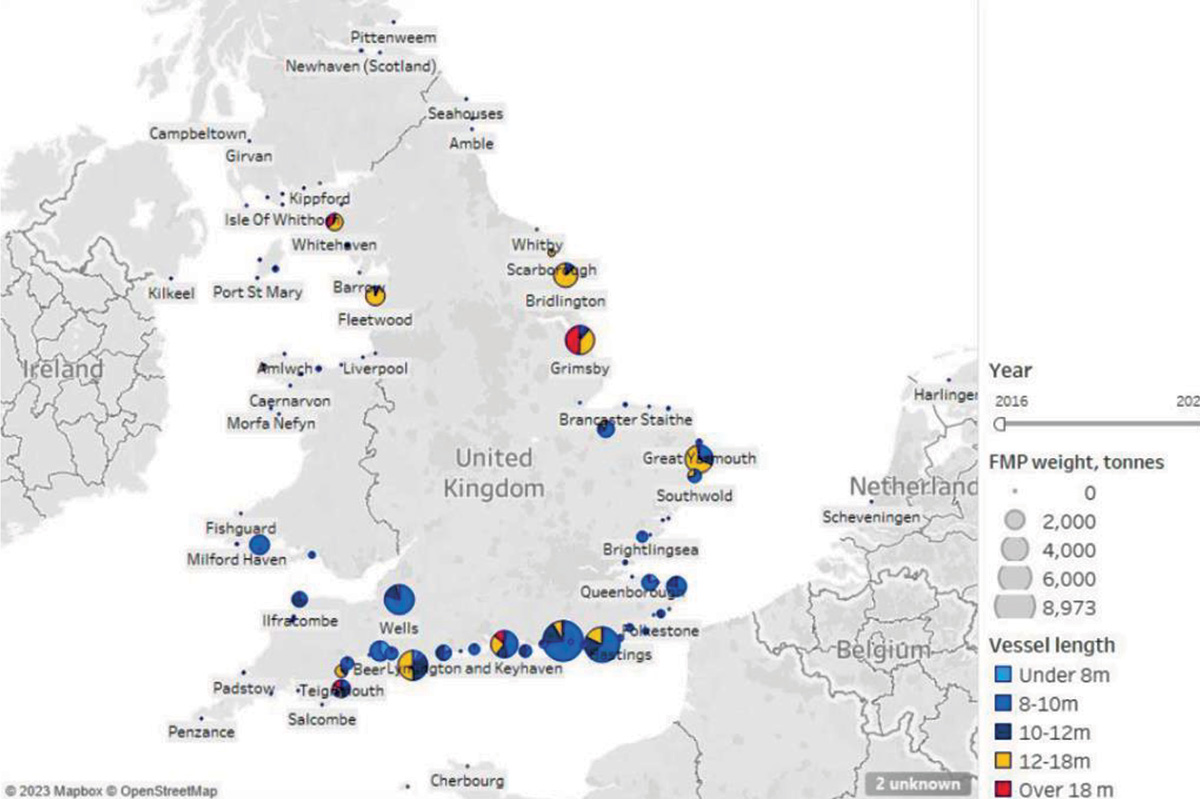

Whelks are landed across the English and Irish coasts, but it is the Eastern Channel, dominated by under-10m vessels, where landings are concentrated

Although there are larger vessels working offshore and undertaking multi-day trips, it is day-boats, and the under- 10m fleet, that continue to take the majority of the whelk landed into the UK. Shoreham is the most valuable port, with recorded landings of 1,700t in 2021, worth over £2m.

Vessels fishing primarily for whelks in 2020 made up nearly 7% of active vessels in England, more than double their percentage share of the English fleet in 2009, underlining the growing importance of the species to the English fleet, with almost exactly half of landings being taken by the under-10m sector.

Slow-growing, producing relatively small numbers of offspring, and covering the seabed at, in fact, a snail’s pace, the stock is a strange one for scientists and fishermen to try to manage to the maximum sustainable yield enshrined in legislation.

The FMP also recognises the relatively poor data available on the fishery. Few boats have provided records of the number of pots in use, so landings per unit effort – a good indicator in some fisheries of the state of a stock – can’t be calculated.

The FMP instead suggests a number of ‘shellfish principles’ that should be the aim of all the shellfish FMPs. In reality, however, these are so general as to be close to meaningless – who doesn’t want a fishery to aim to be ‘sustainable’ or to ‘implement best practice handling measures’?

Whelk pots ashore in Paignton. For a lot of vessels, whelks are a vital seasonal fishery that reduces effort on crab, lobster and net fisheries. One key requirement for any Whelk FMP will be to allow vessels to move between fisheries, rather than become reliant on a single species.

The real gist of the FMP and the consultations comes with two suggestions: the introduction of whelk licences, and the potential for a seasonal closure.

The introduction of a specific whelk entitlement, the FMP suggests, would be not only a way of eventually capping the amount of effort in the fishery, through a limit on the number of vessels, but also a route for licence conditions that could include a cap on pot numbers per vessel, or specify escape panels, or even the sizes of pots to prevent unwanted ‘effort creep’ at some future stage. A desire to prevent a headlong rush of new entrants into the whelk fishery is understandable, but as with shellfish entitlements, bass entitlements and similar, every new measure to limit new entrants also sees more and more fishermen pigeonholed into a single fishery, without the traditional flexibility needed to cope with changing fisheries and markets.

The second key suggestion in the FMP is a possible seasonal closure. This is suggested to allow spawning to take place undisturbed, and allow as many eggs to be laid on the seabed as possible.

Fresh whelk for sale in France; after years of reliance on the Korean market, demand from France for fresh product has seen a growing proportion of UK landings exported there.

Given the nature of whelk spawning, and the relative ease of overfishing a local ground, compared to more mobile species, a seasonal closure may make sense, even if it coincides with the quietest fishing months of the year. However, many vessels – particularly offshore vessels that prefer to leave their gear on the grounds, even if only lifting it once a fortnight, while focusing on other fisheries – may not be too keen to bring gear ashore during the closed season.

And that is about the long and short of this FMP. Other suggestions – for improved data collection to enable accurate stock assessment and an understanding of catch per unit effort, and improved science

to get a better understanding of the stock boundaries – are longer-term objectives with little likelihood of impacting day to day activity in the fishery in the medium term.

Defra has made it very simple for those with an interest in the fishery to make their views known. There is a straightforward questionnaire online, with just 11 questions to answer. However, importantly, these questions don’t lock you into a yes/no answer, or limit what you can say by giving you some ‘options’ to tick, whether you like them or not.

The 11 questions include ample space for you to comment on the main management options for the fishery in the short term – introduction of whelk permits, and any possible licence conditions that come with these, a cap on whelk vessel numbers, and your thoughts on issues such as seasonal closures or raised MLS.

The consultation and supporting documents are available here.

The whelk experience elsewhere

Jersey

Don Thompson, chair of Jersey Fishermen’s Association, told FN about the island’s experience of working with a range of different local management measures. These have evolved over a number of years in a bid to maintain what is a vital local fishery.

“The whelk fishery around Jersey and throughout the broader Granville Bay Area is a very important one that supports a large number of vessels, merchants and processors, albeit since Brexit and the subsequent ban on direct landings into France by Jersey vessels, the main fleet is on the French side.

“The fishery is spread across both Jersey and French waters, with the effort in winter concentrated more

to the French coast and the summer fishery into the deeper, cooler Jersey waters. The fishery is MSC-certified by the French side, and is subject to some pretty rigorous sampling and ongoing data collection, both by Jersey and by SMEL on the French side.

“The principal control measure has been on effort. The use of permits to limit access and number of boats has been contentious.

“The restricted licences include a cap on pot numbers – 900 per boat on the Jersey fleet and around 700 on the French side. There is a common 70mm MLS, which hasn’t always sat well with industry. The Continental market for the largest whelks just doesn’t exist, and this is a real case of ‘top-down’ management that ignores the economic aspects of a fishery.

“There is also complete closure of the fishery during the main winter spawning season. Due to the nature of whelks and their method of reproduction, with no planktonic stage, there has always been a need to manage the fishery and the permits on a zonal basis. Recruitment can be slow when a specific area has been subject to excessive fishing pressure, as stocks tend to be extremely localised.

“Despite the relatively strong cross-border management and the reduction in boat and permit numbers over time, the general trend in the stocks has been a downward one.”

Wales

“FN spoke to two Welsh whelk fishermen, one of whom sits on the Whelk Management Group. Wales introduced its own legislation in 2021, which had broad support from Welsh whelk fishermen. It capped landings at 5,298t (the average landings recorded between 2015 and 2019) in a quota year that starts on 1 March, requires vessels to have a valid permit to land whelks, and caps monthly landings at 50t per vessel.

The landings ceiling has not yet been reached, but in theory, a seasonal closure will happen at the end of the quota year, which coincides with lowest fishing activity and the whelk spawning season.

One comment we received was: “We’re not yet seeing any reduction in effort from the big boys, working both inside and outside Welsh waters, and there is some concern that landings into Wales of whelk from outside the area may tip us over the tonnage cap, though it hasn’t happened yet.”

An alternative view was: “We are concerned that boats doing trips starting in Wales and landing into English ports are not sticking to the MLS inside [55mm, as opposed to 45mm outside the median line]. There is not a lot of enforcement at sea for this type of thing.”

Isle of Man

The Isle of Man has had a whelk licence cap in place for two decades, as well as a 75mm MLS, and pot limits inside three miles. The total pot limit is capped at 3,600, with a maximum of 1,000 pots per boat outside three miles.

David Beard, chief executive of the Manx Fish Producers’ Organisation, told FN: “Fisheries scientists, in order to help recruitment, advise that the MLS should be set at a size that allows the population to spawn once before it can be caught.

In this respect, the Isle of Man raised its MLS from 70mm to 75mm following scientific studies.

“The market generally prefers a smaller size, so this creates its own issues with marketing. Other fisheries, with lower MLS, can offer a wider range of end product, while Isle of Man-caught whelk can only be offered as medium to XL. But the fishery has to be managed with the size of maturity in mind – fishing below that level would require very strict effort controls to prevent potential stock collapse.

“The number of whelk permits are now strictly controlled in Isle of Man waters, plus there is a pot limit per permit. However, this does not automatically mean that we have a sustainable fishery, although we do know the maximum potential effort that can be applied to the fishery. There is still a requirement

for high-quality catch data to accurately assess the fishery going forward, and iVMS and associated reporting procedures should assist in this regard.”

This story was taken from the latest issue of Fishing News. For more up-to-date and in-depth reports on the UK and Irish commercial fishing sector, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.30 here.

Sign up to Fishing News’ FREE e-newsletter here.