Tom Watson, who skippered the Wyre Victory FD 181 during the second Cod War of 1972-3, recalls an encounter with an Icelandic gunboat in which Britain came out best

There has been a lot in the press of late linking the negotiations about the fishing limits when we leave the EU with the so-called Cod Wars with Iceland, when they extended their limits. This prompted me to reminisce about our experiences, and in particular when I disabled the gunboat Odinn.

Another notable retaliatory action by a UK trawler occurred in April 1976, when the Hull trawler Arctic Corsair H 320 rammed the gunboat Odinn, badly damaging its stern.

A fog buoy, as towed by merchant navy ships in Second World War convoys, was deployed as a decoy by the Wyre Victory. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

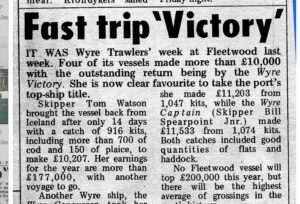

Wyre Victory was one of the most successful boats of her day, as reported in Fishing News in December 1971.

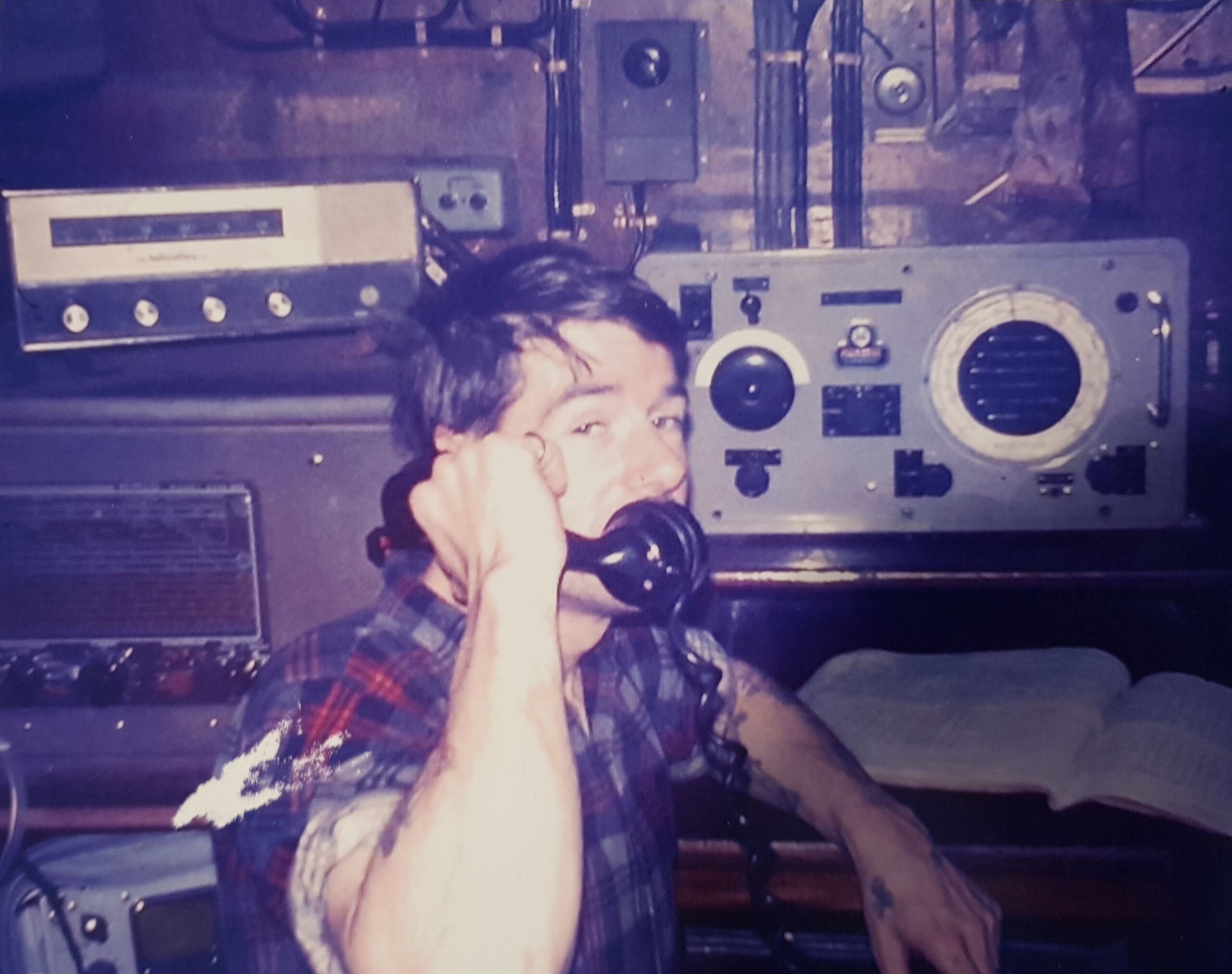

Skipper Tom Watson at around the time of this incident.

Wyre Victory FD 181. (Photo: Fleetwood Motor Trawlers/Mark Stopper)

Tom Watson

It occurred in April 1973, when we had a film crew onboard, filming the documentary ‘A Life Apart – Anxieties in a Trawling Community’, and the whole thing was filmed. That wasn’t intentional – I didn’t know that they had filmed it until it was all over, as I was too busy.

It occurred in April 1973, when we had a film crew onboard, filming the documentary ‘A Life Apart – Anxieties in a Trawling Community’, and the whole thing was filmed. That wasn’t intentional – I didn’t know that they had filmed it until it was all over, as I was too busy.

The disabling of Odinn was never shown in the documentary, and was kept out of the press because the government didn’t want to embarrass the Icelandic government during talks that were going on at that time – talks which, in fact, we now know were being heavily influenced by the trawler owners, but that’s another story.

Anyway, I’ll describe what happened; it is a long story because there were other characters involved who deserve a mention.

During our trip, we had had several run-ins with both the Odinn and the Aegir trying to cut our trawling gear away and, at one stage, Odinn had threatened us with its gun – nothing unusual in that; they threatened everybody.

The weather then freshened up so they left us alone for a bit, but once it moderated, the Odinn returned. We had by then moved grounds a bit further north across Ísafjörður gully and were enjoying a bit of peaceful fishing off Kogur and the Little Cape until he found us again.

He did the usual – called us on the VHF and warned us – but I had what I thought was a secret weapon.

Whilst in dock following the previous trip, the manager of Wyre Trawlers, Mike Johnstone, had suggested that it might be an idea to tow a device behind the vessel on a long tow-rope to try and dissuade them from going across the stern and cutting our gear. He suggested a device used by the merchant navy convoys during the Second World War called a fog buoy. This was a kind of small sledge that was towed behind the vessel during poor visibility and threw up a fountain of water that could be observed from the ship behind in the convoy, so it could keep on station.

We deployed this, and when Odinn came along, I gave them a good b——t story about how it was connected to our main generator and would send a powerful electric shock back up the cutting wire. The captain of the Odinn might have been a few things, but he wasn’t daft. He thanked me for the warning as he proceeded to turn alongside us to show the cutter being launched.

I then got the bosun, Cyril Armitage (his nickname was Spud – one of the best seamen I ever sailed with, apart from when he’d had his dram!), up onto the boat deck, where the grass rope attached to the fog buoy was made fast.

Odinn then turned and started its run and, as it approached, Spud began to release the grass rope. I ran out onto the boat deck shouting, “Not yet, not yet.” When the Odinn got to just short of crossing our stern, I shouted to Spud, “Now, Spud, let it go now!”

The timing was perfect! The heavy grass rope snaked out onto the surface, and Odinn crossed with a big bow wave that then dropped away, and became dead in the water. The rope had gone round its propellers and stripped them from the shaft; it was completely disabled and would have to be towed back to Reykjavík.

I hauled my gear and, after getting the gear onboard, called Odinn on the VHF and said that it looked like he had a problem, and could we help. I take my hat off to him because he answered me, even though his voice was trembling with rage. He told me no, I couldn’t help, but I should be aware that other Icelandic coastguard vessels were expected to arrive shortly, and wherever I went I would be arrested, and I would never be allowed to fish at Iceland again.

After that, I didn’t wait around too long. I started to steam along the North Side, and had a link call with the office to tell them what had happened. They said that they were disappointed because the orders were to ‘play it cool’, and when I said that they must be joking, even the operators at Portishead started laughing.

It was while steaming along the North Side that I got a 183-word telegram from somebody either in the government or MAFF, I forget which – but the telegram contained instructions of what I was supposed to do. I was instructed to immediately go outside the 50-mile limit and stay outside; I was to maintain radio silence and not communicate with anybody; I was to navigate around Iceland and down the East Side, keeping outside the 50-mile limit until I reached a set position off SE Iceland.

I was then to send just one telegram informing of when I would be docking. In reply – and this is the truth – I told the sparks to send back two words: “Get f—-d”. That is another thing I curse myself for, because I never saved that telegram.

Word must have got around, because we also got a call through Portishead radio for Michael Grigsby, the documentary producer onboard, from the ‘World in Action’ TV programme, asking what had happened. When they found out that it was all on film, they wanted to send a helicopter to get the film, but I wouldn’t give my position out because I was afraid that I would have been picked up by one of the other gunboats and arrested.

As I was steaming along the north coast, I picked up on a group of Hull and Grimsby boats that were on a ‘fish shop’ – an area where ships congregated when the fishing was good and plentiful.

Billy Hardy (‘Wiggy’, one of Grimsby’s top men) had picked it up and had a dhan down. (This was a marker buoy that was sometimes used when fishing was good, especially when there were no landmarks to fix the vessel’s position. It was a long piece of timber with a large cork fixture around it about halfway down, and had wire attached to an anchor which kept it fixed in one position. It also had a radar reflector fitted on the top, and was normally used when other means of fixing the ship’s geographical position were not available.)

I called one of the crew up on the VHF and asked what they were catching. I told them what had happened, but they already knew. They told me that they were on good fishing and invited us to join them. I said that they should be aware that I might bring the gunboat to them but, to a man, they were delighted with what had happened and said that if the gunboat came, we’d all chase it away.

We fished there for two or three days and I filled the boat up; we never saw a gunboat.

When I got home, I was told that I wasn’t to be allowed to go back to Iceland for three months, and I would have to go home fishing around the UK during a cooling-off period and, amazingly, I was requested to keep a low profile. I was not to speak to the press or TV about what had happened because, as mentioned before, sensitive negotiations with the Icelandic government were ongoing, and they didn’t want to cause any embarrassment. That is why this was never in the press or mentioned on the news. I never thought much about it at the time, but it makes me angry when I think about it now.

The Icelanders were offering a deal all the time, but our naïve and incompetent government was being lobbied by the greedy trawler owners to keep asking for more, and so we finished with nothing.

- The superb documentary ‘A Life Apart – Anxieties in a Trawling Community’, which intercuts footage of this Iceland trip with commentary from Fleetwood trawlermen and their families, is included in the British Film Institute free collection and can be seen in full at: bit.ly/3mppkyH

- Tom Watson is trying to locate the film of this incident, which he believes was removed from Granada Studios in Manchester by fisheries officials. If anyone has any information, please get in touch via: fishingnews.ed@kelsey.co.uk

Cod War 1972-3

The second Cod War between the UK and Iceland began in September 1972, when Iceland unilaterally extended its fishery limits to 50 nautical miles. British deep-sea trawlermen, who were heavily dependent on these rich fishing grounds, vehemently opposed the move and continued to fish inside the new limits. This set the stage for a year of confrontation between British trawlers and Icelandic fisheries patrol vessels.

This phase of the Cod Wars saw the Icelandic gunboats target the trawlers’ gear. The director of the Icelandic coastguard had invented the warp cutter or trawlwire cutter – a device shaped like an anchor that could be towed on the end of a long wire. By steaming across the stern of a trawler, a gunboat could hook onto a trawler’s warps and sever them.

This was extremely dangerous for the trawler crews, and very expensive for the vessel owners in loss of time and gear. Despite protection by Royal Navy frigates, many UK vessels suffered the loss of a full set of gear.

The constant harassment by Icelandic gunboats led to a number of trawler skippers taking retaliatory action.

The aftermath

In May 1973, British Navy frigates were deployed to escort UK trawlers fishing at Iceland – but after a series of talks within NATO, they were recalled on 3 October. An agreement was signed on 8 November, 1973 limiting British fishing activities to certain areas inside the Icelandic 50-mile limit, and capping the UK annual catch there at 130,000t.

In 1975, Iceland further extended its fishery limits, this time to 200 nautical miles, triggering the third Cod War. This concluded with an agreement in June 1976 that reduced the UK’s annual catch within the Icelandic 200-mile limit to 30,000t.

For the ports of Fleetwood, Hull and Grimsby, whose fleets predominantly targeted distant-water fisheries, this was a disaster. Thousands of people employed in the fishing industry, both in the catching and processing sectors, lost their livelihoods, and hundreds of ships were sold or scrapped. Many experienced fishermen, especially older men, were forced out of the industry altogether.