The tenth article in the series by Hull skipper William Oliver, first published in 1953/54. Photographs courtesy of Alec Gill

Two months before our problems with poor-quality coal in 1926, I had been speaking to Mr McCann – the boss of trawler firms Pickering and Haldane and Yorkshire Steam Trawling Company – outside the office, and admiring a ship named Foamflower H 313.

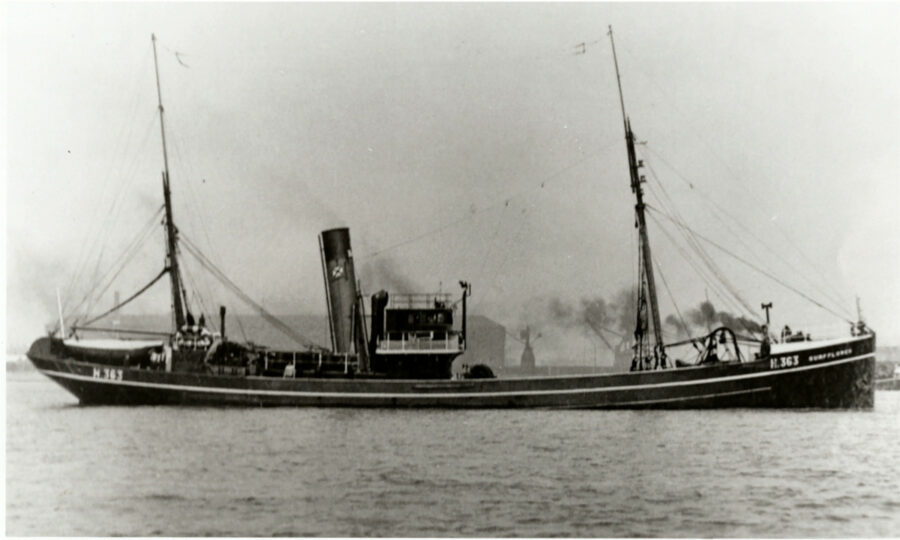

Surf Flower, pictured in the river Humber, was one of two new trawlers that Yorkshire Steam Fishing Co built around 1928 – the other was Sprayflower.

Some of the crew of Surf Flower.

Waveflower, built in 1929 at Cochrane & Cooper’s yard at Selby, pictured in the river Humber.

Skipper Oliver’s eldest brother, George Oliver, was washed overboard and lost when he was mate of the Hull trawler Jade (pictured here), in September 1928.

Waveflower’s success encouraged her owners to build Lord Brentford and Crestflower, pictured here alongside each other in Queen’s Dock in Hull, which was filled in during the 1930s.

Steam trawlers in Hull’s St Andrew’s Fish Dock in the 1930s.

Cochrane’s yard at Selby built many trawlers for the Hull and Grimsby fleets over the years.

Before the VD gear was introduced, the trawl was attached directly to the trawl doors, with no cables or sweeps being used.

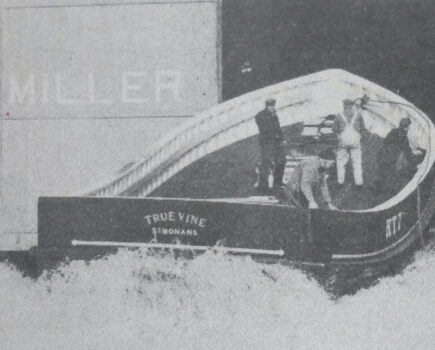

Stowing the fish on shelves instead of in bulk prevented crushing and was increasing at this time.

She was a new vessel built by Cook, Welton & Gemmell and was lying in the dock close by the P&H offices. She had been built for a certain firm, but it was understood that there was some difficulty about completion of payment for her. Mr McCann asked me what I thought of her, and I replied that I liked the look of her very much, and thought she was for sale. I also said that if the price was right, someone would get a very nice ship.

It turned out, in fact, that during my last trip to sea in October 1926, Mr McCann had bought her, and this was the ship I was to take. I was delighted about it, as she seemed to me an ideal steam trawler, and she afterwards proved to be so.

The next morning, I received a phone call from the office to the effect that Mr McCann would like to see me as soon as I could conveniently get down. On arrival, he informed me that as a result of serious consideration overnight, he had decided to reform the Yorkshire Steam Fishing Co with the Foamflower and that, if I wished, I would be allowed to become a shareholder in the new company. I was not to decide in a hurry, but to consider it carefully and give my decision on my return from my first voyage. I replied at once that it did not need a trip’s consideration, and the answer was a grateful ‘yes’.

So 20 years after being first engaged by Mr McCann as a skipper, I became a shareholder in his company. We made £1,996 the first trip and everything looked grand, but after two more moderate trips, I fell ill. Following an attack of influenza, pneumonia developed, and I had to have three trips ashore, my mate, G Booth, taking the ship as skipper. For the whole of February 1927 I was practically delirious and, although I returned to sea at the end of April, I have never been properly well since.

We continued to do fairly well, one particularly good trip next year being from Faxa Bay, making £1,870 for 16 days. It was whilst I was at home after this trip that I received news that my eldest brother, George Oliver, who was mate of the trawler Jade, had been washed overboard and lost his life, leaving a widow and eight children. This was in September 1928.

The Yorkshire Steam Fishing Co had built another two new trawlers, these being Surf Flower H 363 (skipper F Norton) and Sprayflower H 437 (skipper C Petersen – ‘Big Chris’). All these ships were doing very well, and the Yorkshire Co was prospering.

It was about this time that vessels started to go to Bear Island for fish. Trawlers had been there before; whether they had not been in the right place or whether they had gone in the off season, I cannot say, but they had been unsuccessful. Now, in 1928, they began to bring big catches of cod and codlings, with a fair proportion of haddocks, from Bear Island. By this time also, the filleting of fish at Billingsgate had started, and the Bear Island fish met with a ready sale. For myself, I preferred to remain at Iceland, and in the winter of 1928-9 had my best year ever.

Early in 1929, Mr McCann informed me that he was building a new ship for the Yorkshire Co. She was to be 150ft long, with the same beam and horsepower as Foamflower. In other words, another Foamflower with 5ft added to each end. This, he calculated, would make for increased speed. I was to take her, and my wife was granted the privilege of launching her. I felt greatly honoured. On 25 May, 1929, my wife launched the new steam trawler from Cochrane & Cooper’s yard at Selby and named her Waveflower H 58. On 12 June, I landed my last voyage in Foamflower – we were from the White Sea and made £1,250 for 22 days. On 26 July, we ran the trial trip of Waveflower. Everything was very satisfactory. She attained a speed of 11 knots, the fastest I had ever travelled in a steam trawler.

Waveflower proved to be a very successful vessel in every way. She had very good accommodation, and was light on consumption of coal, very speedy when necessary, and extremely handy to operate. We did very well in her, making very good payable trips right through the year. This encouraged Mr McCann to order several more ships of the same type. One was the Crestflower for the Yorkshire Co, another the Lord Brentford for Pickering & Haldane.

The class of fish now being landed from Bear Island was very good, and offered serious competition to the Iceland variety. All new ships being built for Hull were becoming larger and had a greater carrying capacity with each issue, and it became obvious that the catching power would very soon outstrip the merchants’ capacity to absorb and distribute the fish.

‘French gear’ revolutionises trawling

An important development around this time was the introduction of the Vigneron-Dahl (VD) or ‘French’ gear that the French fishing industry had begun using.

It was introduced in Hull in 1928 and was a highly efficient gear that revolutionised fishing.

Formerly, the trawl was shackled on directly to the otter boards, and the trawl and doors lowered away preparatory to shooting. With the French gear, the trawl was shackled onto a kind of spreader termed a Dan Leno. This spreader was, in turn, connected to the otter door by cables, or sweeps or bridles as they were known in other ports. The cables were of varying lengths according to the nature of the ground, rough or smooth. The ideal lengths were found by experience to be 50 fathoms in smooth ground and 20 fathoms in rough.

The sweep of the otter doors covered a wide area, and the bight of the cables scraped on the bottom of the sea, digging out the flatfish. The headline of the trawl was now interspersed with metal floats, thus increasing the height of the mouth of the trawl. A vastly increased catching power was thus created, which would in time gradually denude all the well-known grounds of fish.

Great difficulty was experienced at first in preventing chafe of the lower wings of the trawl, and invariably in rough or hard ground, the lower parts of the trawl were torn away on every haul, owing to the cables biting the ground. With characteristic patience, however, the fishermen gradually overcame this difficulty by adopting certain changes, with the result that today it is no more of a problem to operate French gear than the previous types. Nevertheless, it was the cause of many anxious trips for the pioneers before it became successful, and the younger generation certainly owes a debt of gratitude to the older fishermen for overcoming the difficulties.

Trawlers shelve more fish

Another change that was growing in importance at about this time was a difference in the method of icing fish. I refer to the shelving of cod, sprags and haddocks. Although shelving had been adopted years before I went to sea, it was only done on the last haul or two in the near waters, and about 24 hours before landing. Then it gradually spread to Faroe ships and proved very successful. In time it came to be adopted by the Iceland ships. First, only the last few hauls were shelved; then, as fish gradually became scarcer, the time was extended.

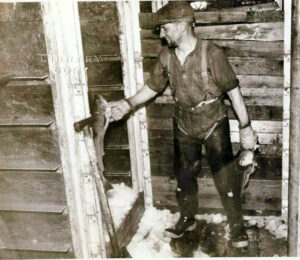

Ordinarily, of course, when fish is stored in the fishroom, a certain quantity is thrown or laid in the pounds and then covered with ice, then another quantity and another covering of ice, and so on until the fish reaches a certain height. Then, to prevent undue crushing, boards are placed on battens which are covered with ice, and the operation continues. These shelf boards take the weight of each succeeding quantity of fish from those underneath, so, as will readily be understood, the more shelves there are in a fish pound, the better the condition of the fish is likely to be.

The operation of shelving was on the same principle, except that every layer of fish was self-contained. Every board in the pound has a batten, and on those battens boards were placed, covered with ice and fish laid upon them, but no ice on the fish on top. This enabled the fish to be landed without any signs of crushing and unmarked by ice. It meant, of course, that there was much waste space in the fish pound, but as the larger type of trawler was very rarely filled, that did not really matter.

Occasionally, owing to the better appearance and quality of the shelved fish, it made much better prices than the bulked fish, but in time, shelving nearly defeated its own object. Before the last war, the larger types of trawler could spare a large amount of space for shelving and, owing to the quota on catches which was imposed about 1936-7, never filled up. The merchants could sometimes satisfy all their needs with shelved fish, the bulked fish remaining unsold.