The 11th article in the series by Hull skipper William Oliver, first published in 1953/54. Photographs courtesy of Alec Gill

As well as new ships becoming larger and having a greater carrying capacity, a still newer departure was made in the construction of Hull trawlers with the launching in 1931 of the first cruiser-stern trawler, the Beachflower H 349, for the Yorkshire Steam Fishing Co.

Waveflower, Skipper Oliver’s last ship with the Yorkshire Steam Fishing Co, leaves Hull’s St Andrew’s fish dock on another trip.

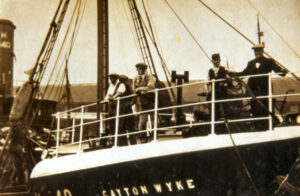

Cayton Wyke was one of the first cruiser-sterned trawlers in Hull, built in 1932 for the West Dock Steam Fishing Co.

The crew of the Cayton Wyke on the whaleback as the trawler leaves St Andrew’s dock.

The crew of the Crestflower, a Yorkshire Steam Fishing Co vessel, prepare for another trip as the vessel heads into the river Humber from Hull’s fish dock.

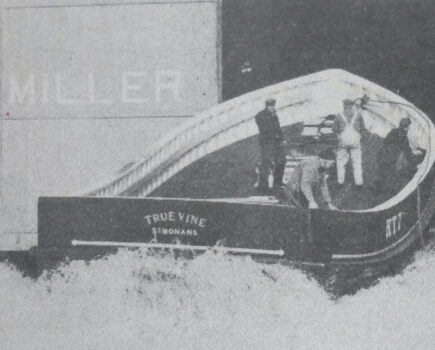

Bayflower, seen on trials in the Humber…

… and Rockflower were part of the fleet of successful cruiser-sterned trawlers operated by the Yorkshire Steam Fishing Co in the early 1930s.

William Oliver skippered the Kopanes, pictured on the slip in Hull, or two trips in September and October 1933.

Trawlers tied up in Hull’s fish dock during a deckhands’ strike in 1935 over a cut in their earnings from liver oil money.

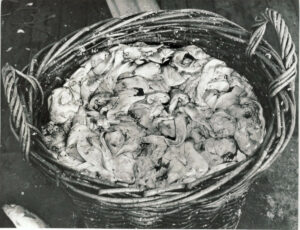

Livers were saved into baskets and boiled to make codliver oil.

She was followed very quickly, early in 1932, by the Cayton Wyke H 440, another cruiser-stern vessel belonging to the West Dock Steam Fishing Co. These cruiser-stern ships represented a distinct improvement in construction, as they were faster, subject to less vibration, and did not drag in the water, causing what I call a ‘quarter wave’ when running before a heavy swell. Other firms quickly followed suit, and I do not think there are today half a dozen ships in Hull without the cruiser stern.

We had two very successful years in the Waveflower and then, for some reason I do not quite understand, our earnings started to fall considerably. Rightly or wrongly, I put it down to the following reason.

Mr McCann, the boss of Yorkshire Steam Fishing Co, had always been of the opinion that a good deal of coal was being consumed in his vessels unnecessarily, and always tried to instill into the minds of his skippers never to operate at higher revolutions than necessary for efficiency. I have to admit that I agreed with him, and so I never gave orders for Waveflower to be driven unless it was to catch a market. Most trawlers by this time were being driven hard towards the fishing grounds and home the same way, but I carried on economically both ways.

I had also tested Waveflower at various towing speeds from the time she was new, and had fixed on 78rpm as being the ideal. The fishing grounds, however, were getting barer, and many trawlers were now towing at 84 to 86rpm. I had tried this higher figure once or twice but, whatever the reason may have been, the result was not very satisfactory. So I continued at 78, but there was no doubt that I was not catching the fish that my colleagues were taking, and they were getting in more fishing time owing to their faster passages. Although, therefore, we were the lowest in consumption of coal in the whole fleet, we were also nearly the lowest in landings.

One of my previous mates, Norman Goff, was now skipper for the Yorkshire Co in Crestflower H 239, and my son Lawrence was in another Yorkshire vessel, Sprayflower H 437. There had been several new additions to the Yorkshire fleet: Rockflower H 511 and Bayflower H 487 were fine cruiser-stern ships, and the Yorkshire Co was doing very well, with the one exception of Waveflower. This began to get on my nerves and I started to imagine all sorts of complaints and grievances. My health was also causing me some concern, as I had a good deal of bronchial trouble – a legacy of my pneumonia in 1927.

A career mistake

In 1933, I decided I would leave Waveflower and sever my connection with the Yorkshire Steam Fishing Co. So, in August of that year, after landing a disappointing trip, I left a letter to be posted to Mr McCann after I had sailed, in which I expressed my desire to resign, and also offered the shareholders my holding in the firm. It now seems to me that I must have been demented to do such a thing, but I was so dissatisfied by my earnings at the time that it seemed the only thing to do. On my return from Iceland in September 1933, I ended my connections with the old firm and with Mr McCann, and it is fair, I think, to say that I took very little interest after that in fishing as a skipper.

Having settled up with the Yorkshire Co, my wife and I went to London for a week to see one of our sons who was in Manor House Hospital undergoing treatment for an injury caused at sea, and for which he had had several operations.

On my return to Hull, I had an interview with Mr W Willey, to whom I had previously intimated my intentions. He made an offer to buy a suitable ship if I would sail in her as skipper. The ship selected was the Kopanes H 502 belonging to J Oddsson; she was a fine type of trawler. Negotiations were completed, and I sailed as skipper of Kopanes in the last day or two of September 1933.

We made two ordinary trips, and then Mr Willey asked me if I would transfer to Pennine H 268, as J Dahlgrean, her skipper, who had been with the Willey Company some three years, considered that he had a right to the better ship. Mr Willey assured me that if I would agree, he would order a new ship which would be for me. On those conditions I agreed, and changed to Pennine in early November. She was a much smaller type of ship and I didn’t like her a bit, but we did very well in her and I was more or less content.

When the new ship, the Mendip H 114, was ready, I did not get her. Skipper Dahlgrean got her and I transferred back to Kopanes, by then renamed Grampian H 502. This was in October 1934. I remained in Grampian, and another ship was ordered which was supposed to be for me. We did fairly well, although I had two trips ashore in December and January. On one of those trips, R Millener took her away and made £2,000 from Bear Island.

In March 1935 came a deckhand strike, as a protest against a reduction in the price of liver oil money. Oil money was derived from the oil made from the fishes’ livers, which were saved in baskets when the fish were gutted, and boiled onboard. Oil money made up a significant proportion of deckhands’ earnings.

We had landed just before Good Friday and made £1,448. The strike went on for about five weeks and resulted in the men going back with half the reduction reinstated. I remained in dock for three weeks, and sailed in Grampian again at the end of April.

25 years as a skipper

In May 1935, I received two wires, one from my wife and one from my owners, congratulating me upon being awarded the King’s Personal Souvenir Jubilee Medal for services in the fishing industry as a skipper for 25 years. Three Hull skippers were granted this honour – skippers Glanville, A Albrow and myself. The presentation was made at the Trawler Owners’ Association offices on my return from sea.

We carried on in Grampian, doing fairly well, until one trip in October 1935. We were at the White Sea off the north coast of Norway when I learned that I was not to take the company’s new ship after all, and that J Dahlgrean had been promised her. Mr Willey, I regret to say, did not appear to keep his word to me, so on my return to port I left the company.

I now decided that I had had enough of the sea, and entered into negotiations with the Hull Brewery Co, with a view to taking the tenancy of a country public house where I hoped to finish my days. When we presented ourselves for an interview with the manager of the company, however, my wife dropped a bombshell by disclosing that she was not in favour of life spent in a pub, so the whole thing was called off and I decided that I would in due course return to sea.

In December, I received an invitation from Mr J Oddsson to go as skipper in his vessel Brimness H 588 sometime in January, subject to certain bonus conditions. These were agreed, but I made the stipulation that in consideration of foregoing a summer holiday, I would be allowed two trips ashore in December and January. This was also agreed to, and on 26 January, 1936, I sailed in Brimness to Iceland.

We had varying luck in Brimness, but on the whole we did fairly well. At any rate, Mr Oddsson was satisfied, and he informed me he never had a ship run with so little expense as we had had. I landed in December and received a fairly comfortable sum in bonus, and then stayed ashore for the agreed two trips.

Most of the time that I was ashore during that winter I was suffering from bronchitis, and started to lose weight very considerably. The Brimness had gone to the White Sea and was away for over a month. On her return she made a poor trip, and Mr Oddsson said he intended to keep her in dock for a few days and put her on slip. Would I take her when she was ready, as I should have been ashore five weeks by then? He did not absolutely insist, but considered it would be much better than putting another temporary skipper in her for a trip. I did not care for the idea as I was anything but well, but did not care to refuse. I made a very big mistake.

We sailed on 21 January, 1937, and went out of the river into a heavy SE gale. We had to pull to head to wind and, after 36 hours’ dodging, the chief engineer reported that both his firemen were down with flu. We could not get into Aberdeen as the port was closed owing to the gale. After some time, I got up to the Moray Firth and obtained medical assistance at Fraserburgh. Our two firemen were landed and put into hospital, and replacements were signed on. It was still blowing a gale and impossible to run for the Pentland Firth.

That day, signals of distress were sent out by Amethyst H 455, one of the Kingston Co vessels on homeward passage. Nothing more was heard of her, and she was lost with all hands.

My chief and second engineers now had flu, and the next morning I had it myself. So I decided to return to Hull, feeling that it was impossible to continue the trip. So just over a week from sailing, we dropped anchor off the Victoria Pier, a relief skipper came onboard, and I went home and was immediately put to bed, where I remained for three weeks. This, then, I thought, finishes me as a skipper: I imagined that my services would no longer be required after that.