The ninth article in the series by Hull skipper William Oliver, first published in 1953/54. All photographs courtesy of Alec Gill

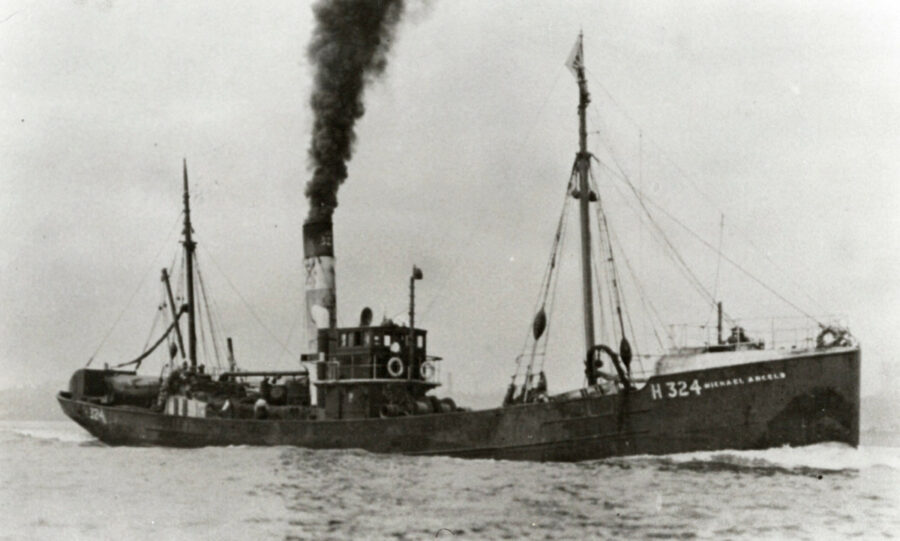

After returning to civilian life after the war, I left St Andrew’s Dock as a skipper once again on 21 February, 1919. I was in the Michael Angelo H 324, belonging to Pickering & Haldane’s Co (P&H) and bound for Iceland. I had been away from fishing for four and a half years, but the first day I started again, it was as though I had never left it.

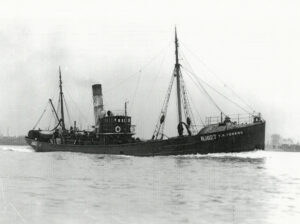

William Oliver made his first trip after the end of the First World War as skipper of the Michael Angelo, fishing at Iceland, staying in her for five trips.

Great changes had been made in the industry by this time. Three box fleets had ceased to operate in 1919. The Great Northern and Hellyer’s box fleets had been disbanded, and the Red Cross fleet had been sold and merged with Beechings into the Gamecock fleet.

Several big firms had gone out of existence, and trawlers were realising fantastic prices. Vessels which had cost £8,000 new to put to sea were now realising as much as £24,000. Several new firms had sprung up, notably Hudsons & Storrs.

To replace losses of trawlers during hostilities, the government had embarked on a large building programme of new vessels in three classes – the Mersey class, so-called after the Lord Mersey, a new vessel belonging to P&H; the Strath class, an Aberdeen type; and the Castle class, a West Country type.

The Mersey type of vessel was particularly suitable for Icelandic fishing, being 138ft long and 23ft 6in beam, and carrying 240t of coal. Many of these vessels were not now required by the Admiralty and were placed at the disposal of the owners for use in the industry. A great number of them were acquired by Hull owners, and it was not long before Hull’s pre-war strength of trawlers was attained.

Lord Talbot was one the new Admiralty Mersey class of trawler, which were arriving in Hull from 1920 onwards. Skipper Oliver took command of Lord Talbot in October 1921, and skippered her for two and a half years.

Controls had been imposed on the sale of fish during the later years of the war – plaice at £7 10s per kit (10st) and cod and haddocks at £4 10s per kit. These prices still prevailed for a few months after the Armistice, when trawlers still sailed in convoys, but both controlled prices and convoying were discontinued by June 1919, when free markets applied again.

I had been skipper of Michael Angelo for five trips to Iceland, when all fishing in Hull stopped for a time because of a trawler engineers’ strike. They wanted a rise in pay besides another trimmer below in distant-water vessels. Trawlers were continually being bought and sold, Michael Angelo figuring in one such transaction.

I was transferred to Peary H 1016 (P&H), but before she sailed she also was sold to Cargills (afterwards Jutland Amalgamated Trawlers), but it was a condition of sale that I should command her until P&H had another ship for me. I sailed in Peary (afterwards renamed Scapa Flow) for two trips, making £2,600 each trip, after the engineers’ strike had finished.

I then took command of TR Ferens H 1027 (P&H) for four trips, when she in turn was sold to Icelandic owners. Then I took Lord Minto H 105 in February 1920, and sailed regularly in her.

William Oliver became skipper of the Peary for two trips after leaving Michael Angelo, which her owners sold. Peary was later renamed Scapa Flow.

Vessels were being put into increasing circulation with every passing month, as fast as they could be reconditioned, and by 1921, there was a plentiful supply of fish coming in from the grounds. Prices were fluctuating, but on the whole they remained fairly good, and I would say that the industry at this time was in a very prosperous condition. At any rate, I was getting a fair average living out of it.

Then, in May 1921, came a coal miners’ strike, and the industry again became very disorganised. The price of bunkers in Hull was then about £1 per ton, and it became possible to go to the Continent and obtain coal at about £3 per ton. Many vessels were laid up, but some went abroad for coal.

I went to Antwerp, where we bunkered with a fairly workable class of coal. We made £2,850 from Iceland, and then went to Ostend for a further supply. We made our next trip off the west coast of Scotland, and realised £1,100 for a 10-day trip. After these trips, I was obliged to lay my ship up to give some of the others a chance, but I was very well satisfied. The coal strike ended in early July, but we remained in dock, undergoing refit until 30 July, when we sailed again.

By 1921, the Admiralty Mersey class of trawler was arriving in increasing numbers at Hull, reconditioned for fishing, and P&H had obtained 12 of these. I remained in Lord Minto until October 1921, when I was given command of Lord Talbot, one of the new Mersey class.

TR Ferens was sold to Icelandic owners after Skipper Oliver had commanded her for four trips in 1919.

We left the Humber in a heavy northerly gale, and by the time we had arrived off Whitby, owing to a defect in the bunker lids, we were full of water in the bunkers. It was a very sticky and uncomfortable position, with a heavy gale blowing from NNE. The pumps became choked with coal dust, which had found its way into the bilges with the water.

However, we managed to keep afloat, and at daylight we managed to get a lee from the Farne Islands, and have a look round. We got the bilges and pumps cleared, and after packing the bunker lids round with rope yarns and grease, got all the water out of her and went on our way – but it was nasty while it lasted.

I did very well in the Lord Talbot, being at that time one of the top men in Pickering & Haldane’s. The bonus system had been restarted after the war, the initial figure now being £15,000 instead of the £6,000 when it was originated. Then, in 1922, P&H started a system of prize money to encourage the skippers to further effort. The first prize was £500, the second £200 and the third £100. These sums were in addition to the ordinary bonuses.

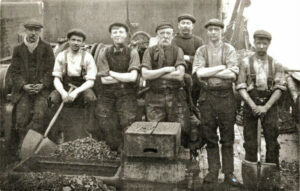

A gang of coal trimmers pictured on Hull’s St Andrew’s fish dock before the First World War.

The prize system was that the skipper who had the largest gross earnings got the first, and so on, each operative from a given date for a completed year. This system was discontinued after two years, but for the two years it was in operation, I was lucky enough to get the second prize each year.

I remained in Lord Talbot for two and a half years, and was then transferred to Lord Gainford, another new vessel of the Admiralty Mersey class 1924. I was maintaining my position as one of the top men for earnings in P&H, and all the inconveniences of the war were long since forgotten. I had a family of 10 – five sons and five daughters – and by this time three of my sons had started to go to sea as fishermen.

Then, in April 1926, came the next miners’ strike, followed in a short time by the general strike of all industrial workers – except fishermen. The industry once again became disorganised, and hundreds of vessels were laid up. We were one of the vessels selected to keep going, and we went to several places on the Continent for coal, including Rotterdam, Schiedam and Ostend.

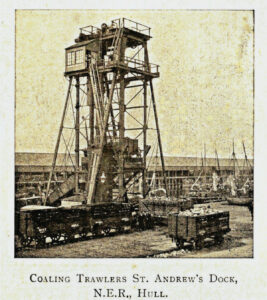

Trawlers being coaled at Hull’s fish dock in 1915. The last coal burner in the Hull fleet, Othello, was scrapped in 1963, at the beginning of the Humber freezer trawler era.

The coal was of very poor quality and mostly underweight and expensive, but we managed to carry on making trips. Then for one trip we went to Hamburg for our coal. We obtained 200t at £2 15s per ton, but as soon as we left port, it was apparent that we should have difficulty in burning it. We steamed northwards, but by the time we arrived off Buchan Ness, it became very doubtful whether we should be able to maintain a sufficient head of steam to carry on fishing operations. So we decided to shoot the gear and give it a trial before proceeding further.

We shot the gear in 38 fathoms of water, but after the trawl had been down an hour, it became impossible to tow, as the utmost revolutions we could manage was 60. There was no alternative then but to turn the ship round and return to Hull. I was very worried about it, but was considerably heartened when I learnt upon arrival that four other P&H vessels who had obtained coal at Hamburg were obliged to do the same.

We laid in dock a few days and had all this coal taken out, and I believe it was disposed of to the icehouses which, having forced draught, were able to use it. Then we went to Ostend again and got a fairly workable class of coal, and proceeded to Iceland.

We made a very nice payable voyage. After we had landed, I was told by Mr McCann that I was to stay ashore and take another new vessel. Many of the trawling companies had started building new ships by this time, the whole of the Admiralty ships having been absorbed into the industry.

Danish seining at Hull

A new departure in fishing from Hull made its appearance about this time – the Danish seine-netting. Several firms purchased small vessels to engage in this class of fishing, and P&H had 12 small vessels built for the purpose.

For a time, it seemed as if seine-netting would drive the trawlers out of business, but their range was extremely limited, and it was necessary to operate on smooth ground. I was asked by Mr McCann if I wished to take up this class of fishing, but I declined, as I preferred to pin my faith in trawling.

The seine-netters were taking their toll of the grounds in the North Sea, which rapidly became denuded of fish, and as the vessels were not suitable for a longer range, seine-netting gradually declined in Hull until, at the end of two years after its inception, it ceased.