The Lincolnshire town’s fortunes have gone up and down – like its fishing. John Worrall reports

The Lincolnshire port of Boston goes back a long way.

Boston first got rich in medieval times through the Hanseatic League, whose success was substantially based on its ships, specifically the cog – a replica of which visited Boston in 2004.

Sited on a river – most ancient ports were – it started modestly as a transshipping point for Lincoln, the city well inland up the river Witham, which had formed around a Roman fort on a ridge. By the 11th century, full of industrial and religious energy, and by then building a cathedral, Lincoln was sucking in imports, and the Witham was the main conduit.

But like all pre-drainage Fenland waterways, it was an indifferent navigation, shallow and shoal-ridden, taking flat barges but often nothing that drew much water. Back then, it issued into the Wash through several channels, the main outfall probably at Wainfleet, 10 or so miles north of the present-day river – although traders used any convenient creek, and likewise the fishing boats working the cockle and mussel beds of the Wash.

It was probably in the ninth century that some storm or inundation threw up the alluvial banks on which Boston was to properly develop, beside what became the only channel, and nearer to the sea than it is now, before reclamation and accretion pushed out the shoreline. Expanding North Sea trade in the 11th century consolidated the port.

Boston didn’t feature directly in Domesday of 1086, but the town would have been established by then, the name probably deriving from the fair that started on the feast of St Botolph, to whom the church was later dedicated. That huge edifice, a reflection of the town’s medieval wealth, was begun in 1309, although its tower, 272ft high and known as the ‘Stump’, wasn’t finished until the 16th century.

The Stump would become – and remains – a landmark for sailors in the Wash, but many still perished within sight of it, embayed by a northerly, with their only hope of avoiding a lee shore being to make it over barely charted shoals to one of the four river mouths. In 1692, a big northeaster wrecked 50 ships in the Wash and another 140 along the North Norfolk coast, most of them colliers hauling coal from the North East to London. A thousand lives were lost that night – though Wash fishermen would probably have seen the signs and got in before it arrived.

The town’s wealth really began to accumulate in the 13th century because of the Hanseatic League, the German trading cartel which, attracted substantially by English wool, lifted Boston’s trade to a different level. A key to Hanse success was its shipping, principally the cog, a new dimension in sail trader.

The cog – the replica is seen here at King’s Lynn, another Hanse port, on the same trip – was bigger and stronger than other ships of the time…

Though single-masted and square-sailed, cogs were much bigger and sturdier than most ships of the time, which were still mainly Viking-style derivatives, and though not much good to windward (neither were most others), they sailed short legs, mostly in sight of land and moving only when the wind was in a comfortable quarter. They would run southwest on the spring easterlies from their north German bases, down to the narrowing of the English Channel, trading as they went, and moving over to southern and eastern England with the summer breezes, returning home in late summer on the then usually reliable westerlies.

The first Hanse merchants arrived in Boston around 1230, and the town soon overtook Lincoln commercially through the growth and export of East Midlands wool, its transportation helped by the Foss Dyke, the Roman waterway that had been reopened in 1121 and ran west for 11 miles from Lincoln to Torksey on the river Trent. Boston became the principal wool port for the whole country, an average of 10,000 sacks per year – roughly a third of all English wool exports – going out to spinners and weavers in the Low Countries and elsewhere, while nearly two million litres of wine came in each year. In 1289, Boston paid more customs duty than any other English port, and in 1332, with 5,000 people, it was the fourth wealthiest provincial town.

But by then, its inland connections were beginning to fade. The Foss Dyke had silted again, and the shapes of politics and commerce were changing. The Hundred Years’ War, which began in 1341, crippled the wine trade, while domestic cloth-making in East Anglia and the Cotswolds absorbed wool production and vastly reduced wool exports. Famine and plague added to the decay, and Boston went into four centuries of decline, except that some of its fishermen were part of the medieval English fleet that spent summers working off Iceland – even if arriving back in the shoal-ridden Wash in the wrong conditions could be as tricky as anything they encountered in the North Atlantic.

… with plenty of deck and hold space…

The Hanse merchants finally decamped in the early 16th century, aggravation having added to decay, such as the incident in 1470, noted by the 16th-century English antiquary John Leland, in which ‘one Humphrey Littlebyri, merchant of Boston, did kill one of the Esterlinges. This caused the Esterlinges to quit Boston, and syns the town sore decayed.’ Well, it would, really.

The Reformation’s culling of the monasteries and guilds drained most of any remaining money out of the local trading equation, and the port in the 1570s was described as ‘destitute of ships and trade of shipping’. In 1584, nothing went out except 260 quarters of barley and wheat – though that was partly down to the fact that the river itself had silted and ships of any size struggled to get in or out. That was why the Pilgrim Fathers, making their first attempt to leave England in 1607, did so from well below Boston, where there was just about enough water.

Those cod smacks, nevertheless, were still working their way in and out for the Iceland trips – though by then they were having trouble with Dunkirkers, the privateers working out of the Low Countries for the Spanish crown, who captured any shipping they could. Cockles and mussels on the Wash sands were an easier – if not necessarily so remunerative – option.

But then, in the 1760s, another commercial upturn came, following the drainage of the vast Holland Fen to the west of the town. This converted summer grazing into arable land, and brought an agricultural revolution, the produce of which needed to be shipped to the large centres of population. Boston port got the business, and some of the profits were spent on river improvements, including the building of the Grand Sluice, completed in 1766, to hold back the tides and increase scour with releases of freshwater.

… and advanced technology…

It wasn’t a perfect solution, and the river still had its difficulties, which meant that trading ships generally remained small, averaging 52t in the 1790s and 45t in the 1840s – although those averages did include smacks, and bigger ships could be edged up on the right tide. When the firm of Abraham Sheath & Sons of Boston went bankrupt in 1814, its fleet included one brigantine of 300t and six more averaging 115t. Things were going reasonably well for the port, and by then fishing boats were staying local.

Further momentum came in the early 19th century with the growth of coastal traffic for the Napoleonic War effort. By 1812, with more fenland reclaimed, one-third of the oats reaching London went through Boston, and by 1828, at least 55 ships were working that route, with knock-on business for ancillary port trades: sail-cloth, canvas, sacking, and iron and brass foundries. By 1848, Boston was again the largest and richest town in Lincolnshire.

Except that 1848 was the year the railway arrived, and with exquisitely bad timing, it was followed by a hard winter which froze the river, so that the only produce to leave went by rail. The new technology retained the action, and port prosperity evaporated again.

In reaction, Boston Corporation decided to fix the river once and for all, and in 1884, the stretch below the town, then known as the Haven, was shortened by over a mile to five miles, with the lower reach hooking northeast into the Wash to take and release tides efficiently. At the same time, the Grand Sluice was widened and deepened to further reduce silting and, crucially, the corporation built a dock on the edge of the town. Suddenly, ships of 2,000t could get up on spring tides and not dry out. By 1896, cargoes handled had increased eightfold.

… including, instead of a steering oar, the newfangled centre-mounted rudder, which was a bit of a handful and needed to be lashed in position.

And suddenly, fishing – at that point still in the smack era – could start to think big – or bigger. Already with a steady supply of cheap labour from orphanages, reformatories and workhouses, whose lads were tied into penurious seven-year apprenticeships – the Merchant Shipping Act 1880 was supposed to stop that, but there were ways round it – Boston’s fishing embraced steam technology with alacrity, and looked again beyond the Wash.

The first step was the formation of the Boston Deep Sea Fishing & Ice Co at a meeting at Boston Guildhall on 7 August, 1885. The company was backed by several investors, and it appointed Alfred Wheatley Ansell as its first MD. He immediately, and somewhat dubiously, managed to sell seven smacks to the company for £9,000, although on condition he took 100 fully paid shares at £10 each – which may or may not have amounted to convincing window-dressing.

Two new steam trawlers were then ordered from Earles of Hull. These launched in November 1885 – though they stretched finances so much that the company had to borrow £8,000 from the main shareholder, and most of the boats were only insured for two-thirds of cost.

At that stage, the new dock didn’t have many fish-handling facilities, and the new boats were initially based at Hull. But a 200ft fish quay was built, and in April 1886, four vessels – Witham, Holland, Kesteven and Lindsey – steamed up the Haven, and not before time, because fish merchants were complaining about erratic supply. Straightaway, the company ordered two more trawlers, from W Holmes of Hull.

The strength was in the timbers…

There was the odd administrative problem. Ansell was dismissed for allegedly receiving commission from Earles on the first two trawlers, and over the condition of the smacks he’d sold to the company – though he sued for wrongful dismissal and won. And there was a report in April 1887 that trawlers were trading fish at sea for gin and whisky, which they smuggled in. But then, if you had pressed your crew into penurious apprenticeships, it might perhaps have assuaged your conscience to have spread a little joy. Or perhaps not.

By May 1888, the company had 10 steam trawlers, and eight of the old sailing smacks – including the seven bought from Ansell for £9,000 three years previously, which were offloaded at the end of that summer for £1,275 in total. Ansell wasn’t re-employed.

In 1889, another six trawlers were ordered – two apiece from Earles, Finch & Co of Chepstow and Rennoldson’s of North Shields – and in 1897, the company amalgamated with the Steam Trawling Co, increasing its fleet to 24. Two more trawlers were added in 1898.

The trouble was that fish prices had always been lower than at Grimsby. By the start of the First World War, the company was struggling, and then the war itself brought huge disruption.

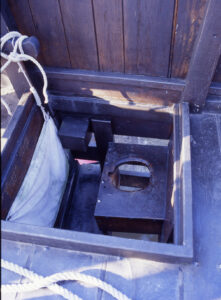

… and social refinement in the outside toilet – though beware a following sea.

When Britain joined the war on 4 August, 1914, fishing stopped completely at first because the sea was suddenly full of mines. Ports became filled with boats, and allied trades’ order books emptied. Some younger crew enlisted in the forces, thinking that land fighting would carry less risk than the chances of being blown up at sea. Little did they know.

By late August, however, fishing boats were edging back to sea, and then the price of fish was put into a different perspective, because several were lost in quick succession.

On 22 August, seven fishing boats from Boston, including six belonging to the company and another, Capricornus GY 750, owned by the Grimsby & North Sea Trawling Co Ltd, were stopped by submarines, their crews taken prisoner and the boats sunk by gunfire. Then, from 24 to 26 August, three more from Boston and a dozen from Grimsby got the same treatment.

Fishing effort remained limited because by then, many trawlers were being commandeered for Admiralty service, specifically for minesweeping, to which their power and endurance were suited, even if their greater draught than that of drifters made them more susceptible to mines.

Submarines were the other main danger – more so than German surface warships, the latter having been mostly withdrawn to port after the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28 August, when losses put the wind up the Kaiser so much that he decreed that the fleet should ‘hold itself back and avoid actions which can lead to greater losses’, much to the outrage of his commanders.

(During that battle, the cook on the brand new light cruiser HMS Arethusa was preparing breakfast when a shell came through the galley and took his arm off, and he would have bled to death, had he not found an empty cigarette tin and clapped it on the stump – a rare example of smoking saving a life.)

After the war, Boston’s fishing had a further – albeit very brief – surge.

A Dutch replica visited in 2015, seen here on 10 May that year, working along the Norfolk coast on a spring easterly.

In May 1919, local poor boy made good Fred Parkes joined the board of Boston Deep Sea, and during the early 1920s, he gained control of the company. Already in fish merchanting, he had bought several Admiralty trawlers still under construction, and had even been poaching the company’s crews.

Boston Deep Sea was still the biggest employer in the town, even though its fleet after wartime losses and secondments was down to six. A flurry of activity in 1919 saw 11 more government trawlers acquired.

Things were going swimmingly until 28 February, 1922, when a collier, the SS Lockwood, grounded in the Haven, and the harbour master asked the company to send a trawler to assist. The William Browns did so and got the Lockwood off, only for her to ground again on the ebb near the river mouth. And then, on the flood, she was pushed across the river and capsized, largely blocking the channel and leaving only enough room for small ships to squeeze past at high water.

The banks on either side then began to erode, and when salvage companies were told that if the banks breached, they would be liable, none would touch the job.

The Pilgrim Fathers tried to flee the country from Fishtoft below Boston, where there was enough water for their ship – but they were caught and prevented on that attempt.

So Parkes did it, on condition that the council met expenses – but when he presented his bill for £12,000, the commissioners, on behalf of the corporation, refused to pay, saying that it was Parkes’ company that stood to gain most from the reopening of the Haven. With the ship’s owners also not coughing up, litigation ensued, and although it was settled out of court for £10,000, Fred was so annoyed that he decided to move to Fleetwood. By June 1923, much of his fleet had gone.

The final blow to Boston’s standing as a trawler port came in 1924 when Stringer, the other remaining Boston-based company, left – although its fleet was anyway down to three trawlers by then.

These days, Boston’s fishing is back to being local again, with 26 boats working the Wash, tying up on the river and going out, along with those from King’s Lynn, across the Wash, for cockles, shrimps, whelks and – when there are any – mussels. Cockles are the biggest number, that hand-worked fishery starting in mid-summer and lasting until late in the year on an average TAC.

And commercial trade continues, the port run by the Victoria Group, trading with continental Europe and Scandinavia. Sail stayed quite late, the last sail trader to leave being the schooner Frida on 18 December, 1932.

A few years back, there was a cog in Boston port once again, a replica of one found in the river mud near Bremen and authentic in every observable detail – including the huge oak timbers and outside toilet.

But there was of course a chunky diesel below, which made lee shores less of an issue.

Further reading: Boston Deep Sea Fisheries, by Mark Stopper and Ray Maltby