She lies in isolated decline in South Georgia – but there are multi-million-pound plans to bring Viola, the world’s oldest viable steam trawler, home. Brian W Lavery reports

Viola lies rusting, her mighty heart stilled, 8,000 miles from home in the sub-Antarctic island of South Georgia, a place for which the word ‘remote’ barely suffices.

01. The Viola in her current resting place in South Georgia.

02. Despite half a century of neglect, the Viola is in great shape for her age.

03. The steam trawler Viola, pictured in around 1907.

04. The crew of a boxing trawler, photographed in summer 1910.

05. The boxing trawler crew at work.

06. Transferring boxes from a trawler to a steam cutter in the open sea.

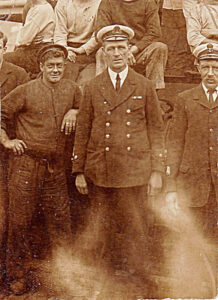

07. Viola skipper George William Tharratt.

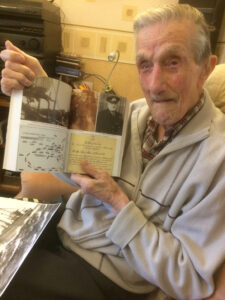

08. 103-year-old Eric Tharratt looks at his father’s photo in the book about his former command.

09. Naval architect Rosalind Blazejcyk and salvage expert John Simpson, from Solis Marine of Hull, survey Viola to assess the feasibility of bringing her home.

10. Viola lies next to the rusting hulks of Albatros and, further away, Petrel.

The explorer Ernest Shackleton lies buried a stone’s throw from her final berth on Cumberland Bay, where also lie the decaying hulls of two whalers. Here, the albatrosses and petrels outnumber humanity by thousands to one.

This place came to the notice of the wider world only three times in a century. In 1916, Shackleton sailed in a small open boat with a tiny crew from Elephant Island across atrocious seas. His party fell upon King Haakon Bay, and Shackleton and two others then crossed glaciers and mountains to a whaling station, from where they returned to rescue their marooned men. This real-life Boys’ Own adventure made worldwide headlines.

In 1922, Shackleton died there of a heart attack on his ship Quest, having been due to return to the Antarctic. Sixty years later, Argentine scrap dealers landed nearby and sparked another worldwide story – the Falklands War.

Viola’s history reads like the stories of Herman Melville or Jack London – from trawling to minesweeping to submarine hunting, then whaling and taking seals, and latterly hosting expeditions in the South Atlantic. The first was the Kohl-Larsen Expedition of 1928-29, which took the first cine film on South Georgia. Others included the British South Georgia Expedition and those for biological work carried out by the Falklands government.

Viola’s story began in 1906. The steamship was built in Beverley, East Yorkshire, as part of a boxing fleet operated by the Hellyer Steam Fishing Company of Hull. Boxing fleets were an early form of industrial fishing, named after the boxes in which fish were packed. These were transferred at sea in open rowing boats to fast steam cutters bound for London to feed the insatiable monster of Billingsgate’s fishmarket. The railway boom boosted reach – and trawlermen and cutter crews continued to risk their lives so the Lancashire mill girl or the Yorkshire coalminer could have their fish and chips.

Hellyer’s Hull boxing fleet joined three others – the Great Northern, the Red Cross and the Gamecock. The latter was famously fired upon in 1904 when the Russian navy mistook the vessels for Japanese warships. This almost sparked a European war long before 1914. Charles Hellyer’s fleet launched in 1906, and he named most vessels after Shakespearean characters. Like her Twelfth Night namesake, Viola landed on a foreign isle – but with a less happy ending.

Viola left the Humber in 1914 when she was requisitioned by the Admiralty as a minesweeper. She and her crew sailed to war under the command of skipper Charles Allum, a London waiter’s son who had come north seeking adventure. He was not disappointed. Viola was on the maritime front line for four years. She steamed thousands of miles across U-boat and mine-infested seas, more than any dreadnought. She first patrolled off the Shetland islands, and later off England’s east coast. She was involved in many armed encounters with U-boats, and Allum’s leadership and courage resulted in him being mentioned in dispatches. Viola is one of only four surviving British vessels that saw action in the Great War.

In peacetime, she was sold to Norwegian owners and renamed Kapduen, and then within a few years was converted into a whaler and renamed Dias. Her whaling involved voyages to the African coast. In 1927, she was sold to Compania Argentina de Pesca Sociedad Anonima – known as Pesca. The company operated from Grytviken, South Georgia and used her for taking elephant seals. Pesca sold out to British firm Albion Star in 1960. By 1964-65, the whaling station closed and Dias, together with the vessels Petrel and Albatros, was mothballed.

Viola/Dias was still there in 1982 when some Argentine scrap metal merchants landed with the aim of cutting up the ships. They then hoisted their country’s flag and triggered a war, making Viola arguably the only vessel to have seen action in the Great War and the Falklands.

Distinguished maritime historian Dr Robb Robinson found that luck played a part in his telling of Viola’s story. In a local radio broadcast, he spoke of a former Viola skipper whose life was as colourful as it was courageous. George William Tharratt – whose birth name was the grandiose-sounding Green Willows Tharratt – commanded Viola from 1912.

He joined the Royal Naval Reserve in 1914 aged 48, and served on other requisitioned vessels out of Newhaven. In 1919, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for services to minesweeping.

But Tharratt was also a bigamist and a philanderer. In 1893, he had bigamously married Elizabeth Ellis, a widow with six sons. And just weeks before getting his medal, he was cited as correspondent in a divorce case by petty officer Frank Bailey. George had been living with Bailey’s wife, who had a son by him – but the scandal was seemingly overlooked.

In the 1920s, Tharratt returned to Hull. He died in 1928 and was buried in a pauper’s grave.

Listening to Robb Robinson’s broadcast in 2014 was Tharratt’s then 97-year-old son, Eric. Later, the historian met with Eric, who told him more about his father – but not before Eric had learned some things too.

Robb said: “I never imagined that I would ever have to tell a 97-year-old man that his mum and dad were not ever married. He was fine with the news, and pleased that his father’s life as a skipper was to be recognised.”

Eric told Robb how his mother had told her five children that one of them would have to go to an orphanage, because she could not afford to keep them. She selected the youngest, two-year-old Violet, but Eric insisted that he went, because he was nearly 12 and could leave after two years and earn an income to support the family as the new man of the house. At 14, Eric got farm work, and four years later joined the company Smith & Nephew, where he stayed until retirement.

Eric said he knew little of his father because he was at sea so often and for so long, but on occasion he had joined him onboard – once on a fishing trip, and again on a ship sent to Ostend to collect coal during the 1926 General Strike.

Robb’s passion for Viola’s story joined forces with a businessman’s nous and a politician’s persuasive powers to spark a mission to bring her home. The Viola Trust has spent tens of thousands of pounds preparing for the great task ahead. Surveys it has financed have shown that Viola is in great shape for her age, and that her steam engines are still intact. She can be moved home – but at an estimated cost of £1m. It will be necessary to put her into a giant frame and onto a heavy lifting ship for the voyage back.

But a further £2m will be needed to restore her and make her into a museum. It is hoped there will be funds from the Heritage Lottery Fund, given its current £27.4m investment across six years in Hull to mark its revival as Yorkshire’s maritime city.

First, there is a Catch 22 to overcome. Robb, who literally wrote the book on the subject, along with Shackleton scholar Ian Hart, said: “In order for Viola to qualify for aid from the lottery people, she would have to be on the historic ships register.

“To do that, she would have to be in British waters, which surprisingly does not include where she is presently.”

Robb is a passionate advocate for Viola, and has done lectures about her nationally and internationally. At one, he so impressed publisher Richard Wynne that he was offered a book deal in 2014 for Viola – The Life and Times of a Hull Trawler. While promoting that book, Robb’s eloquence paid off again.

Maritime salvage expert Paul Escreet, who owns Hessle-based tug owner and operator SMS Towage, said: “I saw in the local paper that there was a talk by Robb about his campaign to bring the Viola home.

“To be honest, I went along to see if there was a commercial opportunity, but Robb is such a persuasive speaker that I ended up offering to help.”

At a later lecture in Leith, Robb’s persuasion worked again, this time with the then Liberal Democrat MP Sir Menzies Campbell. He invited Robb to make a presentation at the House of Commons.

That was how Alan Johnson got involved. The former Labour home secretary and ex-Hull West and Hessle MP became the Viola Trust’s patron. He was joined by local shipping owner Andrew Marr, ex-University of Hull vice-chancellor David Drewery, local maritime lawyer Dominic Ward, accountant Chris Try and Vice-Admiral Nick Lambert.

Alan Johnson said: “Since the government of South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands gave us permission in 2017 to bring the Viola home, we’ve been focused on the vital first-stage funding. I am confident we will get the remainder later.

“Hull City Council has been successful in securing a lottery grant for its big maritime heritage project. Viola can be its jewel in the crown and occupy one of the three berths being prepared by the project.

“One is for the last sidewinder turned museum ship Arctic Corsair, another is for the refurbished Spurn Light Ship, on the Marina, and the third berth is Viola’s. There’s a great will to raise the funds, and a lot has been achieved.

“Lots of folk, from businesspeople to ordinary members of the public, have come forward.”

Paul Escreet added: “I’ve had one businessman tell me that if we get her home he will give us £10,000 a year for 10 years. And recently, I received a cheque for £1,000 from a woman whose holiday was cancelled due to Covid, so she decided to support us.”

Getting the Viola home will not only boost tourism and save an important piece of maritime history, but also provide jobs and training. The Viola Trust and Humberside Engineering Training Association plan to have young people develop their skills with her restoration.

Alan Johnson added: “We have world-renowned salvage and towage experts right here in my former constituency in the heart of the old fishing community, and many dedicated people giving their expertise and support. But we need to land that one big fish to get us on our way home. So if there are any maritime philanthropists out there, please come forward.”

The final word on bringing Viola home should be from Eric Tharratt, the son of her former skipper. Now 103, Eric still lives in West Hull and supports the Viola Trust. He recently signed calendars created by a local artist at a fundraiser.

He said: “She is a big part of our history, and her coming home will also show the world that my father was more than just a man in a pauper’s grave.”

Photographs by kind permission of Lodestar Books, Dr Robb Robinson, the Tharratt family and the Viola Trust.

To donate to the Viola Trust, go to: violatrawler.net or write to: Paul Escreet, The Viola Trust, c/o SMS Towage, Ocean House, Livingstone Rd, Hessle, HU13 0EG.

Viola – The Life and Times of a Hull Steam Trawler by Robb Robinson and Ian Hart is available from Lodestar Books at: lodestarbooks.com/product/viola