The first sprats from the traditional localised niche fishery were landed at Mallaig earlier this month.

David Linkie looks back to a night aboard skipper Robert Summers’ Rebecca Jeneen in December 2012, pair-trawling for sprats with Willie John McLean’s Caralisa

01. Rebecca Jeneen finishes pumping 9t of sprats ashore at Mallaig.

02. Icy conditions in Glen Coe on the drive to Mallaig gave an early indication of favourable conditions for sprats to shoal up some 12 hours later.

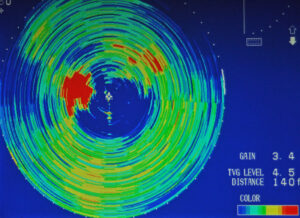

03. Hunting down the first decent mark of sprats, after some nine hours of searching and steaming.

04. Crewmen on Caralisa’s quarter prepare to pass their end over to their colleagues on Rebecca Jeneen.

05. Caralisa starts to pull away from Rebecca Jeneen.

06. Caralisa running off 75 fathoms of wire.

07. Skipper Robert Summers keeps a watchful eye on the sonar and sounder displays while regularly speaking to Willie John McLean.

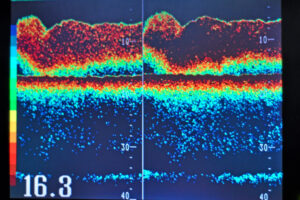

08. Towing over a promising mark.

09. Starting to haul the midwater trawl on Caralisa.

10. Using the block to dry up the trawl and run the sprats down into the bag.

11. Taking the first lift of the night aboard Caralisa.

12. Standing by to shoot the midwater trawl off Rebecca Jeneen’s quarter.

13. Running the wings over the transom rail.

14. Caralisa moves in to pick up the end.

15. Passing the end over.

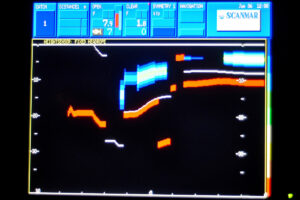

16. Securing the bottom sweep on Caralisa.

17. The Scanmar RX 400 net monitor starts to show fish entering the trawl.

18. Hauling the midwater trawl aboard Rebecca Jeneen.

19. Using the dog rope to bring the bag alongside.

20. The first lift of the night is taken aboard Rebecca Jeneen.

21. Lowering another lift of sprats into the hopper.

For more than 50 years, a seasonal end-of-year sprat fishery in West Highland sea lochs has provided an important alternative fishery for a small number of local prawn trawlers at Mallaig. Often fishing in just a few fathoms of water tight to rocky shorelines, sprat fishing can vary considerably from one night to the next, with skippers relying heavily on a lifetime’s knowledge of local conditions in order to return to harbour with a viable night’s work onboard.

Mallaig skippers Robert Summers and Willie John McLean have engaged in this West Highland sprat fishery for nearly 30 years – although the traditional fishery can be traced back even further, to days when the majority of boats taking part were west coast ring-netters rather than pair-trawlers.

An anticipated text – sent at 7am as Caralisa OB 956 and Rebecca Jeneen OB 38 were underway to land at Mallaig after a long but ultimately worthwhile night – signalled the green light to drive the 300 miles to Mallaig.

Several inches of fresh snow, together with sub-zero temperatures, a ridge of high pressure and clear blue skies, ensured that Rannoch Moor and Glen Coe were looking their majestic and spectacular best on either side of the A82 between Crianlarich and Ballachulish. With temperatures forecast to drop to -6°C overnight, prospects for the sprat fishery that night were looking favourable, given the often-quoted assertion that hard frosts encourage sprats to come together more.

Nine hours later, skipper Robert Summers eased Rebecca Jeneen out of the deepwater basin at Mallaig before setting a westerly course across the Sound of Sleat towards the southern end of the Isle of Skye and Cuillin Sound.

As was often the case, skippers Willie John McLean and Robert Summers had fished mainly in the Mull sea lochs – some seven hours’ steaming time away – since putting their midwater sprat trawls aboard in mid-November. For whatever reason, the notoriously fickle sprats had become more widespread recently, with more marks being located in sea lochs like Loch Nan Uamh on the mainland, considerably closer to harbour.

Sprats have traditionally shoaled in the inshore waters of the Minch, from the Isle of Mull north towards the Isle of Skye, from early October onwards, when – after feeding all summer in deeper water – they have a high fat content. Sprats usually only swim close to the shore when the water temperature starts to drop, and in particular when their stomachs empty after some hard frosts. This is when sprats reach the high quality standard required by a very discerning canning market.

After the customary weekend break, rather than returning south to the Isle of Mull, Caralisa and Rebecca Jeneen had taken good catches fairly early on the Sunday night, as a result of which the pair-team were back alongside at Mallaig by 2am. With the fish more widely spread out the following night and proving difficult to catch in bright moonlight, the skippers decided it was time for another change of tactics and location.

The highly appetising aroma of roast pork had been drifting up from the galley since departing Mallaig, so with a generous selection of vegetables served up by Jamie Mather, the five-man crew enjoyed a fine meal in readiness for the potentially long night that lay ahead.

Together with the second Mallaig pair-team of Margaret Ann II OB 198 and Ocean Hunter SY 503, Rebecca Jeneen and Caralisa spent two hours looking for signs of sprats in the vicinity of lochs Eishort, Slapin and Scavaig, as well as the Sound of Soay. Although Rebecca Jeneen’s Furuno CH 250 BB 360° 60kHz searchlight sonar indicated some signs of life, the fish were widely dispersed and swimming very quickly.

Rather than spend all night waiting for the fish to possibly come together and firm up, the skippers made the decision to spend the next three hours steaming southeast past Rum and Eigg towards the Sound of Arisaig and the northern shore of the Ardnamurchan peninsula.

Searching began again shortly before midnight, with the pair-trawlers sometimes splitting several miles apart while covering a wide area of Loch Nan Uamh, including around the islands of An Glas-eilean and Sgeil an Eididh south towards Ockle Point, Ardtoe and Kentra Bay.

With sprats usually only occasionally caught in daylight, when they come off the bottom in the deeper water of the Minch, the clock was constantly ticking, as although some small marks had been seen and recorded on the Trax plotter for possible reference later in the night, the crews had still not donned their deck gear after 3.30am.

This situation changed when skipper Willie John McLean reported more encouraging signs of fish fairly close into the shore near Ockle Point in 14 fathoms of water.

As a result, Caralisa’s net had been shot, with the wings hanging from the trawl gallows, by the time skipper Robert Summers closed Rebecca Jeneen up to Caralisa’s starboard quarter to enable the end to be passed aboard.

After the connectors were clipped in, the two boats started to pull away from each other as the sweeps were released, followed by 16mm-diameter Bridon Dyform wire from the North Sea Winches GF 200 three-drum winch (15t) situated between Rebecca Jeneen’s deck casing and the transom. The pair-trawlers worked 12 fathoms of 18mm-diameter combination sweep to the top wire and 15-fathom sweeps on the bottom wire, to which a 500kg chain towing clump was attached.

With 75 fathoms of wire shot off the outer drums, the pair-trawlers began towing 0.6 of a mile apart towards the mark. The pair-team were towing at 2.9 knots, with Rebecca Jeneen’s Caterpillar 3408C-TA main engine running at 1,225rpm.

As inside boat, Caralisa was already less than 100 yards from the shore when Willie John McLean reported that the fish were inside him. Following a slight course alteration, Rebecca Jeneen began to pick up the same mark. Tension in the wheelhouses was heightened by the fact that one of the flashing lights on a beacon indicating a mussel lay was not functioning, so the skippers were constantly trying to locate it in the darkness and occasional snow flurries, at the same time as trying to concentrate on the mark and the depth of their net.

A few minutes later, Rebecca Jeneen’s JRC JF130 dual-frequency colour sounder, operating on 28kHz and 50kHz, started to show sprats from 2.5 fathoms under the transducer to the bottom in 14 fathoms. Although the boats continued carrying the mark on their sounders, a considerable period of time elapsed before the first fish appeared at the net. Robert Summers explained that this was typical of the 2012 fishery, with the sprats proving to be fast-moving and difficult to catch.

With the boats constantly edging in to the shore in an attempt to chase the fish down, the Scanmar net monitor gradually began to indicate increasing quantities of fish entering the trawl. Having towed for some 15 minutes, the decision was taken to haul rather than turn for a second run.

In order to create sufficient sea room for bagging to take place, the team towed away from the shore and up through the wind before coming together to pass the end back to Caralisa.

Five minutes later, the first of what turned out to be nine lifts of sprats was lifted aboard Caralisa, before the codend was dropped back over the port side and the net dried up with the powerblock before the next lift was quickly taken forward.

Although this was a welcome start, the skippers expressed surprise that – having towed through a mark about a quarter of a mile long, which returned mainly deeper shades of red on the JRC sounder – it yielded only 8t of fish, which were bagged in less than 15 minutes. In previous years, a similar density of fish would probably have resulted in almost twice as much fish being taken aboard. The main reason for this difference was thought to lie with the higher energy levels that sprats showed towards the end of the fishery, when a large percentage of fish were very much alive when released into the hopper, compared to the usual scenario in previous years when nearly all fish were dead before being released from the codend.

As a result of skipper Robert Summers quickly locating another promising mark within a mile of the first haul, the powerblock was used to hoist the codend above Rebecca Jeneen’s transom in preparation for shooting 25 minutes after Caralisa had finished bagging.

Shot cleanly off the deck over Rebecca Jeneen’s transom into the darkness astern, the midwater trawl was a well-used Silver Gem, which over the years had been lengthened by Boris Nets. With 32in and 48in meshes in the wings, the 28-fathom trawl typically gave an opening of between eight and a half and nine fathoms.

Skipper Willie John McLean brought Caralisa close in to Rebecca Jeneen’s port side with the ease and skill associated with years of similar manoeuvres – which were further reflected by the speed at which the ends were passed over and the trawl was made all square, some two fathom off the bottom.

Although showing a similar density of fish and location in the water column to the first mark, the second was considerably shorter. Aware that the fish were again proving to be extremely flighty, and therefore were not tightly packed, the skippers agreed to turn back for a second look at the mark, which eventually led to the Scanmar RX 400 net monitor showing more fish falling back into the net under the headline transducer.

Shortly before 5.30am and 25 minutes after shooting away, the pair-trawlers came together again. The powerblock was then lowered to pick up the wings, as the net was quickly hauled down onto Rebecca Jeneen’s quarter, after the dog rope had been spooled onto the middle drum of the trawl winch.

Robert Summers’ earlier observation about a large proportion of catches coming aboard alive was immediately borne out when the first lift of clean sprats was released into the hopper. An enclosed chute allowing gravity-fed sprats to move continually from the hopper directly to the fishroom ensured that bagging was an efficient and continuous process. Not a single fish touched the deck or human hand as the flow of sprats into the fishroom – where five full-height ponds had been erected for the duration of the sprat fishery – was constantly monitored.

A total of just under 9t meant that the second tow closely matched the first. However, it also meant that with less than 90 minutes until first light, the pair-team had only half of its quota for the night – set each afternoon in line with market requirements – onboard.

After deciding to split up in order to revisit some areas where potentially fishable marks had been plotted earlier in the night, the pair-trawlers spent most of the next hour searching, before Willie John McLean called Robert Summers back towards Ardtoe Point.

As Caralisa and Rebecca Jeneen closed down on the mark after shooting to the west of it, the fish quickly scooted ever further into the shore. Secure in the knowledge that relatively deep water prevailed right up to the cliffs – the tops of which were gradually becoming discernible against a slowly greying sky, as dawn started to appear over snow-topped mountains – inside skipper Robert Summers edged in to within 25 yards of the shore, with the sounder showing nine fathoms of water. Although clearing the bottom by little more than a fathom, the skippers were not unduly worried about damaging the net, as they were moving along well-proven prawn tows, where they knew they were towing over muddy bottom clear of any potential fasteners.

Again opting to double back on the mark, which resulted in Caralisa becoming inside boat, the third tow of the night ended with the boats moving clear of the shore shortly after fish stopped entering the midwater trawl. The subsequent bagging added a further 6t to Caralisa’s tally.

More in hope than expectation, the boats steamed west towards Ardnamurchan Point, to check whether another mark, seen while steaming across from Skye, had come together, as can occasionally happen with daylight in the deeper water. However, with neither boat seeing any signs of fish after 15 minutes, the anticipated course alteration was made to steam north to Mallaig, some 18 miles distant.

Although Caralisa returned to harbour first, having broken a few crown meshes during the last haul, skipper Willie John McLean opted to mend his net on the pier, leaving the landing berth clear for Rebecca Jeneen. On passing the fish pipe down into the only pond in use, the sprats were quickly delivered ashore into bins via an Iras vacuum pump. With a long line of bins already put in place by shore workers on the quay, Rebecca Jeneen’s sprats were quickly delivered onto a layer of ice. Several more shovelfuls of flake ice were then placed on top of the fish, before the bins were doubled up by a forklift and loaded into the back of a waiting Nor-Sea articulated truck, for delivery to the International Fish Canners factory in Fraserburgh.

While the intention had been to spend the following night on Caralisa, a forecast of heavy snow for the West Highlands the following morning meant that common sense had to prevail – so within 30 minutes of Rebecca Jeneen berthing, the 300-mile return drive from Mallaig to northeast England began.

Rather than risk another night of sporadic fishing and possible frustration, skippers Willie John McLean and Robert Summers left Mallaig almost immediately after Caralisa had taken her net back onboard and landed, to steam some 50 miles south to Mull. The other pair-team of Margaret Ann II and Ocean Hunter had already set course for Mull before dawn, after finding the fish too fast-swimming and difficult to catch in the Skye lochs the previous night.

The ever-unpredictable nature of inshore sprat fishing was highlighted later that night, on receiving a text from Robert Summers saying that Rebecca Jeneen had 20t aboard by 8pm, after a single short tow.

Rebecca Jeneen and Caralisa

Skipper Robert Summers took delivery of the 16.5m steel-hulled twin-rig trawler Rebecca Jeneen OB 38 in November 2008. Built by MMS, Hull to plans drawn up by Ian Paton of SC McAllister & Co Ltd, Rebecca Jeneen was specifically designed for working twin-rig prawn hopper trawls, while also providing the flexibility to engage in the well-established winter sprat fishery.

A Caterpillar 3408C-TA main engine (355kW @ 1,800rpm) drives a 1,750mm-diameter four-bladed Kort propeller housed in a matching Kort propulsion nozzle through a Twin Disc 7.04:1 reduction gearbox. The hydraulics run off a Cummins 6CTA8.3 auxiliary engine (163kW @ 1,500rpm), which also runs a Stamford 60kVA 415/3/50 generator. An identical 60kVA second generator is driven by a 77kW Cummins 6BT5.9-D(M) auxiliary engine.

Rebecca Jeneen replaced skipper Robert Summers’ previous boat Ocean Trust OB 38, which he bought from Peterhead in 2001. Ocean Trust PD 127 was built by Macduff Boatbuilding & Engineering Co Ltd in 1982 as the whitefish trawler Osprey BF 500 for Charles Milne of Whitehills.

Caralisa OB 956 was bought by skipper Willie John McLean as Ardgour VI KY 100 from Pittenweem skipper William Gourlay in 2000 to replace another Miller’s-built boat, the 54ft Alisa OB 26.

The 17.6m wooden-hulled Caralisa was launched into St Monans harbour in 1975 by James N Miller & Son as the seiner/trawler Constant Hope II KY 100 for William Gray and Peter Jack of Pittenweem. Following her arrival at Mallaig, Caralisa was subsequently fitted with a new wheelhouse and a 272kW Cummins K19-M main engine.

After fishing prawns and sprats from Mallaig for 19 years, the original Caralisa was replaced 18 months ago, when father and son skippers Willie John and Aaron McLean bought the Fraserburgh twin-rig trawler El-Shaddai FR 285 from skipper David Nicol.

This vessel was built by Gerrard Bros of Arbroath in 1987 as Ephraim FR 3 for Fraserburgh skipper Michael Watt. The following year, Ephraim was bought by John Watt of Fraserburgh and renamed Excel FR 3. A further change of Fraserburgh ownership took place in 1999 when the trawler was renamed El-Shaddai by skipper David Nicol.

West Highland sprats canned in Fraserburgh for global retail sales

Nearly all of the West Highland sprats landed at Mallaig in the five- to six-week autumn fishery are destined for niche retail sales nationally and globally, after being processed by International Fish Canners (Scotland) Ltd (IFCS).

Established in 1979, since which time the company has primarily focused on the production of mackerel fillets and brisling sardines, together with other quality seafood products under private label agreements, IFCS is the only manufacturer of canned fish in the UK, taking particular pride in using sauces made in-house from natural and preservative-free ingredients.

Marketed as brisling sardines or Scottish sardines outwith Europe, but as sild and skippers in the UK, the fish are processed into a wide variety of ready-to-eat recipes for well-known companies such as John West. Depending on the intended sales outlets, sprats can be light-smoked, kiln-smoked or left natural.

On arrival at the IFCS factory in Fraserburgh, within six hours of being pumped ashore into bins and iced on the quayside at Mallaig, sprats are placed into a dedicated chilled holding area until they are transferred into the factory for processing.

After being headed, the fish are hand-packed by skilled operatives in either single or double layers in 110g tins, prior to automated delivery to an oven where they are cooked at a temperature of 130°C for 40 minutes.

A wide range of sauces, oils and brine, including tomato, sunflower, spring water and low-salt, are then added to meet the precise requirements of the retail sales outlets in the destination country. Ring-pull lids are added to seal the contents, and the cans then enter retorts for secondary cooking at a temperature of 112°C for 61 minutes.

After being left to cool for 24 hours, every tin is electronically scanned to verify a perfect seam, before being packed in retail boxes ready for display in supermarkets throughout the world, including in Australia, Canada, Japan, South Africa, the USA and the UK.

Apart from manually packing the fish into cans, the entire process is automated to meet exacting standards, including every tin being aligned to ensure that the ring-pulls have exactly the same orientation.

Some 10t of sprats are handled each day, allowing up to 60,000 cans of ready-to-eat product with a minimum shelf life of three years to be processed daily.