Ashore for Christmas? For Hull trawlermen, Yuletide trips were often an obligation – and were fraught with added danger.

By Alec Gill

Christmas was a time of conflict within Hull’s trawling industry. The clash was between love and money.

Trawlermen loved to be at home over the festive season, living it up with their family and friends. The trawler owners, however, wanted their vessels at sea in order to land fish on the market for early January. The price of fish was always extremely high around 1 January, because all Scottish fishing ports were closed for the Hogmanay celebrations north of the border.

The ships’ runners bore the brunt of this conflict of interests. They were employed to crew the ships (each firm had its own runner). It was a difficult job at the best of times, but especially during the run-up to Christmas. They did their job by fair means or foul.

Different strategies were used to get the ships away. One was to sign men who had been on a ‘walkabout’ or were ‘blackballed’. A man who had been disciplined by the owners would be keen to ‘get shipped up’ and work his way back into the industry. Christmas was his best chance.

Another devious method, when scraping the bottom of the barrel, was to visit premises such as the Flying Angel Club (where Merchant Navy seamen lodged when out of a ship) or the William Booth Hostel, run by the Salvation Army for single homeless men, commonly known as ‘down and outs’. The experience of the men signed on thus usually left something to be desired!

A third supply of crewmen was volunteers who had never been to sea before, but who had contacted the trawler firms to get a trip. Skipper Dickie Taylor told me: “They came from all over the country – in different shapes and sizes.” Other trawlermen remembered these irregulars as including dustbin men, miners, coalmen, a London cabbie, a lion tamer and an undertaker’s assistant from Perth.

Some were very seasick, as it was their first ever trip, whilst others refused to gut fish because they felt it was cruel. Many comical things happened because they did not know the job. Such crewmen were known in Hull’s Hessle Road fishing community as a ‘Christmas cracker crew’.

A fourth method of getting men aboard was to promote a crewman to a higher position on condition that he took a Christmas trip. A mate, for example, often got his first command as skipper during this period. This happened in the case of Jim Stephenson in 1934. He was suddenly given charge of the Edgar Wallace H 262 for a Christmas trip to fish off Bear Island, with a crew none of whom had sailed together before, and many of whom were not fully qualified to do the job. And teamwork is essential on a trawler!

The Edgar Wallace fished a successful trip – but then sank on 9 January, 1935 in the Humber estuary. The loss was not a direct result of there being a Christmas cracker crew onboard – nor was the young skipper at fault. But perhaps the loss of life – 15 of the 18 crew – might not have been so high had they been an experienced team of regular trawlermen.

The Edgar Wallace H 262, which sank on 9 January, 1935 in the Humber estuary after a Christmas trip to Bear Island.

The Hull trawler Orsino H 579 (pictured in the main image) fished the White Sea grounds over Christmas 1948. Abroad were a real ‘Christmas cracker crew’, and the trip was a fiasco from beginning to end. John Crimlis, the 18-year-old deckie learner, described it later as ‘a trip that lasted a lifetime’. He was biding his time on trawlers until he was due to join the Royal Navy in March the next year.

The 1931-built Orsino left St Andrew’s Fish Dock on 1 December. Hopes were high that she would be back well before the festivities began, the average trip being 21 days. Nevertheless, the Christmas turkey was loaded onboard, just in case.

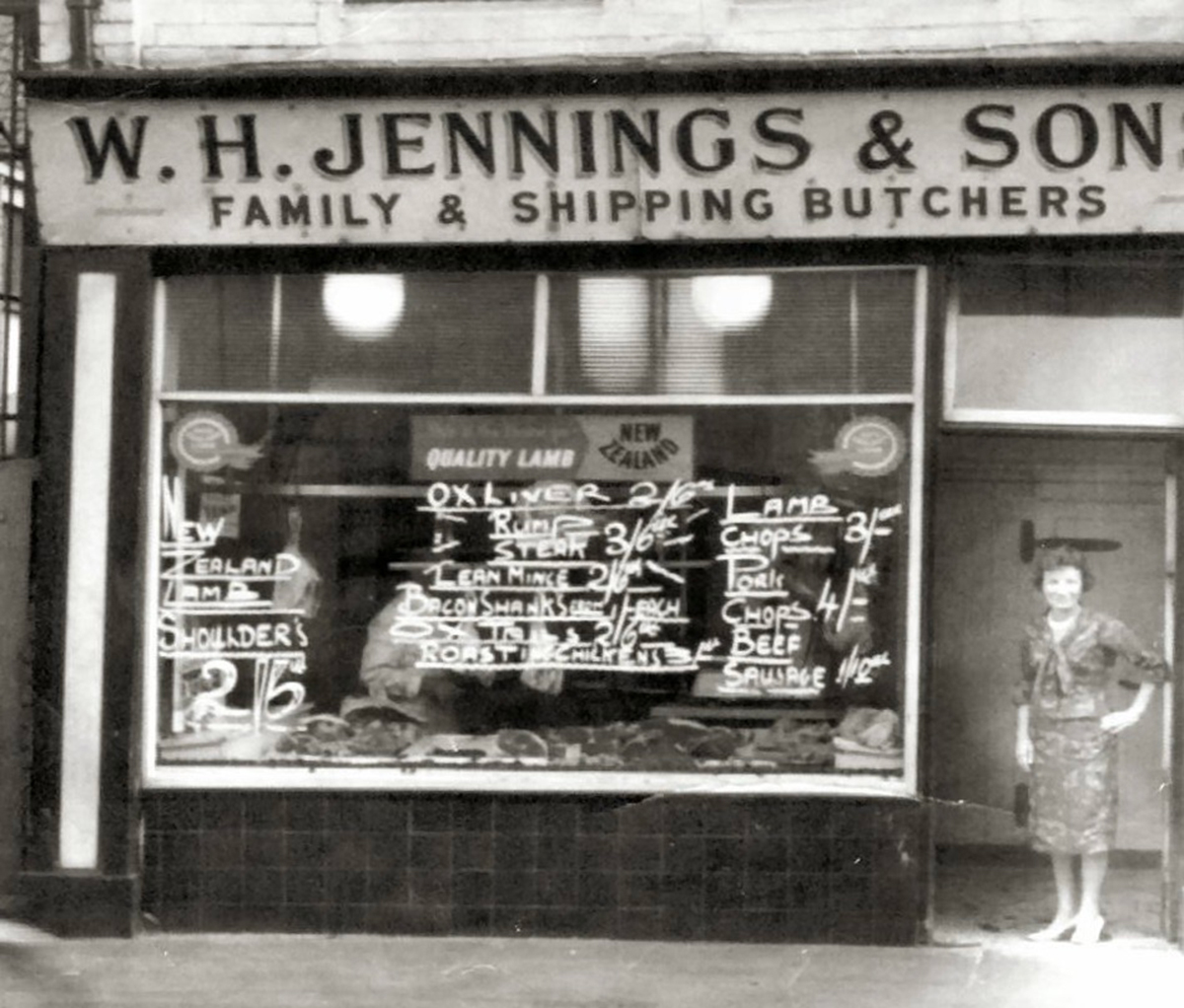

Jennings Butchers on Hessle Road usually supplied the turkeys for each trawler’s Christmas trip. This was a ritual every December, and the local paper often sent a photographer to the fish dock to record the handover of the big bird.

The new crew of the Orsino hit problems even before they arrived at the fishing grounds. The boiler blew its tubes off Norway. All power was lost, and she drifted out of control. Two fish baskets were hoisted up the foremast to signal to nearby ships that the trawler was adrift. At night, two red oil lamps replaced the baskets.

The loose end of the line to the lamps on the masthead should have been made fast to a cleat. Instead, an inexperienced crewman wound it around the winch drum. Compounding this blunder, the cock valve that powered the winch gear was mistakenly left open.

When the steam tubes were eventually repaired, the unattended winch drum slowly began to revolve of its own accord. The wire rope attached to the paraffin lamps pulled taut. The tension was such that the main mast was nearly snapped in half. Instead, the two lamps crashed down and made ‘a hell of a mess all over the deck’.

This was merely a prelude to the pandemonium. Nevertheless, there followed a ‘calm before the storm’. With the Orsino back under her own steam, she was soon fishing at the White Sea grounds. There, a strange fluke occurred in the weather conditions. Although Britain was in the grip of a savage winter with Arctic blizzards, the Orsino steamed into a spell of glorious sunshine. It was so warm the deckhands gutted fish in their shirt-sleeves.

They also had unbelievable luck with the fishing. Within four days they had around 1,200 kits aboard. This former Grimsby trawler (ex Solon GY 337) was not a large vessel – her total capacity was only around 2,000 kits. The men were in a jubilant mood, knowing that the fishrooms would soon be full. They worked hard, sure in the belief they would be home for Christmas with good settlings in their pockets. Spirits were so high that the Christmas fare was eaten early.

The skipper wired news of the splendid catches to vessel owner Hellyer Brothers in Hull, and eagerly suggested he steam home with the catch of headless fish (in the post-war period, the heads were tossed back into the sea so that more fish could be stored below). The mean-spirited order came back, however: “No. Stay out. Fill her up.”

The men were not happy with this command, but the skipper was in no position to challenge his bosses – he might not get command of another ship. Trawler owners often blackballed even their top skippers if they stepped out of line.

No sooner had they been told to continue fishing than the mild weather broke. ‘It just blew’, the crew recalled, in understated trawlermen’s terms. They were hit by a hurricane of storm force 11 or 12. All other trawlers in the vicinity hauled in their gear and ‘lay to’, dodging ‘head to wind’ to ride out the storm.

Not the Orsino. She continued to fish. But after the disappointment of not steaming home in time for Christmas, and then being ordered to shoot the trawl gear in dangerous conditions, the men refused to work and went below.

With the deckhands on strike, young deckie learner John Crimlis volunteered to go on watch with Mate Allenby – a close friend of the Crimlis family. It took both of them all their strength to hold the wheel steady as they battled to keep the trawler head to wind. Then a giant wave hit the 348t vessel full-on. John described it as ‘like a tram crashing into a brick wall’. Everything shuddered – even the ship’s funnel rocked. The ‘old man’ – a general nickname for any skipper – was in his berth when the wave hit, and shot up to the wheelhouse.

He was furious when he saw the pound boards – thick wooden planks that slotted into stanchions to stop fish swilling all over the deck – getting smashed to pieces as tons of water thumped down on the deck. Some boards were being washed through the scuppers into the raging sea. The skipper turned to the mate and said: “Joe, can’t you go down and save some of these boards?”

The mate was afraid to disobey in case he lost his job – so he went out to risk his life instead. Deckie John loyally went too. On the rolling deck, he managed to pick up one board and carry it for’ard to store under the whaleback. When John looked around, he saw Joe desperately struggling with a heavy board under each arm.

Just then, another enormous wave loomed over the 140ft trawler. John yelled out a warning as the mate tried to run toward the protection of the whaleback. The sea dropped inboard and gallons upon gallons of bitterly cold water smashed all around the deck.

Mate Allenby disappeared under the deafening torrent. When the spray and mist finally cleared, John saw him clinging to a bollard – but he still had the two deck boards gripped under his arms. During the storm, the small fo’c’sle funnel was completely washed away. Below, ‘it was like a lake with water sculling about in the deckhands’ quarters’. The mutineers had to go down aft in the mess deck to sleep on seats or wherever they could rest their heads until the water cleared away.

When the weather eased, the skipper was determined to follow the owners’ orders to ‘fill her up’ – despite the deckhands’ continued refusal to work. In their place, the trawl gear was shot away by the mate, bosun, wireless operator, cook and two engineers. Young deckie John was on watch in the wheelhouse with the skipper.

After a couple of hours, the trawl gear was hauled up. It was a good catch. The codend was winched out of the sea and held against the bag ropes to steady the load as the Orsino rolled and pitched in choppy waters. The skipper got down on deck to supervise the precious catch. As he gave orders, the bag ropes suddenly parted. The heavy codend swung inboard like a ball and chain, straight at the skipper. He went flying, and was lucky not to be killed.

His face was black and blue, and he was forced to spend the rest of this ‘endless’ voyage in his bunk. He insisted, however, that fishing continued.

Christmas came and went as the substitute ‘deckhands’ attempted to fish whenever there was a break in the rough weather. But the nets kept ripping apart, and the mate was not always around to fix them properly. With the Yuletide dinner already eaten, all that was left on Christmas Day was dry bread and spuds. Practically all the crew went down with diarrhoea.

It was a struggle, and took four long weeks, but the skipper was able to return to Hull with the Orsino’s fishrooms full. The men even missed out on the New Year celebrations, only landing on 1 January. But the cruel irony was that the majority of the catch was condemned as unfit for human consumption. It was carted around to the Hull Fish Meal factory on the south side of St Andrew’s Dock.

When fish was condemned as unfit for human consumption, it was dumped at Hull Fish Meal to be turned into various animal feed and vitamin products for cattle, pigs and poultry.

Had the Orsino returned when the initial request was made, its catch would have brought a good price for all concerned, and the men would have spent Christmas at home. As it was, the ship just managed to clear its expenses for the voyage – but there was no settling pay for the crewmen. All the deckhands who mutinied were later sent before a judge and fined.

The Orsino was not the only Hull ship with Christmas cracker problems. At least four other trawlers had trouble during that 1948-49 winter. The first was the Kingston Amber H 471, which left Hull on 8 December. Two days later, Skipper Jack Moore put into Lerwick with a defective boiler. Sadly, 18-year-old deckhand Ray Akrill suffocated to death during a fire in the crew’s quarters.

Nine of the crew then left the vessel; they were said to ‘have a certain attitude’ and to have claimed ‘that the trawler was an unlucky ship’. Four of them were later brought before the Hull magistrate, who fined them for ‘wilful disobedience to a lawful command’ from the skipper.

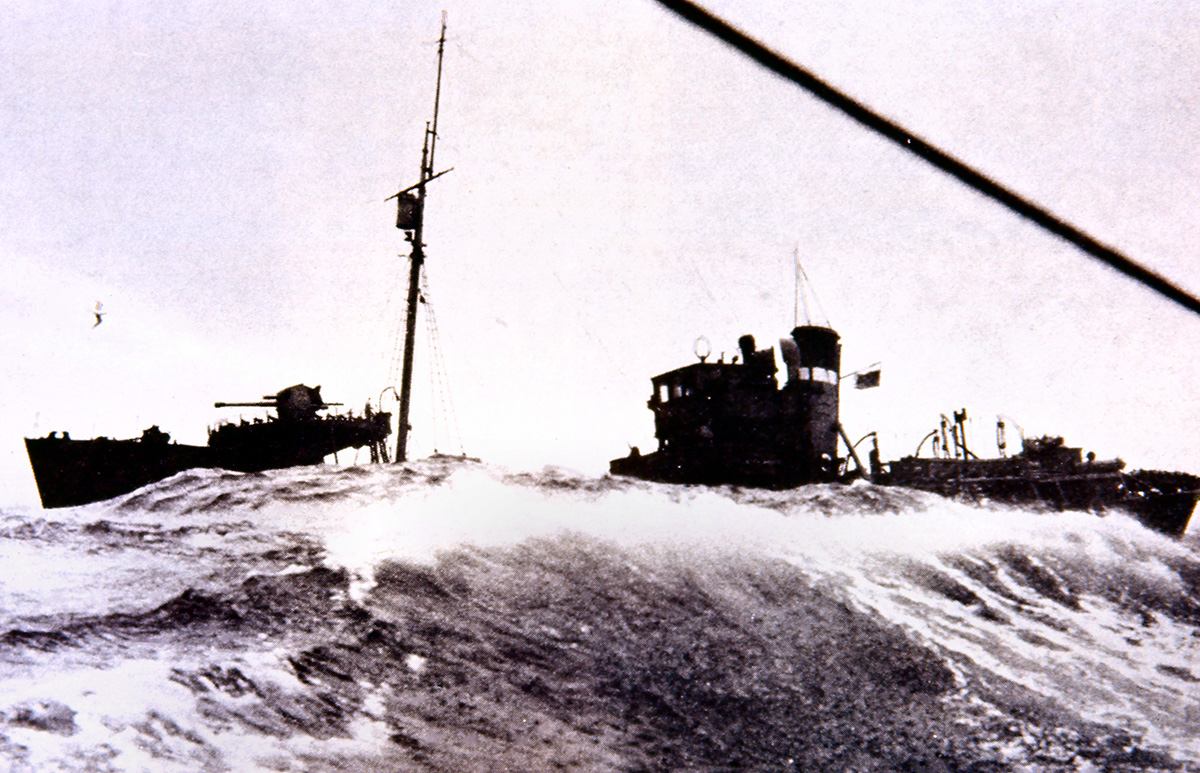

A fatality occurred aboard the Kingston Amber H 471 in December 1948 at the start of a Christmas trip – after which nine of the remaining crew refused to sail. This vessel was requisitioned by the Navy in September 1939 (as FY 211) as an anti-submarine trawler. Above her wheelhouse in this picture is the ASDIC deck to detect German U-boats.

The St Elstan H 484 ran aground on Boxing Day 1948 on the Norwegian coast. Her rudder was dislodged, and she had to be towed back to Hull from Bergen. When the 564t trawler berthed at the fish dock in February 1949, the Hull Daily Mail printed a photograph of the large rudder lashed to the deck.

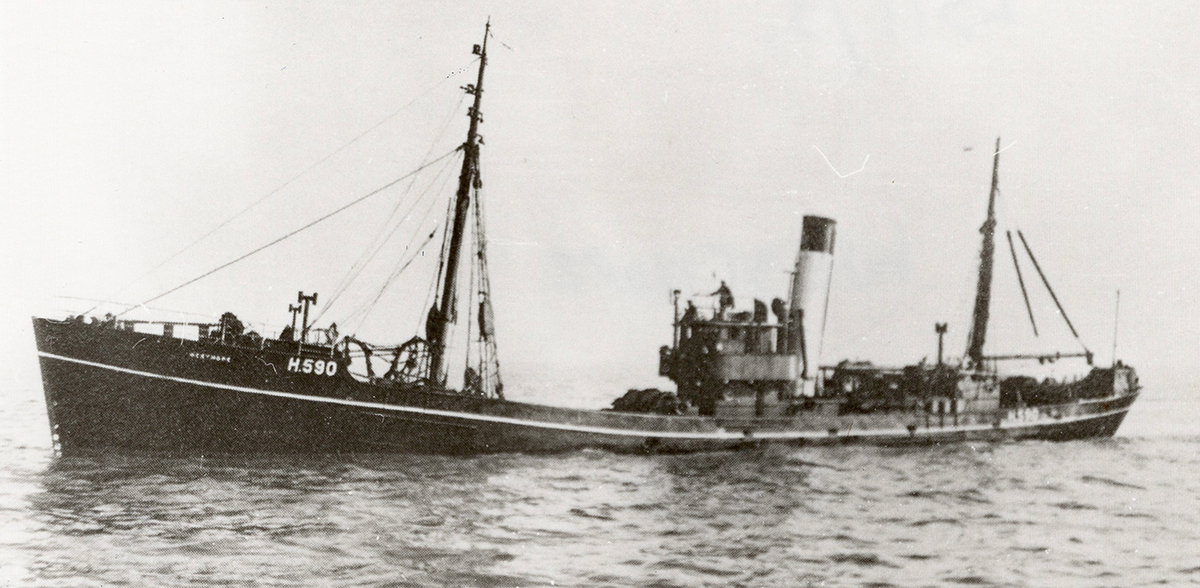

Westhope H 590 was only 50 miles out of Hull when the ship ‘heeled right over’. One of the crewmen had only just survived the loss of the Hull-based trawler Sargon GY 858, in which 11 men died when she was wrecked at Iceland on 1 December, 1948. In view of the high level of anxiety aboard the ship, Skipper Len Harrison decided to steam back to Hull.

Once back alongside, three of the crew refused to sail again. They believed the Westhope was ‘not fit to go to sea’. A ship surveyor was called in to give his OK, and tons of ice was dumped overboard to make the ship lighter. But they still refused to sail her. A magistrate found all three guilty of disobedience and they were fined £1 10s 6d each.

The Westhope H 590 was built in 1927, and was originally launched as the Kingston Onyx H 365. She was converted to anti-submarine work in April 1941. She then became the Moorsom GY 119 in 1946 for a short spell in Grimsby, before returning to Hull and becoming the Westhope in 1947. She was not scrapped until 1956 – not a bad maritime life, after nearly three decades of trawling.

Finally, there was a fire aboard the Bardia H 302 at the White Sea grounds. The wireless operator sent out the urgent message: “Making for Namsos owing to main bunkers on fire… escorted by trawler Bizerta.” Both vessels belonged to Hull Merchants Amalgamated Trawlers Ltd. There was, however, no real damage, no one was injured, and the trawler was able to continue fishing.

All in all, it was a right year for the Christmas cracker crews.

Bardia H 302 had a fire in her main bunkers at the White Sea grounds at Christmas 1948. She was another Hull trawler that had been taken over by the Admiralty between 1940 and 1945 for mine-sweeping duties, as FY 1809.

This story was taken from the latest issue of Fishing News. For more up-to-date and in-depth reports on the UK and Irish commercial fishing sector, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.30 here.

Sign up to Fishing News’ FREE e-newsletter here.