John Worrall reports on a seafood icon in an uncertain world

Let’s talk local heritage: Cromer crabs, a happy bit of alliteration that sticks in the mind to conjure visions of wide beaches, seaside fun and wholesome seaside fare, with or without mayonnaise.

And long has it done so, ever since the railway reached the Norfolk town in 1877. And longer ago than that, back in 1724, Daniel Defoe mentioned Cromer sea fare reaching London (his particular reference was to lobsters, but – hard shell, claws… same sort of thing, really). But the railway improved distribution, and brought visitors to taste it at source. The word spread.

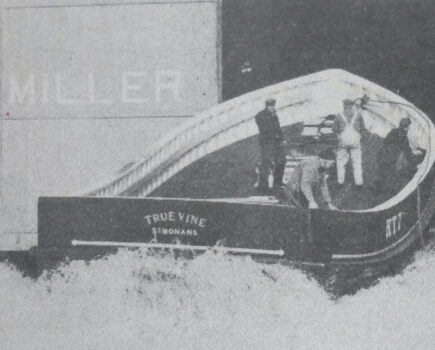

In the early 1990s, traditional wooden crabbers…

And the taste, which is the essence, is an environmental thing, hinging on conditions on the Cromer shoal chalk bed just offshore, which stretches along the coast for 20 miles from Weybourne, west of Cromer, to Happisburgh, to the east – 125 square miles of special ground that breeds the small and particularly sweet brown crabs of Cromer fame.

Not that crabs and lobsters were always North Norfolk’s main fishing event. A few hundred years ago, the creekside settlements of the central part were sending boats all the way to Iceland for the summer to catch cod and ling, which they salted and brought back for sale to the cities, particularly London. When wet holds – a Dutch invention – came in, they brought back live products, although it was still mainly for the cities, because the small North Norfolk settlements stayed small, with thinly populated farming hinterlands. And while boats got bigger, the creeks didn’t – in fact, some got smaller through land-grabbing by local gentry – and fishing retreated to coastal waters.

In the 19th century, there was still some fin-fishing, if mentions of ice merchants in local directories are anything to go by, and sporadic netting and lining continued into the 20th century. But for a few generations now, it’s been mainly potting. The surviving wooden boating heritage is all crabbers and whelkers.

The boats working the chalk these days are mostly beach-launched and single-handed – that latter point raising, as elsewhere, the question of continuity, because few lads have crewing options – and, with thinning prospects, fewer want them – to learn the job and the ground.

And that’s a fairly recent thing. Until the early 1990s, beach boats were wooden, two- or three-handed double-enders, built by a handful of local builders. But then, GRP single-handers began to appear – also locally built, as it happens – which were lighter on handling and maintenance. They could work fewer pots, but more pots per man, and with fewer lads wanting the life, the fleet’s direction was set.

“For a few generations now, it’s been mainly potting. The surviving wooden boating heritage is all crabbers and whelkers”

The fleet also goes after whelks again. These had faded from the scene in the last century, partly in the 1960s through the loss of the rail connections which had taken them to the Midlands markets, and partly through stock damage by Tributyltin (TBT) in anti-fouling paint. But TBT was banned, and whelks have returned, to provide a fall-back fishery that sells mainly to Korea.

… still made up most of the fleet at Cromer…

But still, in the public perception, North Norfolk fishing is really about crabs, which anyway account for well over three-quarters of the combined beach-launchers’ crab/lobster catch, if only marginally more than half by value.

It’s the same brown crab, Cancer pagurus, that is found from Scandinavia to Portugal, but the UK and French coasts have much of the action. And in the southern North Sea, it’s the breeding and growth pattern that is key to the Cromer crab taste.

Mating peaks in summer when the female has moulted, with spawning in late autumn or early winter, for which females scoop a hollow in soft sand or gravel in which to settle, to ensure that the eggs – up to three million for the biggest females – attach to the limbs. Once berried, females don’t feed again until the larvae hatch between May and July, the larvae then spending about five weeks in the plankton, drifting far and wide, before survivors settle in coastal shallows. They take four or five years to reach commercial size.

But here’s where the distinctive Cromer taste comes in. Studies of the North Sea crab fishery in the 1960s, and others on the English Channel fishery in 1968-1976, found that North Norfolk crabs grow more slowly, and are smaller on reaching maturity, than those in the Channel.

The size difference is quite marked. Channel males occasionally reach a 250mm carapace width, whereas in the southern North Sea, 180mm is big. Similarly, Channel females range between 160mm and 175mm, compared to an average of 128mm in the southern North Sea – smaller even than in the northern North Sea, where the average is around 150mm, and 200mm males are not uncommon. Large specimens are more common in deeper waters offshore.

In recognition of all that, when the crab minimum landing size (MLS) was revised in 1986, having been 115mm nationally since 1951 (and before that, 108mm, fixed all the way back in 1877), the southern North Sea was given a derogation by the European Community to retain the 115mm MLS, while elsewhere it was increased to between 130mm and 160mm.

… but within a couple of decades, they had been replaced by GRP skiffs – and a couple of catamarans – except that one (left) kept working, and still does.

There is a further element in the equation, which is that tagging studies have shown that mature females in the North Sea tend to migrate offshore to deeper water, and northwards along the coast to Yorkshire and beyond, which is against the residual current. A similar phenomenon occurs in the Channel, where females move west, again broadly against the current. The thinking is that this allows the tiny fraction of surviving larvae to settle back close to the point of origin. Some males also travel, but randomly and to a varying extent, with no particular direction.

The 115mm MLS suits the North Norfolk fishery, because although the big processors pay more for bigger crabs, smaller crabs predominate on the chalk, because bigger specimens tend to head for deeper water, including those females heading off to spawn in suitably soft ground. Added to which, visitors to North Norfolk are happy to have their Cromer crabs more bite-sized – enough for one helping – and for boats that do their own processing, the visitor market is crucial.

The peak of the North Norfolk crab season runs from March – weather permitting – to July, by which time females are moulting and males are mating, and crabs generally quieten down; late summer is more about lobsters. But the boats continue to work for as long as the weather will allow, picking up what they can.

But it is the way of the regulatory world these days that every activity has to be scrutinised.

Under the Marine and Coastal Access Act, the IFCAs have to ensure sustainable exploitation of resources, and achieve good environmental status in all EU marine waters by 2020, at present according to the Marine Strategy Framework Directive of 2008. Brexit may or may not change this, but in any case, nothing will change quickly.

To add to the regulatory equation, the Cromer shoal chalk bed was, in 2016, one of 23 sites in the second tranche of Marine Conservation Zone designations.

Whether the crab fishery has a particular exploitation problem isn’t clear. The most recent CEFAS crab stock assessment – in 2017 – stated: “The spawning stock biomass of edible crab in the southern North Sea is approaching the recommended level for females, but remains low and around the minimum recommended level for males.” It goes on to say that the exploitation rate is ‘high’ – “Around the maximum reference point limit for both females and males.”

However, it acknowledges uncertainty. “Scientific data collection… is taken from a relatively small number of landings and then scaled up to represent the whole landings, a process which cannot be exactly correct, but should be broadly representative of the population as a whole.”

Cromer jack crab.

Meanwhile, an Eastern IFCA report in 2016 said: “Mortality estimates for C. pagurus specify high levels of exploitation for this species and indicate that growth overfishing is occurring. Despite this, there does not appear to be any significant impact on recruitment.”

That would seem to point to the female migration and the circulatory system in play, with larvae drifting from elsewhere to settle in the chalk, where they grow more slowly than other stocks to reach their smaller MLS, full of the renowned denser, sweeter meat. As they then grow on, they tend to move to deeper water beyond the reach of those beach-launched single-handers.

That, in turn, suggests that the bulk of crabs within the commercial-size biomass on the chalk are relatively transient and, having reached 115mm, might still be below any MLS applicable elsewhere when they begin to move off.

Catches each year vary – as anywhere – according to the larval settlement four or five years previously. The Eastern IFCA report noted that three previous years of particularly good crab catches had come with no apparent significant increase in effort, while lobster catches in the same gear remained fairly even.

Nevertheless, Eastern IFCA must keep a watching brief, and so it is holding an informal consultation on what might, or might not, need to be done on potting generally. The consultation runs until 1 October, and an online submission form can be found on its website at: bit.ly/2k3EHlk

One topic up for discussion is effort control, but as the consultation itself recognises, where and how to draw the line might be difficult. In any case, effort is already subject to the vagaries of the weather, particularly during those vital spring months. Last year, the Beast from the East in February, together with the Mini Beast in March, kept water temperatures down and, with crabs not stirring much at water temperatures below 8°C, no fishing was done until late April. There went half the peak season.

Even without those cold snaps, anything much above a three-foot swell more or less stops beach launching, and such conditions are by no means unusual on this coast, where spring easterlies are a regular feature – so regular, indeed, that in the late Middle Ages, the Hanseatic League relied on them to push their square-sailed cogs westwards from northern Germany on their annual trading voyages.

If it’s not the snow, it’s the wind and swell…

Another topic is escape gaps, but these are unlikely to be a particular problem, because they reduce time and effort in clearing the pots, and many fishermen already have them. The downside – if it is much of a downside at all these days – is the loss of velvet crabs, but after a brief few years after the turn of the century when velvets began to feature, the Beast and other cold snaps seem to have killed them off. Lots of dead ones were seen on the shoreline.

A more difficult suggestion is an increase in that 115mm MLS.

On the one hand, the big processors pay more for bigger crabs. On the other, the original idea of keeping 115mm back in 1986 was that crabs on the chalk grow more slowly, are smaller at maturity, and are smaller on average compared to other areas.

The idea behind this suggestion is to increase the spawning potential of the stock, with each crab given more time to reproduce, and to increase the number of larger individuals within the stock. An acknowledged downside is the initial losses in landed catch, ‘although this is considered to be a short-term impact’.

But the evidence seems to be that bigger crabs don’t tend to hang around anyway, females in particular moving off to hatch their eggs elsewhere, and thus spending a relatively short time within reach of the beach-launched boats before moving off. In which case, raising the MLS would risk a long-term – rather than short-term – reduction in the number of crabs available.

Potting has been going on along the North Norfolk coast for generations, and once upon a time, it was undertaken far more intensively than it is today. In the days of sail at the turn of the 20th century, there were four or five dozen boats working from Cromer beach, and reportedly more than that at Sheringham – and that was with an MLS of 108mm. And they were all making a living, albeit hauling manually and working fewer pots per boat.

… but summer can be pleasant.

Even in the late 1950s, well into the engine era, Cromer had a couple of dozen boats, and Sheringham 15. These days, there are barely three dozen in total working between Weybourne and Happisburgh, 14 of them from Cromer – a dozen single-handers and two catamarans – and just five now from Sheringham. The rest are in twos and threes from the villages up and down.

It continues as a low-impact fishery – local processing, few food miles, and almost no by-catch – feeding into its communities within a wider economy which is substantially seasonal and low-wage, and where property prices are fixed by money earned or inherited elsewhere, with which most local earners can’t compete.

But the core of the fishery is the small, sweet crab that has made its name. It grows slowly on the chalk but tends to move away as it grows on, and although there are certainly big crabs to be had, the bulk of the fishable stock is between the 115mm MLS and the 130mm minimum applicable elsewhere.

As the consultation itself notes, raising the MLS may have ‘a larger impact on vessels fishing closer inshore’, as there is the ‘potential that smaller crabs occupy inshore waters and then move further offshore when reaching a certain size, rather than staying to be caught next year’.

And that is the crucial point. Cromer crabs are caught close inshore, and whether or not limiting the fishery to fewer bigger crabs would actually do much to maintain a biomass replenished from elsewhere, it would certainly damage what’s left of the fleet, compounding recruitment problems and eroding business models. It would certainly diminish – and maybe even end – a piece of local heritage.