Des Pawson does knots.

He does all sorts of knots. In fact, there can’t be many knots he does not know. And ropework; he does sailors’ ropework in particular, which is where knotting is and, more particularly, was the key to plain sailing and survival.

It’s partly down to his uncle.

Des Pawson does knots – which, here in his workshop, make a boat fender…

Des Pawson said: “When I was seven, an uncle gave me a scouting book with knots in it, and these knots interested me, and I was able to tie them and I was hooked. I was in the Scouts right through to 21, and ropework was my interest. I would charge to make a Turk’s head woggle for other cubs, which meant I valued my skill from an early age, and that’s really how I’ve been able to make a living.”

He has indeed made a business out of it. You can’t sell a knot, but you can sell their stories and things made out of them.

Not that it’s an easy business to get tied up in, and in his early twenties, Des was working in the furniture department at Harrods. But that had two spin-offs: it made him good at dealing with people, and it was within a lunchtime walk of Captain Watts, the yacht chandlers in Mayfair. One day late in 1968, he walked along and showed the buyer a couple of bell ropes he’d made.

‘in 1989, the business had grown so much that either it or the day job had to go’

“They weren’t quite what he was looking for, but he described what he wanted – about seven inches long, with a thimble at the top – and I went away and made one, and took it back, and he said, ‘Oh, yes, that’s fine. I’ll give you an order.’ And he got out his order pad and wrote down ‘three’, and I thought, ‘Oh. I’ve done all this work, and I’m going to get an order for three.’ Because these things, at that time, were each taking about an hour and a quarter. But then he wrote ‘dozen’, which hit me exactly the opposite way. I was expecting perhaps half a dozen.

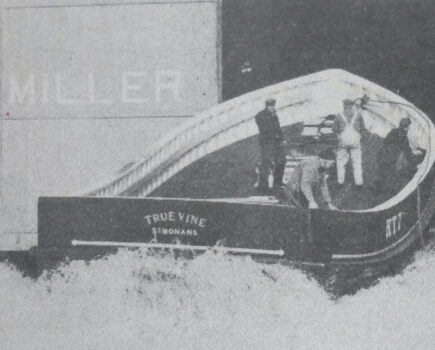

… and, on a larger scale, made a bow pudding for the Lucy Lavers lifeboat.

“So I had to work all over Christmas, because they wanted them for the London Boat Show in January. But that started me off on commercial production, rather than just the odd item.”

Des Pawson’s raw material, mostly braided nylon for that sort of thing, came through his soon-to-be father-in-law, who had connections in the wholesale haberdashery trade and could get picture cord. Des kept on producing stuff alongside the day job, upping production when the children came along and life got expensive.

But from the outset, he treated it as a business.

“I understood that people were interested in watching you work, and so during a tall ships rally on the Thames, I sat in a chandler’s window in St Katharine Docks doing ropework, and from that I sold a few things and picked up small commissions.

But it’s the museum which really articulates the passion.

“By then, I was making bell ropes for Nauticalia – a company making maritime-themed gifts, which had just started up – and as its business grew, so my production grew. I’d moved to East Anglia for a job with Ryman’s in their office furniture section, but we – my wife, Liz, and I – were working hard at home, spending holidays and weekends at boat shows, selling fenders, mats, bell ropes, key rings.

“And then, in 1989, the business had grown so much that either it or the day job had to go. And the day job went. We sold a stock range of fenders and bell ropes at boat shows, but we were regularly asked for bespoke items, because people might be able to buy coir (coconut fibre) rope items made in India, but they probably couldn’t find one to fit their boat in the way they wanted.

It has anything from sennit doormats – this one made onboard the cable-laying ship, SS Colonia, by Walter George Chivers in 1922. He died in 1974, and his family donated it to the museum…

“One of my specialities was wraparound rope fenders – we had developed a technique which stopped them drooping between fixing points – and I still make them. But we have never advertised. It’s been word of mouth. People might see you at a show, and three or four years later get in touch when they have a knotty problem,

… to a 1682 rope-making machine…

perhaps something for a film or for a boat, say a bowsprit net.”

One particularly interesting – and challenging – job involved the restored 1940 lifeboat Lucy Lavers, and the making of a new bow ‘pudding’ or fender.

“That was a nice job, because bow puddings go back to the early days of the RNLI. The North Norfolk charity Rescue Wooden Boats, which restored the Lucy Lavers, wanted a bow pudding, made as it would have been at the RNLI’s former Poole workshop.

‘We told our contacts worldwide about our museum, not necessarily expecting them to visit, but making the point that we were treating the subject seriously’

“I was lucky, because I’d previously been in touch with a man who’d worked there, and who’d told me how to put puddings together – it’s only a little twist, but it makes all the difference. Their Small Craft Maintenance Department had asked me to make one for a vessel in for servicing, and they had the last one made at the Poole workshop, which I then used as a model for a few others for the RNLI, including for the Frinton and Walton restored lifeboat, the James Stevens No. 14. So by the time Lucy Lavers needed hers, I’d already done some.”

The pudding, nevertheless, was a fiddly job, ideally needing more than two hands, and Des had help from teenager Tom Curtis, who also seems to have been bitten by the knot bug, and may yet carry the skills forward.

“And I’ve still got that last pudding – they were going to put it in the skip – and it’s now in my museum.”

… and a rope cable from the Sterling Castle, which sank in 1703.

It’s the museum in the Pawsons’ Ipswich back garden, a wooden building with good natural light across the lawn from the workshop, that really articulates the passion, the urge to preserve knowledge accumulated at a time when sail powered the world. It’s probably not the place to take the kids on a wet day, but for those interested enough to make an appointment, there is rope in a wide range of applications – sea chest handles, shaving brush handles, mats, fenders, puddings, and a thick chunk of rope cable from the Sterling Castle, which sank on the Goodwin Sands in 1703.

“That was brought up by divers for English Heritage about four or five years ago. It’s probably from 1699, when she had her last major refit, and it’s heavily tarred hemp, about 3½in in diameter, though there’s no clue to its role.”

The museum, indeed, was a natural progression.

“We’d been visiting maritime museums, often having to make appointments to see things not on public show. The National Maritime Museum at Greenwich, for example, used to have a sail loft as part of its display, but that’s gone. And you can’t find any ropework on public display there, either. We told our contacts worldwide about our museum, not necessarily expecting them to visit, but making the point that we were treating the subject seriously.

“The two parts of the collection I’m particularly pleased with are firstly the rope fenders – things which were mostly thrown away when worn out, but the survivors are a window back into the techniques used around the world.

“The other is rope doormats, made from old rope broken down into single yarns and then plaited into sennit. Again, these are things which were thrown away when worn out, but I’ve found some which have survived in various places around the UK coast, and in other parts of Europe. They were also used on board ship, and as chafing

But these days, Des spends more time researching and writing.

gear.

“It’s the history that has always fascinated me. I’m not interested in inventing a new knot, but I’m very interested in techniques and tools from the past. I’m not a rigger; I wouldn’t design your boat’s rig, but I tend to do the things that riggers don’t know how to do, like making bow puddings, like doing the mats or the decorative ropework.”

In the end, that’s where the passion lies, in preserving the history, which is partly why he spends more time in his study these days, researching and writing, and going out to teach and give talks about the skills and techniques that ran richly through the age of sail and its communities. Among his books is Des Pawson’s Knot Craft, something of a definitive work.

Back in 1982, Des co-founded the International Guild of Knot Tyers, and in 2007, on the guild’s 25th anniversary, he was made an MBE ‘for services to the rope industry’. His uncle really did start something.

Find out more at: despawson.com or email: des@despawson.com