Disquiet on the eastern front – but a sole consolation

As Brexit passes from delivery through dilution to disMay, East Anglia’s fishermen are no longer holding their breath. They’re just trying to get on with making a living. John Worrall reports

Life has got steadily harder for East Anglia’s inshore fleet over the past decade.

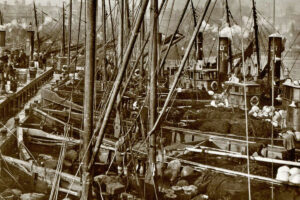

The way things were – drifters at Lowestoft in the early 20th century, at the height of the herring fishery. (Photo: Port of Lowestoft Research Society Collection)

Hit with vastly reduced opportunity on its most valuable fish, bass, almost cleaned out of its next most valuable, sole, zero opportunity on spurdog, and now an impending requirement to fit i-VMS: the most community-sustaining and low-impact part of the industry is fighting to avoid strangulation.

And whether Brexit – if it ever happens, and in what form – improves things remains to be seen.

Not much sole

The last beamer company to work from Lowestoft was Colne Shipping.

Let’s start with a bit of good news, which is that pulse fishing – which has cleaned out the sole – is now being banned, the EU having decided last month to rescind half of the 84 active licences this year, and phase out the remainder by 2021. Pulse research will revert to the original maximum of 5% of any EU member’s beamer fleet, which would limit the Dutch – who have done most of it so far – to a dozen or so licences.

The racks for drying herring drift nets before storage are still there.

This seems finally to be an acknowledgement of the bleeding obvious. Invented in 1992 by Dutchman Piet Jan Verburg, pulsing was soon banned in many parts of the world, including Europe back in 1998 – although that 5% research derogation was allowed in ICES areas 4b and 4c from 2007.

And then, at the end of 2013, came article 14 of the reformed Common Fisheries Policy that said, with reference to the then-imminent landing obligation, that member states could conduct pilot projects to explore ways of avoiding, minimising or eliminating unwanted catches.

Colne Shipping’s boats finished in the 1990s.

This brought an immediate outbreak of pulsing ‘pilot projects’, which threw the supposed 5% maximum over the side. At one stage there were reportedly 112 boats at it, the vast majority Dutch.

In 2015, this North Sea equivalent of the Japanese whaling ‘science’ charade had the ICES working group on electrical fishing, WGELECTRA, saying that the 84 boats licensed at that point – including 35% of the entire Dutch beam trawl fleet over 18m – was a level of effort unjustified on any scientific basis. It said that it was ‘not in the spirit of the previous advice’ and that ‘such a level of expansion is not justified from a scientific perspective’. It was ‘essentially permitting a commercial fishery under the guise of scientific research’.

About 15 inshore boats land to Lowestoft market now…

By 2017, it was adding, “Little is known on the effects of electrical stimulation on the development of eggs and larvae. No studies have been done on the effect of pulse stimulation on the functioning of the benthic ecosystem and nutrient dynamics.”

In itself, this ought to have been reason enough to call a halt right there and then, more particularly since relatively light pulse gear can also work much softer ground than conventional beams, and therefore in areas previously unexploited, that had become stock havens.

… plus the occasional visitor, like the Brixham vivier vessel Ebonnie BM 176, which is nice – and would be even nicer if its landings of whelks were creating jobs by being processed locally, rather than heading straight for Korea.

Non-pulsing inshore fishermen soon knew that it was hammering the sole stock in particular, because their own catches went into steep decline.

Southwold fisherman Paul Klyne, skipper of Laura K LT 974, made the point last month on the BBC’s ‘Sunday Politics East’ programme, saying that his sole catches had ‘plummeted’ in the past five years, from up to 180kg to 30-40kg a day.

“It is just not viable,” he said. “I firmly believe that since the Dutch were licensed to pulse-fish, there has been a major step backwards.”

More ominously, fishermen were reporting dead ground, dead fish and dead everything in the pulsers’ wakes, and that eventually led in January 2018 to MEPs voting by 402 to 232, with 40 abstentions, to ban it – again.

But a lot of boats on this coast are having to turn to whelking for want of other opportunity.

But that didn’t change much except oblige EU commissioner Karmenu Vella to engage in a ‘trilogue’ with MEPs and the Council, and as recently as last autumn, there was little sign of action. The Dutch fishing lobby had been particularly effective in getting that degree of pulsing allowed, despite the 1998 ban, and it still held sway.

It has taken heavy lobbying on the other side of the argument by the France-based NGO BLOOM, together with a coalition of Belgian, French, Dutch, Spanish and UK inshore fishermen, to bring about change.

The UK contingent was spearheaded by Great Yarmouth fisherman Paul Lines, and June Mummery, managing director of BFP Eastern, which runs Lowestoft fishmarket – but the two of them had also lobbied on the home front, having long had the ear of the then fisheries minister George Eustice, through local MP Peter Aldous.

Lowestoft market on a good day for March 2019…

They constantly put forward the reports of ground devastation, and eventually persuaded the minister to fund a CEFAS investigation.

The work was done last year, and is now out for peer review, but findings are rumoured to show collateral damage all the way up the food chain, and at least as bad – and possibly worse – than feared. Either way, DEFRA announced in February that pulse fishing would be banned in UK waters after Brexit, the announcement coming at about the same time as the EU was agreeing its latest wider ban.

… with a lot less sole.

But the CEFAS investigations and their now-rumoured findings were barely in the picture for the EU discussions, which were steered more by a belated acknowledgement of the illegality of the present level of pulsing, in the light of that 1998 ban.

This makes it a rich irony that Brussels is now considering legal action against the Dutch for transgressing the original 5% limit. Did they not know it had been happening? Those plummeting sole catches were probably a clue, but even a cursory look at the Dutch fleet would have helped.

“Ten years ago, we were seeing five tonnes of sole a week on Lowestoft market,” says June Mummery. “Now it’s between 250 and 500kg a week. Dutch pulsers have made millions of pounds by breaking the law. So I want them to reimburse me for what I’ve lost. And fishermen around the southern North Sea want the same.”

Not much bass either

They and local MP Peter Aldous lobbied hard…

Meanwhile, bass catches have also plummeted over the past couple of years, although that is down to regulation rather than stock depletion.

ICES is again involved, but as protagonist rather than observer, advising that the stock remains under pressure, something that flies increasingly in the face of what can be seen on the inshore grounds – which, in turn, reinforces the thinking that ICES is well behind the curve. But again, the scientists can only do as much work as the politicians will pay for.

… and ran a big campaign.

ICES did, in fact, report a slight improvement in bass stock levels last year, and recommended a marginal easing of restrictions. But with the continued limiting of UK bass effort to hook and line, and to netting and trawling by-catch, and only for boats with established track record, and with a closed season in February and March, the small boats are being hurt a lot more than big trawlers that have inadvertently hauled up tonnes of it, and thrown it over the side. With first sale prices at anything between £10 and £15 a kilo, half a dozen decent fish can make the difference between a good and a bad day for an under-10m boat.

But holy soles! The Dynamic Duo, market owner June Mummery and fisherman Paul Lines, had been pushing for the pulse ban, which has finally arrived.

One factor still only tacitly acknowledged by regulators is predation. Back in the autumn, CEFAS held a series of four workshops around the country as part of its Sea Bass Fisheries Conservation UK project, C-Bass, a two-year project funded by the EMFF to promote long-term sustainable bass fisheries in the UK.

The project included a tagging programme, in which bright red cylindrical tags, about an inch long, were inserted into fish to transmit details of location, water depth and temperature. By the time of the presentation in Lowestoft in October, 1,391 tags had been deployed, and results showed that some fish travelled well over 100km, with seasonal movements between the southern North Sea and the Channel, and some evidence of fish returning annually to inshore feeding grounds.

But predation, indicated by a sudden rise to mammalian body temperature, accounted for 20% of those tagged fish, and they were only the ones where the predator actually swallowed the tag.

Bass could be a saviour again…

There’s certainly no shortage of seals.

“Scroby Sands, just off Yarmouth, has 4,000,” says Paul Lines. “And then Horsey, Waxham and Sea Palling, just up the coast, have another 4,000. And there are probably 500 in and around Yarmouth outer harbour.”

He could throw in another thousand or two along the north Norfolk coast, including Blakeney Harbour.

And no spurdog at all

… if it wasn’t for the seals…

As for spurdog, that’s a dead dog for now. “Ten years ago, they banned it,” says June Mummery. “Where’s the science being done on that? People will forget what it’s like. They ban something – they did it with the herring – and now they say, ‘Why don’t people eat herring?’ Because they’ve forgotten what the fish is.”

Her market at Lowestoft is seeing far less fish generally, not only sole and bass, but also cod, which historically was a winter and spring fish on this coast, but seems to have moved north as the seas have warmed.

But plenty of i-VMS…

All this adds further irony to the impending requirement for all inshore boats to have i-VMS.

“Why should we accept that?” says June Mummery. “If they give us fish to catch, we’ll do it. But we’ve got no cod, little sole, and no bass at all at the moment, with the two-month closed season. They spring that upon fishermen who cannot afford to feed their families. Do they want to rub their noses in it? And then logbooks. We’ve got nothing to catch, so why would you want it logged?”

“Most fishermen down this coast have converted to whelk fishing,” says Paul Lines. “It’s the last opportunity. But that’s showing signs of strain. All we can hope for is that in two or three years’ time, with pulsing finished, we’ll have a healthy stock of sole again.”

DEFRA’s i-VMS consultation closed on 14 November, and government responses to points raised were promised within three months. But nothing has appeared.

… and you can’t ban seals.

As matters stand, many east coast fishermen intend to resist it, saying that it will increase operating costs to the point where small, inshore fishing enterprises, also grappling with the landing obligation, will be driven out of business.

According to the consultation documents, airtime costs quoted by three potential i-VMS suppliers range from £114 to £168 per annum at the required three-minute reporting interval. But the bigger imponderable is the cost of repair and, when necessary, replacement of the units, for which individual fishermen will be responsible.

The initial installation will be covered by the EMFF (the MMO will be the applicant), at a cost, according to the consultation, of £1,266 per unit. But a footnote to that figure says: “The costs of units do vary depending on which supplier is chosen and the quantity bought. We received unit cost information from three suppliers, and calculated the average. The unit costs are based on 2018 prices.”

This opens up future costs to huge conjecture, more particularly since there was no indication whether that £1,266 was for one-off installation or bulk-buying for the whole under-12m fleet. And then there is the question of whether approved suppliers with a captive and legally obligated market will be free to charge what they like.

The units use mobile phone technology and, like mobile phones, they wear out or become obsolete. When the three suppliers were asked how long they could be expected to last, only one replied, stating that its device ‘would work for longer than five years, but similar to a mobile phone, become outdated at that point’.

And then there is the question of functionality, and how the technology will cope in the wet conditions of a beach-launched open boat – because boats cannot fish if the i-VMS isn’t transmitting.

Such questions will presumably have been raised in the consultation, along with other concerns, such as data security. The government’s responses will hopefully be illuminating.

Still, you have to keep trying…

But despite these tribulations, this coast still hopes for a Brexit future, now viewed through the lens of REAF – Renaissance of East Anglian Fisheries (Twitter @REAF2018) (Fishing News, 10 January). This is a partnership of fishing industry interests and local councils, spearheaded again by the Mummery/Lines dynamic duo and Peter Aldous MP, who has also been closely involved with the passage of the fisheries bill through parliament. They are always pleased to hear from anyone who is interested in the sector in East Anglia and Essex, and who would like to join the endeavour.

The project recently obtained over £130,000, three-quarters of it from the MMO, to explore opportunities for reinvigoration. The biggest port, Lowestoft, now has about 15 boats landing fish there. At the height of the herring fishery in the early 20th century, there were hundreds. But a feasibility study is underway to assess the current state of play, and to identify what is needed in terms of investment and measures to maximise opportunities. It should be concluded in late summer, and be followed by a strategy for implementation.

“It’s up to government to invest, and get private investors to come here,” says Paul Lines. “But not just British investment. If that fisheries bill manages it properly, fish-processing companies in Holland, France and Denmark should see that it’s beneficial to set up here, and become British entities and invest in our communities.”

And in the end, communities are the key. June Mummery sums it up. “The thing is that it isn’t about the fishermen, it’s about the community. The merchants, the onshore jobs – one job at sea is worth eight on land. The high-skill wind farm jobs aren’t going to save east coast communities, but fishing will. You give me six local boys and I will put them to work, like boys I went to school with, who went fishing and are now well-off.”

Well, it worked once, and if control of the fish off the east coast can be taken back…