Falmouth’s oyster dredging fishery is the only example of a regulated sail-powered fishery in the UK, and possibly in Europe too. Martin Johns reports

Many fishermen often comment that, on a good day, theirs is the best job in the world: stunning sunrises and sunsets, clear blue skies, glassy seas, etc.

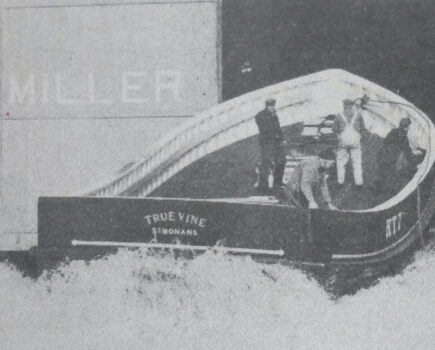

The 151-year-old wooden Boy Willie is skippered by Tim Vinnicombe, Chris Vinnicombe’s cousin. She was bought by the Vinnicombe family from the Strike family of Porthleven in 1923, who themselves bought her from Mevagissey.

However, one element is almost always present to pierce the tranquillity – the noise from an engine.

It’s hard to imagine that in the 21st century a viable fishery exists that relies solely on wind power, and negates the need for the background drone, or indeed the fuel bill, of an engine, spoiling the peace and quiet of a lovely day at sea.

Enter the Fal oyster fishery, a small-scale regulated fishery that is colloquially known as Falmouth oyster dredging. However, the boats involved can also fish for queen scallops and mussels, as well as the native Fal oyster, depending on availability and market demand.

The fishery is currently in its close season, but Fishing News took a trip aboard one of the boats towards the tail-end of the season. Understandably, the number of oysters of an acceptable size caught was lower than it would have been at the beginning of the season. However, this was working out well for the fishermen, as the price currently being paid for oysters was deemed too low, so the main target for the dredgers had been queen scallops, which Chris Vinnicombe explained had really saved their season.

Chris Vinnicombe shoots a dredge overboard at the start of a drift.

Two weeks of relentless late winter gales had eventually moderated to a fresh WSW 4-5, giving a good level of wind for an acceptable speed over the ground, without too much sail area being necessary.

Ironically, the forecast was for the wind to fall further still as the week went on, too light to make wind-powered fishing possible – not a situation that any other fishermen normally find themselves in.

Falmouth’s oyster dredging fishery is the only example of a regulated sail-powered fishery in the UK, and possibly in Europe too.

The dredgers fall into two categories: larger gaff-rigged sail-driven boats up to around 30ft long, and smaller punts that are generally used in the shallower parts of the river and in the creeks, and can be rowed out onto the fishing grounds, where they use a combination of anchors and hand reels to tow their dredges to and fro over a piece of ground. The larger sailing boats have up to three crew, whereas the punts are generally operated single-handed.

The oyster dredging season on the river Fal starts on 1 October every year, and closes on 31 March, although the gathering of mussels is not subject to a seasonal closure. Fishing operations have been regulated by Cornwall IFCA for the past couple of years, taking over responsibility from Cornwall Council. Landings are monitored and catch data is recorded.

Two smaller oyster punts tied up at Mylor harbour.

Dredging is permitted between 9am and 3pm on weekdays, and between 9am and 1pm on Saturdays. No fishing is permitted on Sundays.

The fishing area stretches from a southern boundary between Penarrow Point off Mylor and Carclase Point off St Just in Roseland, extending up into the upper reaches of the Fal to Tresillian, although it excludes Mylor and Restronguet creeks and the main channel into Truro.

The smaller shallower creeks are worked by smaller punts using the anchor and reel system to tow their dredges. Some operators have both punts and sail-powered boats to ensure they can work in all areas. The boats tow their dredges over the shallow parts of the Fal, avoiding the very deep channel that winds its way up through the estuary and affords deep-water lay-up anchorage to big ships of up to 195m in length on moorings near the King Harry Ferry.

The painstaking process of sorting the catch begins after a short tow.

The sail-driven dredgers, ranging from around 6m in length up to around 9m, are gaff-rigged, carrying a large mainsail aft of the mast, a stay-sail forward of the mast, and a jib-sail forward, secured at its lower forward corner to a bow-sprite extending some 2m ahead of the stem post. The biggest of the sail-driven dredgers work up to four dredges.

Rachael Anne is a GRP-hulled ‘Heard 28’, built just a mile or so from its Mylor base by renowned yacht builder Martin Heard at Tregatreath Boatyard in nearby Mylor Bridge. Initially built as a top-class sailing yacht for a local St Mawes consortium of owners, it was converted some years ago for commercial shellfish dredging by its current owner Chris Vinnicombe, who also owns two larger Mylor-based steel scallopers, Lily Grace FH 444 and Debbie V FH 555.

Although no engine power is allowed during fishing operations, it is permitted to get the boat to and from the fishing grounds, and is obviously available to use in the event of an emergency. Rachael Anne’s engine is a Yanmar 3GM model, and is installed entirely below the deck of this deep-drafted craft.

The boat is skippered by Chris Vinnicombe, with his son George as crewman. Three dredges are worked from wide side-decks, or ‘waterways’, to use the correct sailing parlance. The dredges can be worked from either the port or the starboard side, depending on wind and tide conditions.

A full bucket of queens is bagged up.

The dredges are made of round steel bar, and are 12mm diameter, with a width of approximately 600mm, although dredges up to 1,200mm wide are permitted. A flat stainless steel blade scrapes the shellfish from the seabed. Behind this, a light chain-link belly with a netting back is terminated with a hardwood batten. Dredges must not exceed 20kg in weight.

Each dredge is shot over the side of the boat, attached to a rope warp which is moused off at the appropriate length to a twine weak link attached to the gunwale. The inner end of the main warp isn’t made fast to the boat, but is instead attached to a buoy that can quickly be thrown over the side if a dredge should come fast on the seabed, as a sail-powered boat cannot be quickly stopped like a powered boat could be. The floating buoy ensures that the lost dredge can be retrieved later, once the boat can be safely turned upwind.

Being sail-powered, the boat’s course over the fishing ground is governed by a combination of wind and tide. On the day Fishing News visited, a moderate southwesterly wind of around force 4 was blowing, combined with an incoming tide all day. Luckily, the direction of the drift meant that the dredgers were able to easily avoid the 16,000t Russian cargo ship Kuzma Minin, which had been moored in the Carrick Roads since being recovered off Gyllyngvase beach near Falmouth after running aground in December 2018.

Large scallops are sometimes caught, as well as oysters and queens.

After a short steam from the mooring just off Mylor quay out into the river, the Yanmar engine was cut and Chris Vinnicombe carefully unfurled and set the sails to suit the conditions, reefing in the mainsail to ensure the speed over the ground was slow enough to keep the dredges at the correct angle of attack on the seabed. Constant adjustment to the sails was necessary throughout the day to keep a constant towing speed as the wind speed and tidal flow changed.

Around 12 sailing boats and seven or eight punts take part in the fishery.

On the day in question, there were 10 sailing boats working the shellfish beds in the Carrick Roads area of the Fal, sailing upwind to the southern boundary of the river Fal fishing area between Penarrow Point and Carclase Point, before turning and shooting their dredges at the start of a drift upriver.

The dredges are towed for roughly as long as it takes to sort the contents of the hopper from the previous tow. Once hand-hauled, the dredge contents are tipped into the hopper, and the dredge is immediately shot again. This cycle is repeated several times during a drift, before the dredges are hand-hauled, the sails reset, and the boat sailed upwind again to start another drift. The minimum landing size for oysters is 67mm, and if mussels are targeted, they must exceed 50mm in length.

Once sorted, queen scallops and oysters are temporarily stored in buckets located below the sorting tables, before being transferred into bags when the bucket becomes full.

Chris Vinnicombe enjoys a well-earned sandwich as he sails Rachael Anne back upwind to start another drift.

Overall, the catch for the day comprised 17 bags of queens and three bags of oysters.

Once back in Mylor harbour, Chris Vinnicombe suspended the bags of queens in deep water, to enable them to clean themselves of sand and silt, ready for collection by the merchant the next day, while the oysters were taken to one of Chris’ own ‘lays’ further upstream in Mylor creek, where they were carefully relaid at high water, to be allowed to grow further and be reharvested later in the year, when demand, and consequently the price paid for them, would be much higher.

As this was the final week of the permitted season, and the wind was due to be too light to make sail-powered fishing possible for the rest of the week, Rachael Anne had caught its last oyster for the 2018/19 season. The boat was due to be moved to a drying mooring on the edge of the harbour the next day, to allow well-earned maintenance and a paint-up to take place over the course of the summer, before the fishery kicks off again in earnest at the beginning of the new season at the start of October – a time that is celebrated in Falmouth with the much-vaunted Fal Oyster Festival.

This features four days of cookery demonstrations by celebrity chefs, live music, craft demonstrations and stalls, as well as a working boat race, a grand oyster parade and an oyster shucking competition.