Veteran Filey fisherman Colin Jenkinson reflects on his 72-year career – and centuries of Jenkinson fishing heritage. John Worrall reports

Colin Jenkinson has retired. After nearly 72 years of fishing for a living and just turning 85, another member of the Filey – and, by extension, Scarborough – Jenkinson fishing clan has called it a day and sold his last boat, which was a Kingfisher 24.

“Yup, I’ve retired now. We’re going up to the MMO on Thursday to swap the paperwork over to the new owner.”

All is shipshape.

There’s an air of wry satisfaction about him when he says that, as though thinking of all the work and the fear and the fun over that many years, and having come out the other side, and being able to retire in the warmth of all the things he did.

Because he has done what scores – more likely hundreds – of Jenkinsons have done over the past couple of centuries: make a living from the sea. Several other big fishing clans have worked – still work – from that part of the Yorkshire coast, but dig into the fishing history of Scarborough and, more particularly, Filey, and Jenkinsons come up more than most. The family tree goes all the way back to William Jenkinson, who died in 1762.

But not all of them served a full term. St Oswald’s churchyard in Filey has many headstones for Jenkinsons taken by the sea, and they are only the ones who were found. In the age of sail, winter gales from the northeast quarter put many a fishing boat – and collier and barquentine – onto a lee shore. And even in the days of steam, things weren’t always shipshape, as evidenced by the case of the drifter Research – a ‘poor affair, worn out’ – which sank in 1925 off Flamborough Head with the loss of all nine crew, five of them Jenkinsons.

Colin may have left the sea, but he still has a wheelhouse, complete with wheel and sea dogs.

Colin started in the summer of 1948 in his school holidays.

“I went as fourth hand in the coble Rosemary, owned by Castle Mainprize, lining and potting from Scarborough. He put me on a quarter share, and my best week was £15, which was a lot back then, when some Scarborough fishermen were going labouring for the council at a fiver a week because the fishing was poor.”

He started full-time on the Rosemary when he left school in 1950.

“My dad, Charlie, was on her too, and he’d said that I weren’t going fishing; he wanted me to get a trade. But I said I were, and I did. And I’ve no regrets. During my first winter, fish was still on controlled price after the war, with cod fetching about six bob a stone and haddock four shillings and sixpence. But the next winter, it came off control, and we were getting a quid a stone for cod, which was a fortune. The lads who’d been labouring were straight back to fishing.”

In 1963, Colin and Rachel bought their first boat, the Reekie-built Courage SH 106, which they renamed Margaret and William SH 142.

He worked on the Rosemary until 1953 or 1954, and then Castle Mainprize – he of another big local fishing clan – bought a keel boat from Tarbert.

“He brought her through the Forth and Clyde canal, and renamed her Marian after one of his daughters, and I worked on her for a while.

“Then I went to a 50ft keel boat called the F and S Colling, a potter/trawler, although she was mostly trawling. She was built in ’56, and so it would have been ’57 and ’58 I was in her.

“Then, in 1960, I went into the Margaret Jane, owned by Thomas Jenkinson Mainprize, known as Denk, and I married his daughter, Rachel, that year, on her birthday – diamond wedding coming up this year. I worked for her dad for two or three years, trawling and occasionally on the herring, but there was a dispute within Rachel’s family and so, in 1963, we bought our own boat, our first, which was the Courage SH 106.”

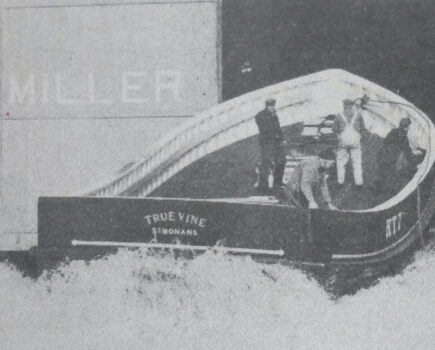

Courage was a wooden boat built by Walter Reekie, who had yards at Anstruther and St Monans.

Built at Macduff in 1984, the 60ft whitefish side trawler Our Pride was shelterdecked on the port side while the starboard side was left open for working the single-rig hopper trawls. (Photos: David Linkie)

“We renamed her Margaret and William after our two children, and renumbered her SH 142. She cost £1,200, of which Rachel’s Aunt Alice lent us £500, and we worked her from ’63 to ’67, when we sold her and built a steel trawler, Our Margaret SH 137, at Knottingley.”

Their fishing pattern had been lining in winter, with Rachel skeining and baiting the lines with mussels, and a combination of trawling and potting in summer, when Rachel would run a crab stall, selling to visitors. But after they got Our Margaret in the 1960s, it was mostly trawling, and they did very well.

“It was a boom time for trawling at Scarborough, Whitby and Brid. That real hard winter of ’62/63 started it. There were plenty of cod for a long time after that, perhaps because the water was colder. There was good fish down by Mablethorpe inshore, and we did well there.

In 1967, the Jenkinsons built the steel trawler Our Margaret SH 137. (Photo: David Linkie)

“And then we sold her and built Our Rachel SH 97, in 1972. And we kept her for quite a while, because we then built one called Our Heritage SH 237, in 1976 – another trawler – and we worked them together, with our son Bill, who’d been fishing since he left school, taking Heritage. They were 55/56-footers. All our boat registration numbers had a seven in them, except for Margaret and William which was SH 142 – but that’s two times seven, making 14.

“And then we built the Our Pride SH 77, a 60-footer, at Macduff in 1984, again a trawler. We’d have up to six crew on her, landing to Scarborough or Grimsby. Around ’86 or ’87, we started fishing on the gas and oil pipelines, towing with the pipe right between the two doors, so that you were right on top of it. The pipes were very good for cod, perhaps because there was always food around them – sand eels particularly.”

“After that, Bill wanted to go potting. So we bought a 33ft fast boat called Shannon SH 268. After her, two years later, we built another U10, Our Sharon SH 7, and then also had Pisces FD 512, which was a scalloper, and Bill took that – but he then became ill. He died of cancer two and a half years ago. But his son – our grandson – Will is fishing with Our Sharon, although when he was a boy, he always wanted his granddad to keep Our Pride until he was 17 or 18, so he could take her.”

Our Pride SH 77, seen here in 2001 with three generations of Jenkinsons – Will, Bill and Colin – did well at trawling in the late 1980s.

In between all this, for a few years after the turn of the century, Colin left fishing and had a 46ft passenger boat, the Endeavour, which he worked from Whitby. But then he went back to fishing with an U10 trawler, Marie Kelly OB 2, which he bought from Ireland. He worked her for a couple of years before selling her in 2012 and buying Ennis Lady PZ 50 – the Kingfisher 24 that he’s just sold.

“So I’ve done the full circle in types of fishing, and come back to potting to finish up with.”

But then, in amongst all that, he did 13 years as lifeboat crew, starting in 1954.

There had been a disaster on 8 December when the lifeboat ECJR turned over in a storm. It had just completed one call-out and the crew, having already been out in their fishing boats since the early hours, were having a cup of tea in a cafe. But then a storm blew in, and six fishing boats, none with radios, were reported overdue. The lifeboat found three and escorted them home, and after five hours was lying to off the Castle Hill when she received a radio message from Whitby that the others – Courage, Pilot Me and Rosemary, on which Colin was working – had got in there.

Colin’s grandson Will is now working with the fast potter Our Sharon. (Photo: David Linkie)

As the ECJR turned into Scarborough harbour, she was hit by two big waves and capsized, and although she was self-righting, five men were thrown into the water, and three of them drowned. Colin signed up as crew straight away.

And then there was the time, when fishing, that they just missed out on salvage, after the 394t Fleetwood trawler Navena started to take water 12 miles off Scarborough, and the crew launched liferafts, but left her under power.

“Everybody had got off her, but she was heading straight for Filey Brigg.”

Three fishing boats, including Colin in Our Heritage, tried to turn her.

“One of the boats had picked up a liferaft, and we thought about using that as a fender to push her round. But then we managed to get one of our crew aboard, and he got into the wheelhouse. But there must have been an emergency stop of some sort, because the engine stopped.

The potter Ennis Lady was Colin’s last boat. (Photo: David Linkie)

“So we got a rope aboard and started to tow her towards Whitby. But she was rolling about and taking more water, and getting sloppier and sloppier, and so we made for Scarborough. But the harbour master wouldn’t let us in, thinking she’d sink and block it – and all the time, there was a bloke from the insurance company threatening us with all sorts. We were going to try to tie her to the end of the pier, and if we had got her there, she was ours. But she got a bit too far over, and then lay right on her beam end, and we had to beach her just south of the harbour. And then she dug into the sand, and finished up staying there for four months. Put Scarborough on the map, she did.”

And then there was the suspicious package.

“One day in Our Pride, we trawled up a parcel, but we wanted to keep fishing, and so we stowed it and re-shot.

“When we got in, we landed it at the end of the pier and asked the watchkeeper to ring the drug squad, and when they came round, it turned out to be cannabis which had been thrown over by a boat being followed by the police. And they said: ‘What are you turning this in for? You should have turned it into cash.’”

Now that Colin is out of fishing, what changes has he seen in his time, and how does he see the future for those still fishing – particularly the younger lads?

“Things have changed completely. The lads who were in cobles at Filey have now got bigger boats and work out of Scarborough – maybe eight or 10 of them, along with perhaps eight or 10 Scarborough boats as well. It’s been about that number for a few years now, and most of them are potting, because shellfish look okay. But there aren’t any finfish. Some who’ve tried trawling the last couple of years have got nothing. There’s no cod. I think the last really good year for whitefish around here was about 1999.”

This means that Scarborough harbour in winter is nowhere near as busy as it was. Back in the first half of the 20th century, when boats still followed the herring down the North Sea in the autumn, you could walk across the harbour from one boat to the next, as you could in most herring ports.

“It was a hive of industry down there. But now, it’s like a ghost town in winter. But I think there’s still a decent living to be made with shellfish. There’s also still a little bit of salmoning, but that’s only two months a year now – although they did really well while they were at it this year.”

So for now, the various fishing families in Filey and Scarborough continue the business, as interwoven as ever – though that interweaving has produced a few complications in the area’s fishing history, with the limited number of surnames, and then of Christian names.

According to the Scarborough Maritime Heritage Centre website, back in 1900 there were 10 John Jenkinsons, eight Matthews, six Williams, six Thomases, six Georges, five Richards and four Roberts. At virtually any time after about 1850, there were at least six John Jenkinsons of fishing age.

So families tried to simplify matters by adding the mother’s maiden name to a child’s Christian names as a distinguishing feature, and that started early among the Jenkinsons, with Edmond (baptised in 1811) and Castle (baptised in 1824). But Castle figures mostly in the Mainprize family – as in Castle Mainprize, with whom Colin first went fishing – which happens to be the clan of Colin’s wife Rachel.

And by Rachel’s time, things had compounded, because she already had Jenkinson as her second Christian name – she was Rachel Jenkinson Mainprize – and so, when she married Colin, she became Rachel Jenkinson Jenkinson, which sounds double-barrelled but isn’t, and still causes fun and games with officialdom when filling in forms.

But then, what about Colin? He stands out among all the Johns, Matthews, Williams, Thomases, etc – so how did Colin come about?

“Well, I was born in the old Scarborough hospital, but my mum had to stay in there, and her sister came down from Newcastle – she were a Geordie – to take me to be christened, and she named me after one of her ex-boyfriends.” Which certainly simplified things – if nothing else.

But now, Colin and Rachel can throttle back and cruise towards their diamond wedding celebrations, and get on with the next phase – Rachel continuing to take her six golden retrievers to shows, Colin reflecting on a job well done, and keeping an eye on the fishing from their timber-panelled front room, which is decked out like a spacious wheelhouse, complete with wheel.

You can get a flavour of what it has all meant to them on the Scarborough Maritime Heritage Centre website: bit.ly/30o43uN which has a five-minute Listening Project conversation between Colin and his grandson Will.

It sounds like a life well lived.