With a number of Scottish boats joining the blue whiting fishery off the west of Ireland this month, David Linkie looks back to a trip in 2012 on the former Lunar Bow PD 265

The possibility of documenting a blue whiting trip was initially raised in the first week of 2012, and while the best-laid such plans often go awry, on this occasion everything fell into place.

Lunar Bow passing St Kilda, 20 hours after leaving Peterhead. (Photo: Andrew Ritchie)

The Fraserburgh-based Challenge landing blue whiting to Denholm Seafoods Ltd at Peterhead.

The Type 42 destroyer HMS York, encountered on a live gunnery exercise off Cape Wrath.

Pathway steaming in company with Lunar Bow.

Standing by to shoot.

Checking that the net is shot cleanly.

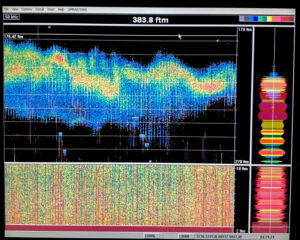

Good marks of blue whiting in the dark, displayed on a Simrad ES-60 sounder. (Photo: William Buchan)

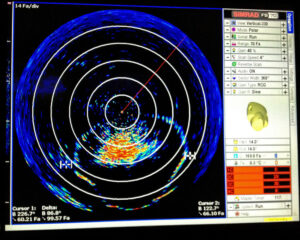

Straight down the middle – Lunar Bow’s Simrad FS-70 trawl sonar displays a good flow of blue whiting entering a well-shaped net. (Photo: William Buchan)

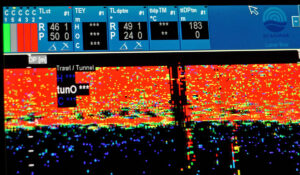

Blue whiting as shown by the Scanmar Scanbas tunnel sensor.

Hauling underway.

Guiding the trawl sonar pocket aboard.

Hauling the blue whiting trawl onto the drum.

Lunar Bow’s stern lights illuminate a 460t haul of blue whiting.

Taking the tail end forward.

Using the mid-line winch to dry up the bag.

ecuring the sock to the Karm fish pump.

Pumping underway.

Blue whiting flow into Lunar Bow’s forward RSW tanks.

Job satisfaction – David McLean, David Ritchie and mate Mark Buchan monitor the flow of fish from the C-Flow separator.

The reinforcing beckets are essential to prevent the bag from blowing.

As I was preparing to head to Glasgow for Fishing 2012 towards the end of March, the forecasts for the week ahead, which showed a developing large area of high pressure, suggested that it would be wise to put a sleeping bag and the necessary safety equipment into the car in addition to a suit.

This thinking was confirmed during a brief chat with skipper Alex Wiseman, chairman of the Scottish Pelagic Fishermen’s Association, within an hour of the exhibition opening, and another the following morning with Peterhead skipper Georgie Buchan.

A couple of text messages early on the Saturday afternoon resulted in a foggy drive across Scotland to Peterhead, rather than a return to North East England. The initial plan was to go aboard Kings Cross 30 hours later, but with some blue whiting still to land, the decision was made for Kings Cross to delay sailing, to avoid the possibility of three boats waiting to land to Lunar Ltd later in the week. My gear was therefore put aboard Lunar Bow, following skipper Alex Buchan’s much-appreciated offer of a trip.

Having fished blue whiting in the preceding two weeks before landing shots in the region of 550t, Alex Buchan was looking for a slightly smaller catch to complete Lunar Bow’s quota for 2012.

Usually targeted in February and March, from the Porcupine Bank 200 miles off the west coast of Ireland and northwards along the edge of the deepwater towards St Kilda, down to 450 fathoms, the blue whiting fishery has long been recognised as being potentially the most difficult pelagic fishery to work.

In the years running up to 2012, skippers and processors in North East Scotland, Ireland and Norway had worked diligently to develop new markets for blue whiting, with catches being processed for human consumption rather than fishmeal. At a time when the annual TAC had been drastically reduced, following unregulated fishing due to a previous lack of international fisheries management agreement, this highly significant development was enabling greater financial benefit to be realised from minimal impact on stock levels.

Although a number of Norwegian vessels had started to fish blue whiting west of the Porcupine Bank in both EU and international waters in the second week of February, Scottish skippers had waited five to six weeks until the fish had moved considerably closer to the Outer Hebrides, in order to reduce steaming time and ensure that their catches were landed in optimum condition for processing. Today, with bigger boats, most participating Scottish vessels tend to operate from Killybegs, thereby starting the season earlier and fishing west of the Porcupine Bank.

Lunar Bow departed Peterhead shortly before midnight. Passing the Norwegian midwater trawler Haugagut H-50-AV landing blue whiting to Fresh Catch on leaving Peterhead harbour, Challenge FR 226 flushing her RSW tanks while waiting for the tide into Fraserburgh harbour, and a returning Chris Andra FR 227 midway across the Moray Firth provided a reminder of the international dimensions of this fishery.

Further evidence of this had been provided in preceding weeks, when shots of blue whiting from a succession of Norwegian midwater vessels had been bought on the Norges Sildesalgslag electronic auction by companies in Killybegs and Norway, as well as by Shetland Catch and Fresh Catch at Lerwick and Peterhead respectively.

With Pathway PD 165 keeping station on the starboard side of Lunar Bow, the two Peterhead vessels rounded Duncansby Head into the Pentland Firth before dawn the following morning. A tranquil steam west along the top of Scotland on an exceptionally quiet morning was interrupted by a message on Channels 16 and 74 from HMS York, a Type 42 destroyer, stating: “Warship York is engaging in live gunnery fire within the artillery range 10 miles northeast of Cape Wrath. Please pass to the north of our position.”

The two crewmen on watch, Mark Buchan and David Ritchie, immediately made the required course alteration, which was paralleled by Pathway. Although it entailed a dog-leg of some 15 miles, the detour was reduced by skipper Alex Buchan’s decision to head out across the Minch, rather than steam south through it, as boats on passage to the blue whiting grounds had done in previous weeks, before leaving Barra lighthouse to starboard.

This reflected the fact that since they had started to fish blue whiting 80 miles due west of Killybegs two weeks earlier, the fish had moved steadily northwards, following the contours of the continental shelf, at the rate of 10 to 15 miles per day. As a result, Lunar Bow and Pathway were preparing to start searching in the vicinity of 57.5°N and 9.6°W, nearly 24 hours’ steaming time and some 300 miles from Peterhead.

Shortly after we had enjoyed a bowl of Gordon Pirie’s homemade and very tasty mushroom soup, Lunar Bow passed the Butt of Lewis before heading southwest towards St Kilda, the most important seabird breeding colony in Europe. The near-sheer sea cliffs of Stac An Armin and Stac Lee, at 191m and 165m the highest sea stacks in Britain, together with the islands of Boreray, Soay, Dun and finally Hirta – where the St Kildans lived, mainly near Village Bay, until being evacuated in 1930 – slipped past two miles off Lunar Bow’s port side as day turned into evening, and the crew were served a fine supper of Chicken à la King.

With Lunar Bow and Pathway scheduled to begin searching shortly before midnight, when the boats would be some 40 miles southwest of St Kilda, most of the crew took the opportunity for three hours in their beds – leaving plenty of room in the dayroom for the keener football fans onboard to watch a live Sky match.

Within 30 minutes of skipper Alex Buchan reducing the propeller pitch and starting to search for marks, with the Simrad ES-60 sounders showing 460 fathoms of water under Lunar Bow’s keel, the call of ‘away to shoot’ resulted in deck gear being swiftly donned.

On the vessel’s two previous blue whiting trips, better catches had generally been taken in daylight, but with a wide distribution of light hazy marks appearing on the Kaijo sonar and the Simrad sounders, the crew prepared to shoot the midwater trawl, in the expectation of making a fairly long tow, before hauling in time to begin searching again shortly before dawn.

After tracking the selected marks to verify their direction for 20 minutes, the pennants holding the sock and the first section of the brailler – which had already been outhauled in preparation for shooting – were released from the boat deck. The characteristic becket-reinforced brailler then started to disappear into the darkness beyond Lunar Bow’s stern lights.

Lunar Bow was fishing a 2,048m blue whiting net constructed from nylon by Egersund Trål. The first sections of the long winged trawl incorporated 32m meshes, which were gradually reduced down to 16m towards the belly sections. The centre quarter of the bosom was rigged with a chain footrope, flanked on either side by leaded ropes.

Nine years on, the new 80m Lunar Bow, delivered by Karstensens in January 2020, tows a custom-designed 2,048m blue whiting trawl utilising Jacinto twine in the wings, which performed consistently well on the previous boat, together with blue whiting bags from Egersund Trål.

With shooting away proceeding smoothly – including positioning the Simrad FS-70 trawl sonar transducer securely in the headline pocket – the crew prepared to clip on the double toe-end weights (2 x 1.1t) as the last sections of the net came off the drum, followed by 260m of 38mm-diameter nylon-covered Dyneema sweeps.

After connecting the sweeps to the Thyborøn Type 10 double-foil trawl doors (15m2/3,700kg) and retrieving the pennants, engineer Alan Lawson started to release 1,200 fathoms of 38mm trawl wire from the wheelhouse fishing console, as Lunar Bow started to tow the gear at 3.6-4 knots, with 68-70% pitch on the Wärtsilä 3,800mm-diameter propeller.

As fouled meshes resulting in partial gear opening is a constant risk when shooting away large blue whiting trawls, a clear display from the trawl sonar of the net opening symmetrically, before reaching a typical opening of 105 fathoms by 75 fathoms, was well received in the wheelhouse. So too was the appearance, 15 minutes later, of the first signs of fish at the mouth of the net, subsequently followed by activity from the tunnel sensor – part of Lunar Bow’s Scanmar Scanbas trawl-monitoring system.

Although the tops of the marks were initially standing at 220 fathoms, the yellow and pink colours indicating greater concentrations of fish were down between 260-270 fathoms, where the gear was lying.

After towing south for 20 minutes, the first Marport catch sensor was triggered. However, this positive sign was offset by a blank sonar screen, which was also reported by skipper Georgie Buchan on Pathway, which was towing on a parallel heading two miles to port.

Fifteen minutes later, Lunar Bow’s sonar again started to display echoes ahead to starboard. Following an appropriate course alteration and 20 minutes of inactivity at the mouth of the net, larger quantities of fish began to appear between the wings as the water depth reduced to less than 400 fathoms, with the main concentration of blue whiting now lying at around 220 fathoms.

When the fourth egg activated shortly before 3am, indicating somewhere in the region of 400t of blue whiting, the decision was taken to haul. Twenty minutes later, the doors were secured as the sweeps started to be taken onto the drum. Difficulties in hauling a bag of blue whiting are relatively common, but all went smoothly this time, apart from the sweeps dipping almost vertically shortly after being unclipped from the doors – a situation that was immediately addressed by a thrust ahead and quickly hauling the slack onto the drum.

Ten minutes later – during which time the 635m polypropylene 9in-diameter lifeline, which included a 30m 10in-diameter section at the bag end, was connected to the Karmøy 50t lifeline winch on being released from the starboard toe-end weights – a well-filled bag began to emerge into Lunar Bow’s stern lights. The tail end of the brailler was then quickly hauled forward by the aft purse winch, located immediately forward of the accommodation casing, at the same time as the 34t midline winch was used to dry up the bag.

After taking the sock aboard and clamping it in position over the inlet, the 24in Karm fish pump, together with the fish and hydraulic oil pipes, was lowered into the water forward of the forecastle deck by the main deck crane.

With the brailler floating well alongside Lunar Bow’s starboard side, while continually being dried up by the midline winch in ideal conditions, blue whiting flowed continuously into the C-Flow separator amidships during the next 75 minutes, from where they were evenly distributed into seven RSW tanks forward and aft in an equal amount of pre-chilled seawater to ensure optimum levels of catch quality.

As with earlier catches from what is a 100% clean fishery, the blue whiting being pumped aboard Lunar Bow displayed uniform physical characteristics, around 300mm in length and with a weight of 180-200g.

A textbook operation ended just before 5am, when after taking the fish pump back aboard and releasing the sock, the brailler was hauled back onto the drum. Skipper Alex Buchan then set the first waypoint for the 300-mile return steam to Peterhead, with Lunar Bow having caught all of her remaining quota.

After taking 150t in the dark from a haul restricted by a fouled wing, Pathway took 350t from an early-daylight tow in a similar area, when fishing alongside the Fraserburgh-based Taits FR 227.

Having left Peterhead at 9pm the previous night, an outward-bound Kings Cross steamed past Lunar Bow on a reciprocal course early that afternoon just north of the Butt of Lewis. With their annual blue whiting quota now taken, Lunar Bow’s crew donned their deck gear again after dinner to clean and shoot out the bag before hauling it back onto the drum, ready to be taken ashore and stored away for next year.

After passing the 75m Norwegian pelagic vessel Brennholm H-1-BN at Cape Wrath heading west to conduct a blue whiting survey, Lunar Bow had a clear steam along the top of Scotland to enter the North Sea shortly before 11pm. Four and a half hours later, with the ropes secured at the end of a 52-hour trip, the first blue whiting were being pumped ashore at Peterhead for weighing, packing and freezing in 20kg cartons ahead of export to a number of international locations, probably including Africa, China and Russia.

Later that day, Pathway berthed in Fraserburgh to land 550t of blue whiting, while Taits docked at Peterhead later that night to land a similar shot to Denholm Seafoods. With Lunar Bow completing landing early on the Thursday morning, Kings Cross arrived at lunchtime to land the UK’s remaining 2012 allocation of blue whiting.

With a much larger share of the TAC, Norwegian vessels continued to catch blue whiting well into April 2012, by which time the fish were being caught up to 100 miles northeast of St Kilda, and some 500 miles from where the first catches had been taken two months earlier.

Thanks again, lads, for making this fishing feature possible – and for your friendship.

Challenging blue whiting fishery

Blue whiting Micromesistius poutassou is widely recognised as being – by some margin – the most challenging fishery engaged in by Scottish pelagic vessels.

In addition to the difficulties inherent in fishing in the North East Atlantic along the edge of the deepwater, one of the key challenges faced by skippers and crews on a regular basis can be attributed to the rapid decompression of fish brought to the surface from 250-400 fathoms.

The rapid expansion of air from such a sizeable concentration of fish can cause the bag to surface with considerable violence. The impetus generated during hauling, however slowly it is controlled, frequently results in the bag almost clearing the water, particularly the tail end, which can be subject to a lash effect.

In a worst-case scenario, when the bag blows to the surface before the trawl doors are even up, the uncontrollable strain on the gear can be such that the trawl wires break away, with the result that a complete set of gear is lost.

In order to avoid this eventuality, and to facilitate all-round safer handling of the gear, the normal working practice is for the last few hundred fathoms of wire to be hauled dead slow, with the boat idling in the water for 10 minutes. Securing the doors and transferring the long sweeps onto the net drum allows a crew to have greater feel and control of the situation, although even then, narrow margins prevail.

The rapid decompression of the fish and the resulting momentum generated by the increased buoyancy frequently leads to the boat being towed astern. This situation is usually handled by reducing the pressure to the net drum, thereby allowing the sweeps to feed out when the strain on them reaches a critical point – in much the same way as an experienced angler plays a freshly hooked salmon.

To restrict the meshes from opening too far, which would result in the bag blowing, blue whiting braillers are rigged with nylon retaining beckets spaced at 1.5m along their full length. This maximises the strength afforded by generally using an inner bag of 50mm in addition to a heavy 80mm mesh outer cover, which itself is doubled on the bottom of the net where the strain is at its maximum.

Another major difficulty can occur when, in taking a haul of some 300t of blue whiting which are nearly ready to spawn, the bellies break due to the rapid decompression, with the result that the bag drops like a stone to put severe strain on the gear. Even after the fish have spawned, blue whiting need to be pumped aboard as quickly as possible, to minimise the risk of fish still in the bag losing air and therefore buoyancy.

New marketing structure adds value to traditional fishery

In the years running up to 2012, the combined endeavours of processors and skippers had resulted in the blue whiting fishery undergoing dramatic changes, with far-reaching value-added benefits for all concerned.

In 2012, six midwater vessels from North East Scotland, together with the Kilkeel-owned Voyager, which operated out of Killybegs, fished the UK’s blue whiting allocation of 12,563t, all of which was landed and processed for human consumption.

This marked a complete reversal of the fishing pattern that had prevailed for more than 35 years, since Scottish pelagic vessels started to fish blue whiting for fishmeal outlets in the mid-1970s along the edge of the deepwater west of St Kilda.

With Norwegian vessels beginning to develop a large-scale fishery in the early 1970s, the first exploratory blue whiting trips by Scottish boats were undertaken between 1974 and 1976. Engaged by the White Fish Authority and the Highlands and Islands Development Board, the Peterhead pair-trawlers Shemara PD 78 and Fairweather V PD 157, together with the Ayrshire purser Pathfinder BA 188, fished successfully to the west of Barra.

This favourable outcome resulted in a number of other Scottish midwater vessels fishing blue whiting commercially in the late 1970s. Lacking the power for single boating and operating near the limits of their capability, including in some cases having to use two barrels of wire each for the headline and footrope warps, boats like Pathway PD 65, Lunar Bow PD 118 and Vigilant PD 165, together with the newly built next-generation purser/trawlers Andra Tait FR 226, Taits FR 229 and Chris Andra FR 221, pair-trawled for blue whiting. Catches were either landed into the fishmeal plants at Stornoway or Ardveenish in Barra, or into Mallaig or Ullapool to be sold for pet food. However, high expenses coupled with low prices yielded marginal profitability.

Following successful larger-scale seasonal blue whiting activity by the Humber-based freezer stern trawler St Benedict H 164 and the pursers St Loman H 487 and Grimsby Lady GY 430, more Scottish boats, including Quantus, Azalea and Kings Cross, joined the fishery. With continuing investment in larger vessels, the significance of the blue whiting fishery from a UK perspective increased towards the end of the 1980s, when Orcades Viking II K 175, Sunbeam FR 478, Christina S FR 224, Omega B FD 221, Ocean Way PD 465 and Altaire LK 429 were among the vessels taking part.

With an increasingly modern fleet more on a par with that of Norway, Scottish involvement in the blue whiting fishery reached new levels towards the end of the 1990s, though landings were still exclusively for fishmeal.

Being a ‘straddling stock’ in the North East Atlantic, blue whiting was found in the EEZs of the EU, Faroe, Iceland and Norway as well as international waters. This meant that international co-operation was essential for effective regulation. However, until 2006, the first year of coastal states’ agreement on management and shares, this was conspicuous by its absence.

During the early 2000s, Iceland, Faroe and Norway fished blue whiting without setting a TAC, while the EU set its quota share based on its historic catch percentage applied to the scientific advice. The actual catch therefore far exceeded the TAC recommended by ICES.

In 2003, catches of blue whiting reached a record high of 2.3m tonnes, making the fishery the biggest one in the Atlantic – whereas the advice from ICES was not to exceed 600,000t.

After the coastal states reached agreement in December 2005 to end the period of what was sometimes referred to as ‘Olympic’ fishing, the blue whiting fishery was regulated under this agreement. It gave the greatest share to the EU, although Norway held the largest annual quotas through quota swaps.

There was considerable irony in the fact that at a time when catchers and processors were striving to change the whole thrust of the fishery towards new markets for human consumption, thereby adding significant catch value, TACs started to be drastically reduced.

However, in providing an alternative seasonal fishery after the early-year western mackerel and Atlanto-Scandian activity, the blue whiting fishery continues to provide Scottish skippers, crews, processors and port operators with an opportunity to extend their business platform for a short but significant period between February and the start of the North Sea herring fishery in mid-summer, while supplying a top-quality source of protein to grateful recipients.