In this occasional series, David Linkie looks back on fishing trips, some of them in fisheries now sadly consigned to history, that he has experienced over the past 30-plus years

For generations of inshore fishermen, launching and hauling out boats from sand and shingle beaches was part of their well-established daily routine. Although hazardous and strenuous, the lack of natural harbours in their immediate neighbourhood left local fishermen with little or no other option than to accept the difficulties and constraints of beach launching.

Gentle Barbara is launched by tractor…

From the Humber north to the Scottish border, traditional Northumberland and Yorkshire cobles were worked from the shore at a number of locations, including Craster, Boulmer, Newbiggin, Redcar, Filey, Flamborough Head and Hornsea. While capstans were used at locations where steeper gradients prevailed, often in conjunction with log rollers, tractors and bogies were generally the preferred option.

As Dave Pockley and Neville Pinder cut up the bait for the morning on the coble landing at Filey, they predicted a good showing of lobsters. The main summer fishery had moved into top gear a couple of weeks before this trip on 29 July, 2008.

A few minutes after the skippers of the cobles Gentle Barbara, Kathryn and Sarah, Lucy Anne and Energy had transferred their radar sets from van to coble and switched them on, the engine of the launch tractor coughed into life after a rolling start down Filey coble landing.

… off Filey Beach.

Dense fog was limiting visibility to 20m, so the radar and the boxed compasses, placed on the aft thwart near to the steering tiller, would be in constant use for the next few hours.

Dave Pockley fired up Gentle Barbara’s engine when the coble’s forefoot entered the water as the rapidly submerging tractor pushed the two-wheel launch bogie into Filey Bay. At the first signs of Gentle Barbara floating, the engine was put into gear and the coble eased ahead, with the fog rapidly enveloping the tractor.

As soon as there was sufficient water aft, the long rudder was lowered onto its pintles and the tiller positioned, while partners Dave Pockley and Neville Pinder looked intently into the fog to locate a visiting yacht that was anchored close inshore in Filey Bay, which is an approved anchorage.

Within five minutes, the first dahns loomed out of the fog, at the same time as the sound of the Bell Buoy off Filey Brigg could be heard. After steaming close by several dahns to find the right one, the first anchor of the morning quickly appeared at the gunwale rail aft, before the pots started to come aboard as Dave Pockley and Neville Pinder settled into their finely honed routine.

Underway, with rudder down for another morning’s potting.

Having previously fished with the Yorkshire coble Ocean Reward, the Filey partners bought Gentle Barbara WY 17 from Ernie Thomas of Redcar. Like their previous coble, Gentle Barbara was built by Tony Goodall at Sandsend in 1983.

A new 60kW Ford engine, coupled to the existing BorgWarner 1.5:1 reduction gearbox, had been installed one year before this 2008 trip. Directly driven from the fore end of the engine, a Spencer Carter hydraulic pump powered the 1t Spencer Carter slave hauler box-mounted in the middle of the aft thwart. A davit arm and hanging block were fitted on a box-section aft gantry, on which boxes housing the coble’s Furuno radar and Koden sounder were also mounted.

From the first pot, lobsters appeared with gratifying regularity. In recent years, Filey crews, along with their colleagues along the east coast of England, had experienced extremely encouraging numbers of lobsters on their local grounds. Catch rates, particularly from late July to mid-September, had generally been good. The continuing appearance of large numbers of smaller lobsters, a hugely encouraging sign for the future, was particularly pleasing.

Hauling…

Increasing the minimum carapace length from 84mm to 87mm and operating a V-notching scheme, whereby berried hens were marked and released for three consecutive years, were two of the main reasons given by skippers for the marked increase in lobsters on the grounds. The decline in trawling activity along the coast was thought to be another more peripheral factor, with small lobsters benefiting from increased bottom sanctuary in the early stages of their life.

Dave Pockley reported that, after the MLS was raised, it took 18 months for boats to get back to where they had been in terms of the number of lobsters caught. Now, however, several years down the line, the benefits were clear. The fishery was definitely better than it was, with lobsters being found in places they never used to be caught.

Having recognised the importance of sustaining and consolidating the valuable coastal lobster fishery, crews were keen to maintain the positive impetus associated with such initiatives. At the same time as carefully checking each lobster for size, Neville Pinder looked closely for signs of V-notched lobsters, which were then voluntarily returned to the seabed to aid future stock recruitment.

… and rebaiting the second fleet off Filey Brigg.

The previous year, the Filey coble had taken a scientist to sea each morning, who then implanted tags into every lobster caught and released through funding provided by the North Eastern Sea Fisheries Committee (NESFC). By recording the position of each tagged lobster caught since then, a clear picture of the movement of lobsters was being built up. Early evidence suggested limited movement, highlighting the benefits of crews maintaining good working practices on their local grounds. One regulation that some skippers were keen to see introduced was the introduction of a maximum size restriction – consumer demand for very large lobsters being limited – in order to retain a mature breeding stock.

Later in the morning, the degree of monitoring to which potters were subject on a regular basis was highlighted by the appearance on the inshore grounds of Fishery Protection Vessel Tyne. It launched its RIB a couple of miles offshore from Speeton Cliffs, a few minutes before the Whitby-based North East Guardian III steamed down from the north, before doing likewise off Filey Brigg.

After boarding Filey skipper Paul Gage’s Scarborough-based potter Cornucopia, three boarding officers from FPV Tyne, which had been fog-bound for two days off the Humber, spent an hour checking the minimum size of lobsters, before finding everything in hand and moving onto another potter.

Neville Pinder shooting away, with the Bell Buoy to port.

Shot in close proximity to Filey Brigg, the first four sets of gear yielded 37 sizeable lobsters, while half as many more were returned, a large number of which were just 1mm away from meeting MLS requirements. The partners were satisfied with this return, which came from older gear, reserved for duty on hard bottom in shallow water.

This set the tone for the morning in terms of catch rate, and the preponderance of lobsters which would be marketable the following year was particularly encouraging.

Gentle Barbara fished 20 Medley 34in parlour pots spaced at 12 fathoms on 14mm-diameter tows.

After the first hour of fishing, Dave Pockley headed a couple of miles into the southeast for the next group of gear. Although the fog persisted, a dahn carrying the WY 17 identification tag, as required by the NESFC, was located, and hauling resumed. Usually Gentle Barbara would haul stern first with the tide, but not wanting to overshoot the gear by trying to find the uptide end, hauling continued into a slackening ebb tide.

Taking a parlour pot aboard.

By now, the coble was fishing in deeper water two miles east of Smeeton cliffs, the outline of which started to become visible as heavy rain encouraged the fog to disperse. For a couple of fleets, the number of lobsters increased, with some well-fished pots yielding two to four blue beetles on a number of occasions, with throwbacks again outnumbering keepers.

Another Filey coble, Kathryn and Sarah, was hauling close by, and skipper Julian Baxter reported a similar catch rate. Two Scarborough-based boats, Cornucopia and Magic, were also fishing in the area, as was Foster Cammish’s Energy. Not surprisingly, a good number of dahns were always visible, and more times than not, a half-bucket of lobsters led to the pots being shot back again.

At 9.40am, the last dahn of the morning slid astern of the transom, after the 15th fleet of the morning was shot away. Dave Pockley then headed Gentle Barbara towards Filey Brigg, one and a half miles away to the west, with 117 lobsters boxed ready for delivery to Scarborough shellfish merchant Edwin Jenkinson.

On approaching Filey beach, after using less than five gallons of diesel, the tiller was pushed over to starboard, before Gentle Barbara swung stern-on and went astern towards the beach, at the same time as the rudder was lifted aboard. As the waiting tractor pushed the bogie into the water, Dave Pockley and Neville Pinder jumped overboard into waist-deep water to position the wheels and pull the coble firmly onto them. They then headed up the beach towards the coble ramp at the end of a typical morning’s work, which showcased the long tradition of coble fishing along the east coast of England.

End of Filey coble era approaching

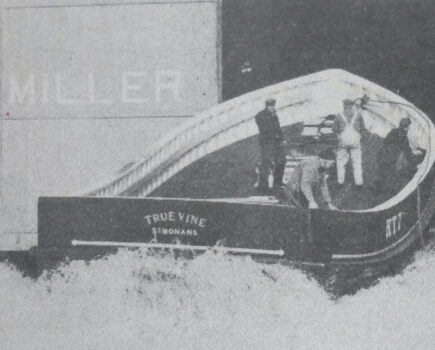

The Filey coble Lucy Anne hauling.

Generations of inshore fishermen had launched cobles off the beach at Filey, where the close proximity of the tidal Filey Brigg offers some protection from northerly seas, in stark contrast to the totally open and exposed southeasterly aspect.

Twelve years ago, four two-man crews operated four 30ft cobles from the Filey landing all year round, where they were joined in the summer months by six single-handed salmon beach boats. This number was much reduced from the 22 cobles and 11 salmon boats that fished from Filey 30 years earlier. Although interwoven, some of the main reasons for this reduction included changing lifestyles, the decline of long-lining for cod in the winter months, and the higher cost of static gear.

The local fleet were all members of Filey Fishermen’s Society, which was established to enable fishermen to operate in a challenging environment on a daily basis with maximum efficiency.

Neville Pinder measuring a lobster…

Each boat made a weekly contribution to the society, some of which was used to cover the running costs of the all-important tractor, and launch man Michael Budd. Two weeks before this trip, the society had bought a second tractor, which in addition to being newer, increased safety levels by ensuring that a reserve unit was readily available in the event of any unexpected mechanical failure.

In the years after this trip, the future of the Filey fleet became increasing precarious, due to ever-rising operational costs coupled with a declining fleet.

What had become a losing battle to retain tradition was irretrievably lost a few years later, when a severe storm washed away the sand that had made beach launching practical by covering underlying boulders. The loss of this overlying protection heralded the end of full-time cobles working from Filey coble landing, leaving only a small number of punts used during the short trout netting season.

Photos 21, 22 & 23

Traditional cobles designed around local conditions

… and throwing an undersized one back.

Cobles are a unique design of inshore boat that have been favoured and extensively used by generations of fishermen along the northeast coast of England. Pronounced ‘ceuble’ in Northumberland and ‘cobble’ in Yorkshire, cobles are often referred to as the queen of boats, reflecting the fact that they were often used to catch salmon, the king of fish.

Ideally suited to local needs, often being launched off the beach daily in the absence of suitable moorings, the design of the traditional coble has more than stood the test of time, by being readily adapted to motor power from the original sail and oar propulsion, with only minor modifications.

The longevity and reliability of cobles is shown by the fact that, although used in diminished numbers today in northeast England, due to changes in both fishing opportunities and lifestyles, the ubiquitous coble can still be found fishing at opposite ends of Britain, in northeast Scotland and southwest England, as well as many locations in between.

Sharing a number of similarities with the Norse longboats that raided along the northeast coast in the eighth century, the coble is built as a high-bowed, flat-bottomed clinker-built boat, usually measuring between 30 and 36ft long overall.

Taking a dahn aboard after steaming a couple of miles offshore, as rain starts to disperse the dense fog.

It was traditionally rowed out from the beach through breaking waves by two men at the oars and the skipper at the tiller. When clear of the surf, the sails would be set and the oars slipped. When launching or retrieving a coble, the bow is swung round to face oncoming waves, at the same time as the boat is moved forwards or backwards up a shelving sand or shingle beach.

The hull of a coble is a composite design, having an almost wine-glass-shaped forward part that sweeps elegantly back into a flat-bottomed stern. By having a deep forefoot, cobles continue to work static gear from the stern quarter, which is easier to pull through the water.

The use of a large rudder extending some distance under the coble compensates for a relatively small draught aft, and allows a coble to be controlled when running before weather. Before beaching, the rudders are quickly lifted off their pintles and taken onboard.

Cobles are built around a flat plank, the ram plank, which is traditionally made of English oak. The ram plank substitutes for the keel in other boats. In Northumberland, the length of the ram plank is considered to be the coble’s length, while in Yorkshire, the overall length of the coble is usually given some 10ft longer than the ram plank. Originally, the ram plank of a sailing coble ran straight from the forefoot to the transom stern.

The FPV HMS Tyne approaches Paul Gage’s Scarborough-based potter Cornucopia.

The upward sweep towards the transom of the flat bottom is known as the kilp, and was usually made by the boatbuilder to suit the angle of the home beach from which the coble would work.

Built by an experienced eye rather than from specific plans, cobles generally have a length four times that of their beam. The hull is constructed from broad planks known as strakes or strokes, which in larger cobles can be up to 1in thick and 12in wide. Fashioned from seasoned larch, the planks are fitted to frames of English oak.

Two baulks of oak, known as draughts or bilge keels, are usually fitted to the flat part of the stern. These bilge keels, like the forefoot, are fitted with steel coping strips, to act as sacrificial skids when dragged across beaches. This tripod arrangement also ensures that a coble sits upright when out of the water, without listing over.

Renowned coble builders, such as J&J Harrison (Amble), Beverley & Dawson (Seahouses), Tony Goodall (Sandsend), Gordon Clarkson and William Clarkson (Whitby) and John Clarkson (Bridlington), delivered a succession of cobles that, while broadly similar, were all unique, with new builds taking shape according to the preferences and experience of the builder.

Taking an end aboard Julian Baxter’s coble Kathryn and Sarah.

The split of boatbuilders between the north and south of the region is a major reason for the fact that there are two distinctive types of coble, the Northumberland coble and its equally renowned Yorkshire counterpart.

By having finer forward sections and more pronounced tumbleholme on the top planks, Northumberland cobles carry on the tradition of sailing cobles. The engines of Northumberland cobles are also located further forward, so that the balancing point, when slipped onto a bogie, is located well aft of the engine.

Yorkshire cobles are characterised by being shorter in the head and fuller forward, with all but the top plank sloping outwards.

When engines were first installed, a planked rectangular box was fitted into the ram plank to accommodate the propeller. While providing a short-term solution, this tended to create cavitation, as water flow under the hull was disrupted.

Hauling another fleet on Gentle Barbara…

The optimum answer was quickly found by curving the ram plank upwards to effectively make a convex-shaped propeller tunnel in the aft section of the ram plank, by using a mould, wedges and seven uprights bearing against the roof of the building shed.

Cobles built with engines to work from larger harbours such as Amble, North Shields, Whitby and Scarborough usually had long fixed propeller shafts. Cobles built for daily beach launching had lifting propellers, achieved by fitting a universal coupling into the propeller shaft, the aft section of which could then be lifted up by a vertical drop shaft that usually ran through the aft thwart. The use of two bladed propellers, which were always turned to the horizontal position, ensured that the propeller was fully retracted and protected by the bilge keels when being launched or retrieved from the shore.

Most cobles have a small vertical wooden tunnel incorporated into the bottom of the hull above the propeller. Unbolting the top of the tunnel, which is located slightly above the waterline, allows a skipper to lower his hand and arm down to clear stray netting or ropes that might have fouled the propeller. This task is made slightly easier on cobles with lifting shafts. Another advantage of a lifting propeller is that it enables a skipper to let a coble blow across drift and T-nets in the event of getting on the windward side of the net.

Northumberland fishermen have traditionally set characteristic canvas cuddies forward to provide a small degree of protection, enabling small stoves and mattresses to be carried onboard. These were particularly welcome in the days when salmon netting took place overnight, before the introduction of monofilament nets.