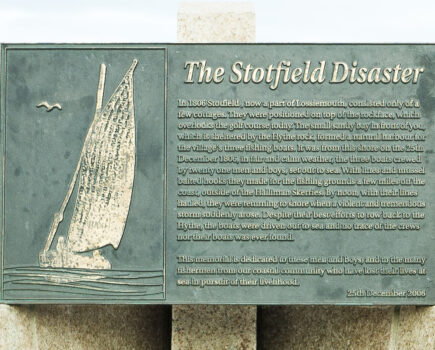

Great Yarmouth was a centre of the herring boom. Now it’s more gas and wind. John Worrall reports

In normal times, Great Yarmouth is a visitor town. Wide sandy beaches, lots of fast food and the seafront Golden Mile make for family holidays of the Blackpool-going-on-Brighton variety. When normal times return, all of that will hopefully resume – although what the new normal will look like is anyone’s guess.

Right now, Great Yarmouth seafront is furloughed, like the rest of the country.

But Yarmouth has a much longer pedigree than the other two resorts, having been a working town long before either was two sheds and a donkey, and that comes down to the standard criterion for the development of a port in ancient times – the sheltered haven.

In Yarmouth’s case, the clue is in the name – Yare mouth – the mouth of the river that meanders down from Norwich. By the time it flows through the modern town, parallel to the beach for the last three miles, it is carrying the water of two others: the Waveney from the southwest, and the Bure, which was known as the Northern river back in the commercial river traffic days.

Those three between them carry run-off from the Norfolk Broads and surrounding higher ground, much of it backing up on the flood in Breydon Water, a mudflat just inland, 5km by 1.5km at its greatest extent, from which the tidal release adds considerable velocity to the ebb through the town. That flow rate has caught a few out over the centuries, although the plughole effect of the reverse flow into the narrow, long, artificially constrained river mouth was even more tricky in the days of sail, with several fatal upsets.

The main remnant of Yarmouth fishing is the Lydia Eve YH 89, the only surviving steam drifter – see lydiaevamincarlo.com

The estuary looked very different when it caught the attention of the Romans, because the Bure had its own outfall, called Grubb’s Haven, at Caister a couple of miles to the north. The Romans built a town there, and a fort to the south at Burgh Castle, overlooking the southern end of Breydon Water, whose massive flint walls still stand.

Back then, the stretch where most of Yarmouth town now sits was an insubstantial sandspit, an island between the Bure and the Yare, and although it was firmer ground by Domesday in 1086, it still housed only a small settlement of 400 or so fisherfolk. It wasn’t much use for cultivation, and the sand hills on the seaward side, known as the Denes, were used for rough pasture and net drying – but they became the venue for the annual autumn herring fair which, at its 13th and early 14th century peak, was one of the great medieval fairs of Europe, attended by Dutch, French, Scandinavian and even Italian boats. When the town was granted its charter in 1209, herring was important enough to feature on the coat of arms.

Interestingly, herring were reckoned to have become even more numerous in the North Sea after they largely vacated the Baltic sometime in the first millennium, for reasons still not entirely explained. One – just possibly apocryphal – story is that the Vikings invaded Britain in search of their lost herring. Another has it that herring left the Baltic in 1425 (admirably precise, if a little tardy) ‘due to the Dutch having by this date exterminated the whale, which is the herring’s greatest natural enemy in the North Sea’.

But there is the wonderful Time and Tide museum…

By the time of those fairs, Yarmouth’s sandspit was becoming a peninsula with the gradual silting of Grubb Water. It supported a sizeable town, with streets running north/south between river and beach, and small lanes – ‘rows’ – running through from the Denes to the riverside, 145 of them eventually, most of them probably in place by the 12th century.

It was also a major port, a staple for the export of wool and of worsteds – a Norfolk speciality – along with herring in various forms. Wine, timber and stone came in. By 1261, it was sufficiently important to the defence of the eastern counties that Henry III authorised the building of the town wall, which was begun in 1276 and finished by 1387.

Much of the wall remains, including 11 of the 15 round towers, threading through 19th- and 20th-century development – though once it was finished, no one was allowed to live outside it, and the resultant congestion was responsible for the narrowing of those rows, down to 27in in one case. Fishermen and others navigated them in ‘troll carts’ with shafts mounted outside the wheels to measure the width and avoid damaging the wheels. Second World War bombing obliterated many rows, and others disappeared in redevelopment, but fragments remain.

The haven entrance nevertheless needed constant management. The longshore drift which had closed Grubb Water was repeatedly choking the Yare’s mouth, particularly after big northeasters, and the town had to keep digging a fresh channel. Half a dozen were cut in medieval times, one or two not lasting long, like that at Corton three or four miles to the south. The present outfall was dug in the 1560s in a combined effort by men, women and children, and stabilised with timber piling by Dutch engineer Joost Jansen.

… housed in the aromatic JRN Tower Curing Works – when it reopens.

Longshore drift even built up Scroby Sands just offshore, which in 1560 looked like becoming an island, and the town tried to annex it, sending the bailiff and his burgesses to stake the claim. But the North Sea swallowed it again two years later. Today it supports a wind farm.

However, Yarmouth life wasn’t all work and no play, and the town already liked a party. The annual Yarmouth Water Frolic, first mentioned in 1577, combined singing and jollity with the reading of legal proclamations. It ran for 400 years, despite misfortunes such as that in 1793, when the gaff of the official wherry fell and killed a guest, and in 1865, when the wherry’s hatches gave way, and those standing on them landed on those below, and several died. Both events dampened the mood a bit.

And then there was the annual election of the ‘seaside mayor’, which saw him carried around the town in a boat. Up until the mid-19th century, he controlled the beach where, latterly, sailing trawlers were landing sole and plaice, and from which, before the advent of the railways, fish were transferred to four-horse vans that took them in early morning to London, 48 horses being used for the 12 stages.

Nelson’s column, Yarmouth style. That’s actually Britannia on the top, but the sentiment stands.

That rapidity of supply from Yarmouth and other ports gave the capital’s street salesmen fresh fish all year, and helped to educate mostly meat-eating poorer folk on its merits, where previously herring and mackerel in season were about the limit of their tastes, along with that other Dickensian pauper’s option, oysters.

Nevertheless, in the 17th and 18th centuries, the Dutch were bigger than the English in the North Sea fishery. Already by the time of James I (1603-25), they had 600 to 800 boats on cod and 1,000 on herring off the English and Scottish coasts. King James seems to have been happy simply to demand 12 cod from every Dutch working vessel – which the fishermen paid, even though their government objected. The North Sea was described as ‘that principal goldmine of the Dutch’, at least until the Dutch fleet faded, reduced by the fourth – and last – Anglo-Dutch war in the 18th century, when the Royal Navy had become the premier maritime force in the world.

Thereafter, things were all sweetness and light between the two fishing fraternities, the Dutch becoming picturesque and popular visitors to Yarmouth, with the Sunday before Michaelmas known as Dutch Sunday, when people turned out to admire their visiting boats.

That premier maritime force did have its downside, however, because it took a lot of impressment to get crews, which could leave the fishing boats shorthanded. On one day in 1802, the press gangs rounded up 300 men in Yarmouth – although they did apparently try to avoid the all-important main fishing season, which was nice.

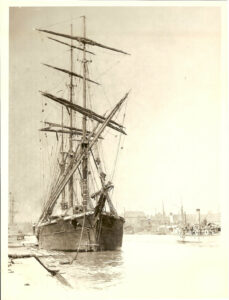

But the port was anyway full of trading ships. In the 1720s, Daniel Defoe was writing that Great Yarmouth had ‘the finest Key in England, if not in Europe’, adding that ‘the ships ride here so close and as it were keeping up one another, with their heads fast on shore, that for half a mile together, they go cross the stream with their bowsprits over the land, their bows, or heads, touching the very wharf so that one may walk from ship to ship as on a floating bridge’.

The first jetty was built about then, and rebuilt after big northeasters in 1769, 1791 and 1805, when it had become ‘indispensable to ships of war’.

Yarmouth drifters around the turn of the 20th century. Defoe, a couple of hundred years earlier, would have recognised the density, if not the type. (Photo: Time and Tide Museum)

Nelson, a local boy, landed there in 1800 after the Battle of the Nile, ‘glorifying in being a Norfolk man’, and received the freedom of the borough. “Your right hand, my lord,” said the town clerk, when he went to administer the oath and Nelson had laid his left hand on the book. “That is at Tenerife,” he replied.

It tugged a few heartstrings, and the town took a close interest in his career thereafter. In 1819, after his death, the town raised a 144ft monument in his honour, which is still there on South Denes – in the middle of what back then was a racecourse, laid out by the military who garrisoned the Denes during Napoleon’s time.

The garrison was later run by another Norfolk boy, Captain Manby, who, after watching the wreck of HMS Snipe just 60 yards from the shore, with the loss of over 200 lives, invented a mortar device for throwing a line to stranded vessels which developed into the breeches buoy. By the time of his death in 1854, it had reportedly saved 1,000 lives.

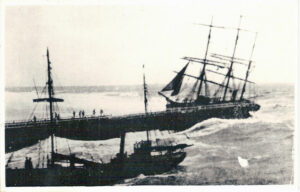

Getting into the river mouth could be tricky in bad weather, more particularly on the flood… (Photo: Time and Tide Museum)

The first keeper of the monument, an old sailor called Sharman, was said to have been the model for Ham in David Copperfield, which Dickens set in Yarmouth. And Copperfield himself was probably a typical first-time visitor, because on arrival, he saw only flatness, and observed to Peggotty ‘that a mound or so might have improved it’. “But Peggotty said, with greater emphasis than usual, that we must take things as we found them and that, for her part, she was proud to call herself a Yarmouth Bloater.”

However, Copperfield came to reconsider his opinions: “… when he got into the streets and smelt the fish, and pitch, and oakum and tallow, and saw the sailors walking about and the carts jingling up and down over the stones, he felt that he had done so busy a place an injustice.”

The first half of the 19th century, before the arrival of the railways, was the golden age of coastal shipping. Small self-contained coastal communities were a thing of the past, and goods of all kinds moved coastwise and gathered in major ports like Yarmouth. At its peak in 1843, the town had 585 ships totalling 50,000t, and they were only part of the traffic. One observer, in October 1838, noted nearly 2,000 vessels lying windbound in Yarmouth Roads. When they got underway on 1 November, they were followed by another 1,000 from the south. “In all, 3,000 sail went through the roads in five hours, so that the sea could hardly be seen for ships.”

… but ships managed – although the advent of steam tugs helped. (Photo: Time and Tide Museum)

A lot of those would have been colliers, because the east coast coal trade had been running since the 16th century, hauling coal from the North East. In 1844, three-quarters of the coasting fleet were at it, bringing 2.5m tons annually to London alone. In Yarmouth’s case, coal and other cargos were taken inland to Norwich and other communities up those three Broadland rivers by keels, and later by the more weatherly wherries.

And by then, herring had become big again for Yarmouth – pickled for export to Germany and Russia, heavily smoked to make red herring, split and smoked to make kippers, or lightly smoked as that Yarmouth speciality, the bloater, the ilk of which Peggotty was proud to be. Yarmouth schooners raced out to the Mediterranean with all of that, and came home with dried fruit. In 1845, there were 60 herring curing houses supplied by 160 luggers of 30-50t. There was also a big mackerel fishery employing 80 similar boats, and by 1883, the town had 100 mackerel boats and 400 herring luggers working from its haven, 100 of which came from Scotland.

Some had also moved up from the Thames, whose fishing ports, particularly Barking, had always had the advantage of being within a tide of the London market, and had grown on as the North Sea became safer after Napoleon’s defeat.

It was in Barking, two miles off the Thames on the river Roding/Barking creek, that Scotsman Scrymgeour Hewett had settled in 1760 and developed a fleet of well smacks – Hewett’s Short Blue Fleet, named after its blue flag. His son, Samuel, introduced carriers to bring catches in and allow the smacks to keep fishing. By the mid-19th century, that fleet had 220 vessels, not all owned by Hewett’s but working under its flag. They moved latterly from lining to trawling. Trawled cod fetched only half the price of hooked – particularly live – cod, but quantity trumped quality.

You get a different sort of kit in the river these days – mainly offshore supply ships, bulk carriers…

Unfortunately for Barking, it was also within a tide of London’s sewage, which increasingly obliged well smacks to transship live fish to carriers with tanks further downriver at Gravesend. Eventually, in the 1850s, with the railway on its way, Hewett’s fleet of sailing trawlers and drifters moved to Gorleston, across the river from Yarmouth.

There they found the fishing scene to be less advanced, still drifting for herring and mackerel and doing a bit of lining, all with crews of mostly agricultural labourers, whereas Barking had been trawling for a while, because by then, there was a new goldmine – or rather silver – known as the Silver Pit, broadly adjacent to the Dogger Bank. Discovered by smacksmen in 1843, it had overnight become one of the richest waters in the world, where a newfangled beam trawl could quickly fill with prime sole.

By 1872, the Yare mouth was by far the biggest fishing centre on the East Anglian coast, with 493 Class 1 – over 15t – boats and 462 Class 2 – under 15t – and a railway connection that got the product quickly to London, even if that quantity over quality didn’t please everyone. In the 1860s, The Field was complaining: “Since the extension of the railway, nearly the whole supply to Billingsgate is from dry bottom boats, and to this cause is attributed the decline in quality which is lamented by all gourmands.”

… and miscellaneous big beasts…

And just as steam had transformed inland transport, so in the 1880s did it change the tempo and efficiency of the herring fishery, building to a peak in 1913, when 1,650 vessels landed about 800,000 cran of herring (37.5 gallons, and specifically a herring measure), or about 2,000,000,000 fish, at Yarmouth. On 23 October, 1907, nearly 80 million herring were landed in one day, then gutted and packed in brine-filled barrels by Scots girls, who famously followed the herring migration south each autumn.

Meanwhile, Yarmouth had become a resort, mostly developed in the 19th century to cater for straw-boatered Victorian upper and middle classes who came for the summer – though they were replaced between the wars by less posh parties coming for a week or less.

But the First World War, along with the Russian revolution, stopped the herring fishery dead. It cut off the major German and Russian markets, and many boats were anyway commandeered for anti-submarine and mine clearance roles. An already overfished stock failed to recover on their return, and by 1960, herring catches were down to 2-3% of the peak. The last Yarmouth steam drifter was sold in 1963, and shortly after that, the first drilling rigs began searching for gas off the Norfolk coast. Yarmouth, with a river giving tugs and supply vessels 24-hour access, was ideally placed as a base for offshore industry.

… which can cause trouble. The Breydon Warrior got trodden on in 2007.

Hardly anyone fishes from Yarmouth now. The port added an outer harbour a decade ago adjacent to the river mouth, and that and the river quays are filled with supply vessels for the oil, gas and, increasingly, the renewables sectors, along with cargo ships, mostly bulk carriers. They don’t make comfortable company for diminutive fishing boats, as the Breydon Warrior found out back in 2007. That 25-year-old Napier 37, recently refitted to switch from commercial fishing to pleasure trips out to the Scroby wind farm, was crushed against the quay on the Gorleston side by a supply vessel manoeuvring in the swirl of a big ebb. Fortunately, no one was aboard.

All that’s really left of Yarmouth’s fishing heritage is the world’s only surviving steam drifter, Lydia Eve YH 89, usually moored near the Haven Bridge, open to the public and doing occasional passenger-carrying trips – in normal times, anyway. But there is also the wonderfully comprehensive Time and Tide museum, which covers every aspect of Yarmouth fishing – again, in normal times – right down to the smells, because it’s housed partly in an old smokehouse.

Oh, and there is a seafront pub called the Barking Smack – but that’s not open right now either.