Mark Blanchard looks back at the eventful 115-year life of the Cornish lugger Happy Return – virtually rebuilt twice, rescued from decommissioning and now saved for posterity

Happy Return in her 12th decade, sailing off West Cornwall.

Standing on Penzance quay, watching the beautiful profile of the Cornish lugger Happy Return sailing past the backdrop of St Michael’s Mount, you’d be forgiven for thinking she had spent all her life in the area – part of the long-term fixtures and fittings. She tells an exciting story, and boasts one of the most historic small-boat pedigrees in the UK fishing industry.

She was built at Kitto’s yard in Porthleven for Folkstone owners in 1905 to replace the Good Intent, which had been lost the previous year in a storm whilst mackerelling off the Kent coast. With a build cost of just under £180, the Saunders family named their new vessel Happy Return – a reference to the safe rescue by lifeboat of the Good Intent crew the previous year, in atrocious conditions.

Happy Return in Folkestone harbour shortly after being built.

Registered in Folkestone as a 38ft dipping lugger, Happy Return was built of sawn oak frames and pitch pine planking, and weighed just over 18t. Her main fishing was trawling, with winter longlining for cod, which was a lucrative fishery in the area at the time.

During the First World War, the Happy Return continued to fish, despite the massive dangers. On the day war broke out, harbour masters were instructed to call all working fishing vessels back to port, but this was a short-lived instruction as fish became a vital source of protein for the nation.

After the war, she continued her successful fishing career. In the Second World War, the Happy Return took part in Operation Cycle, shortly after the Dunkirk evacuations, helping to rescue troops from Le Havre between 10 and 13 June, 1940. She is honoured on the Association of Dunkirk Little Ships list, and is entitled to fly the association flag.

Homeward bound to Folkestone after a day’s trawling.

Fishing from Folkestone was very dangerous during the Second World War, given its proximity to France. Trawlers working from the port became easy targets for German Messerschmitts as they headed for the south coast. Some fishing boats carried Lewis guns on deck, but this further provoked the pilots, so they were removed. The famous ‘Kipper Patrol’ squadron, headed up by RAF Coastal Command, was instrumental in saving many fishermen’s lives.

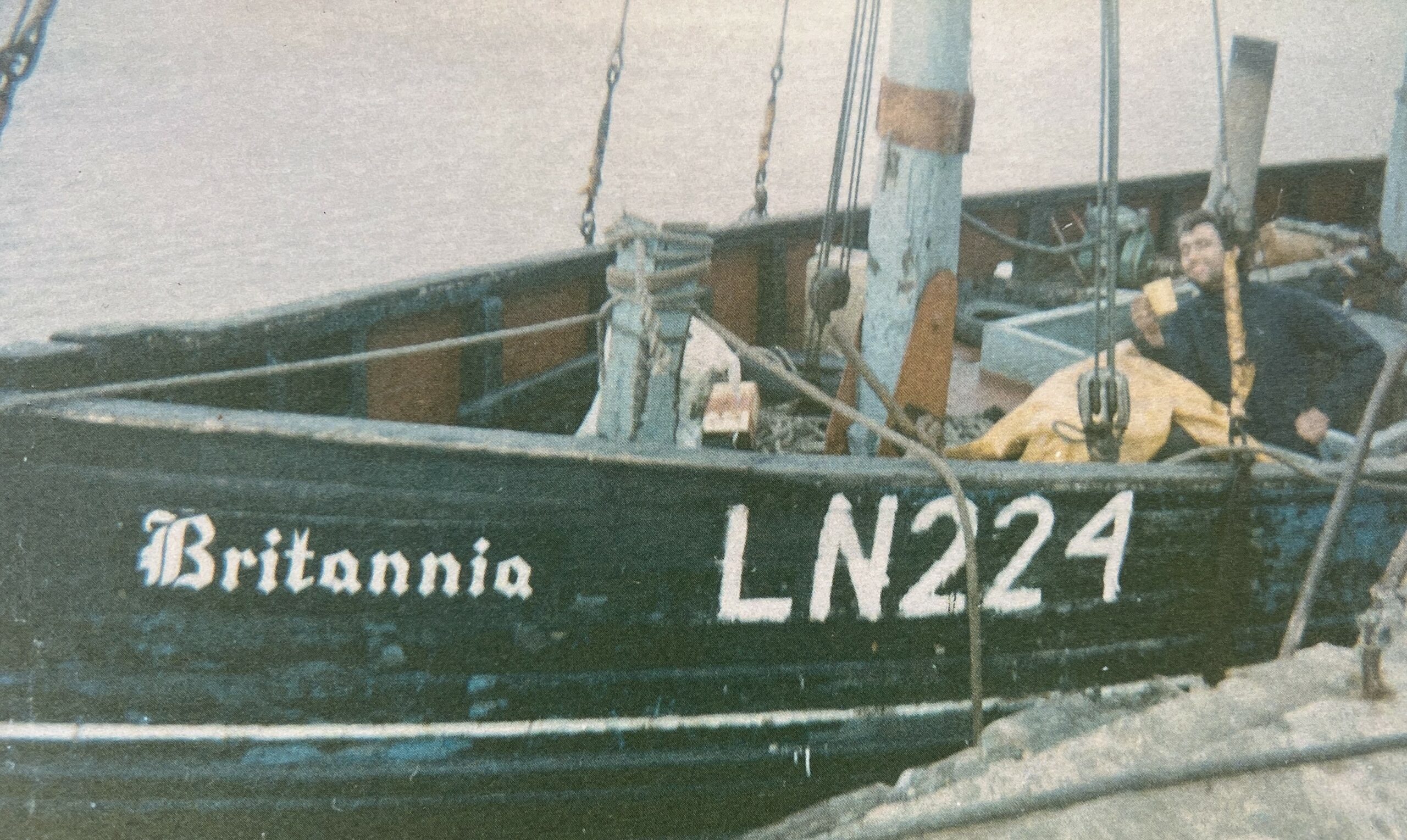

Following the war, records show that the Happy Return continued fishing from Folkestone under different owners, became motorised, and had a hauler fitted. She then moved to the east coast, underwent a name change to Britannia, and was registered LN 224.

A new colourful phase of her career began in the early 1970s, when Dorset-based commercial scallop diver Peter Barratt decided to upgrade from his Zodiac rib to a more conventional fishing boat to allow him to diversify.

Happy Return moored in Folkestone harbour.

The inshore industry was booming at the time and boats were in short supply – after scouring the Fishing News classified for months, only two 40ft boats had come up for sale.

Peter was in London visiting his parents for Christmas 1970 when he spotted the ad for Britannia. He immediately contacted the owner and arranged to view her in King’s Lynn straight after Boxing Day.

The weather was awful, with freezing fog, black ice and sub-zero temperatures, which added hours to the journey. When he eventually arrived and saw the vessel, he decided he needed a second opinion and a survey before committing to buy.

He went back to Dorset and spoke to fellow fisherman and qualified shipwright Michael Brown, and it was arranged for the Britannia to be beached on legs so they could have a good look at her below the waterline. They did the 500-mile journey there and back in a day in Peter’s A35 van, in a hard frost with no heater – a day, Peter says, that most certainly changed his life.

Michael Brown at the wheel of the Britannia on the voyage between Dover and Poole.

He agreed on a price – but he now says, on reflection, that he actually ‘paid a very expensive debenture to a shipwright and boatbuilding apprenticeship which lasted 27 and a half years’.

The deal was that the vendor, Mr Rake, would sail with Peter back to Poole Harbour on the delivery trip, in case there were any teething troubles – which was where the next stage of the adventure began.

Peter’s log and passage plan starts on 16 January, 1971: “Ready to sail, weather improving – shipping forecast, Humber Thames Dover variable 2-3, fog patches – Rake unable to join for personal reasons – good day lost.” I think alarm bells may have already started ringing about his investment.

They got underway the following day. Within hours they had stopped several times with water pump and overheating troubles, but they were just about nursing her along. The weather had turned for the worse, with thick freezing fog.

They set course for the North Goodwin Lightship, with Peter taking the watch, when Mr Rake came up from the engineroom to inform him they were losing oil badly. Peter decided to go alongside the lightship, borrowing five gallons of oil to keep them on passage. This was, apparently, the highlight of the day for the light vessel crew, but they were disappointed the Britannia had no fish onboard to barter with.

Peter Barratt (left) and Michael Brown on deck.

Continuing on their way, further engine trouble hit – the revs kept dropping and they diagnosed a fuel pump problem. Peter decided to head in to Dover – by this stage, reality was setting in about his new purchase.

Undeterred, he went ashore to find a marine engineer. On his return, he bumped into Mr Rake running along the quay with his suitcase on the way to the railway station.

At 6am the following morning, Peter woke to find water lapping up around his bunk – the engineroom was fully flooded, along with the fishroom. It took a full two and a half hours with the pump at 1,800 litres an hour to get her dry. The engine needed to be completely flushed.

Michael Brown came up to Dover, and they spent the next two weeks making the vessel shipshape for the next and hopefully final leg of the voyage.

Peter in a rare moment of calm during the early days of ownership.

The weather settled, and they left Dover. On the passage past Dungeness towards Royal Sovereign, the engine started to feel extremely hot, so they slowed down, and then the clutch plates started slipping in the gearbox, causing a loss of propulsion.

Coupled with this, she started to make water badly, and the wind was again freshening. They put up a red flare, and were towed into Newhaven by lifeboat. Things got so bad that Peter was in the hold bailing with a bucket to help the pump out to keep her afloat.

Peter – by now realising what youth and enthusiasm had got him into – had the Britannia up on the slip at Cresta Marine at Newhaven, and made further repairs to the hull, before setting out for Swanage two weeks later, and then on to Cobb’s Quay boatyard in Poole, in flat calm sea and brilliant sunshine.

The Britannia at Cobb’s Quay, with the replacement of the transom underway.

The complete voyage was undertaken using a single compass and admiralty charts – there was no electronic navigation equipment aboard whatsoever.

And now the real fun started. The next year and a half was spent almost rebuilding the Britannia, restoring her to the fine and seaworthy vessel she once was.

Peter embarked on a crash course in shipwright skills under the mentorship of Michael Brown, who – apart from the financial burden – shared the journey with him from day one. Peter says: “Without him she’d be firewood, and a great loss to British maritime history, earned in her various roles over many years.”

The hull was completely dry-scraped to remove all tar, with both garboard planks and the transom replaced. All the original fixings were suffering nail sickness, so she had to be totally refastened using 5in, 32-gauge galvanised screws driven in with a brace and bit. The original nail holes had to be dowel-filled.

The engine beds were beefed up, and a new six-cylinder Parsons Ford Barracuda 108hp replaced the 45hp Ailsa Craig engine. The hull was fully recaulked, and new deck planks replaced rotten timber.

The gunwales were completely recapped, and four new fuel tanks were fitted, along with new deck boards in the hold. The wheelhouse underwent refurbishment, with a new hatch cut into the engineroom and the steering upgraded. She also had new stern gear and a 28in propeller fitted.

A model of the Britannia in a glass bottle, with Peter in oilskins by the wheelhouse.

After 18 months of blood, sweat, toil and near tears at times, she was ready to relaunch. Peter says: “It was a long 18 months. My skin grew thick, so many people walked past watching me work on her and thinking I was mad.

“There was one guy who boosted my morale daily – Horace Hoare, a real old Poole character well-known for his naval vocabulary, who’d sailed on several working tall ships, and worked as a rigger in the yard.

“He’d walk past every day with his trolley, go to the bow, close one eye, and cast the other down the Britannia, telling me what a great job I was doing. It really helped.”

Armed with a Mark 5 Decca Navigator costing £12 per week, later replaced with an updated Mark 12 version purchased from Navy Surplus, Britannia came back down the slip and started work.

For the first 10 years, Peter used the vessel for salvage metal recovery from wrecks, winter trawling in Poole Bay and, later, scallop diving off the Lulworth Banks.

Peter Barratt – now in semi-retirement and working an inshore netter.

Not many years after all the work, near-tragedy struck one afternoon – Britannia was on her swing moorings in Swanage when a speedboat that had lost control went straight into the side of her, piercing an 18in hole just below the waterline. Peter, who was ashore, was alerted to the disaster and immediately headed to the Britannia, which was fast making water, whilst other craft rescued the speedboat crew.

Quick as a flash, Peter jumped aboard and steamed her straight up the beach alongside the pier. Luckily, the tide was dropping, allowing the vessel to be temporarily patched up, before another trip to Poole Harbour Boat Company at Cobb’s Quay to repair nine damaged planks.

In the mid-1980s, Peter switched to mid-Channel potting, and was often seen steaming 20 miles home not just under engine power but with an original sail up – the only sailing boat in the Channel with 10 tea chests of crab aboard.

Happy Return on the slip in Cornwall under the new command of the Mount’s Bay Lugger Association.

During his ownership of the boat, Peter undertook a number of rescues, ranging from an 8ft fibreglass dinghy awash in Peveril Point tide race to a 60ft yacht on the rocks at St Alban’s Head, receiving three ‘nice’ salvage awards – which helped to pay for the expensive ongoing maintenance work.

The 1987 hurricane brought the next major issue – Britannia dragged her winter swing mooring in the South Deep at the entrance of Poole Harbour and grounded on Stoney Island, a gravel bank exposed at low water.

Happy Return off Old Harry Rocks, being sailed from Penzance to Folkestone by the Mount’s Bay Lugger Association in 2005 on her 100th anniversary.

Peter was there at first light, but it was too dangerous to launch a dinghy to get to her, so he had to wait for the wind to drop. Over the next week, he removed 3t of ballast, which allowed her to be floated off on the next high-water spring and towed yet again to Cobb’s Quay.

After a further four months in the yard, she was again ready to go back to sea. This time she had renewed hydraulic steering, and a slave hauler had replaced the capstan. When he returned to the Channel to find his gear, he discovered that the hurricane had cost him dearly, losing 100 pots.

The restored vessel alongside Penzance Quay.

In 1998, after 27 years of ownership, Peter decided to take advantage of the latest phase of the fishing vessel decommissioning programme, and made an application to have the Britannia removed from the register and surrender licences.

With the massively escalating maintenance costs of looking after an old wooden boat, along with the horrifying prospect of the structural improvements the MCA now required to allow her to continue to work as a commercial fishing vessel, Peter saw this as his – in his own words – ‘get out of jail free card’. As the Britannia was reputed to be the oldest 40ft fishing vessel still working in the UK fleet, when word got out that she was heading for decommissioning, several private intermediaries approached Peter in a bid to purchase her. He was very keen to pursue this, as it would save her from being cut up – but the decommissioning process was now underway.

Happy Return off the Scilly Isles.

The Grimsby Fishing Vessel Heritage Centre contacted Peter in a bid to take ownership, but was limited on funding. There followed some intense negotiation between Richard Busshell, the Poole MAFF fishery officer, his government seniors and Stuart Gillies of the heritage centre. All parties were in favour of saving the boat, but making an amendment to the decommissioning papers involved jumping through multiple hoops at pace.

In the last minute of the eleventh hour, Peter signed the papers in the Poole MAFF office, which were then faxed to all relevant departments, followed by frantic phone calls to check the faxes had arrived. The Fishing Vessel Heritage Centre took over the Britannia for the princely sum of a single peppercorn, and Peter received his grant for removing the boat from the industry. She was in good hands, and ready to set sail on her next voyage – which ended up being back to Cornwall.

Shipshape after 115 years, keeping her way in a following sea.

The Mount’s Bay Lugger Association had been formed with a mandate to acquire a historic working lugger to restore and sail in the area. The Britannia coming along five years later fitted the bill perfectly. The association negotiated responsibility for her with the heritage centre in Grimsby, and she was duly sailed to its yard in Penzance by Peter and his crew.

After undergoing a four-year restoration, she is now fully operational and back to her new-build glory of over 115 years ago – and, what’s more, she’s gone back to her original name, Happy Return!

Thanks to Alan Taylor of Folkestone Fishermen’s Museum and James Walker from Mount’s Bay Lugger Association for information and the use of photographs.

Find out more here.

This story was taken from the archives of Fishing News. For more up-to-date and in-depth reports on the UK and Irish commercial fishing sector, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.30 here.