Yorkshire beach-netters have cause for complaint. John Worrall reports.

And here’s another bit of administrative daftness.

On the Holderness coast of Yorkshire, there is a commercial fishery that ticks just about every box that anyone with a feel for the environment could ask for. There are just five licences, the fish is all sold within 20 miles of where it is caught, and the fishing effort itself is the final dimension of small-scale and low impact – it doesn’t even use boats.

Step forward the Holderness beach-netters.

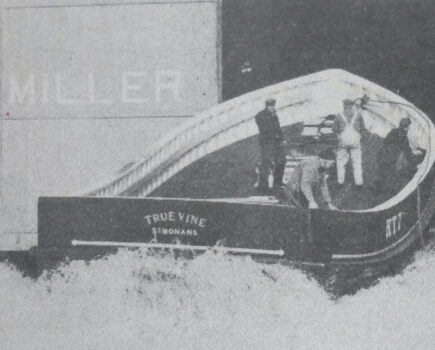

Scattered along 25 miles of coast between Bridlington and Withernsea, these five netters each shoot a 100m fleet – sometimes two – of 3m-deep net down the beach to the bottom of the ebb, floated to hang, anchored at each end and with bracing lines to angle-irons half way, the whole set-up fitted with cetacean pingers, and they catch any fish that happens along.

Beach netting on this coast goes back a long way, with its roots partly in the coble-attended ‘T and J’ nets of the summer salmon and sea trout fishery, targeting fish heading to rivers to spawn. That fishery, subject to a licence administered by the Environment Agency, continues for now, but is facing closure after the 2022 season.

Holderness beach netting was developed as a complementary fishery, allowing fishermen to target abundant sea fish in the region using similar techniques. The licensing regime for this emerged in the early 2000s out of a review by the old North Eastern Sea Fisheries Committee (NESFC) and the Environment Agency, of all beach netting activity from the Humber to the Tyne. It was a stretch that had become inundated with hobbyists using scruffy bits of net that were often left unattended for days. The review, with input from local councils, concluded that there were five legitimate commercial operators who could demonstrate a track record with catch records and sales notes, and so they were given a licence, issued and administered by NESFC. Notably, four out of the five original fishermen are still active.

The fishery runs from October through until April, with catches and species varying with the season, from winter cod, through bass and skate to spring sole. With a nod to the importance of sole, licence holders have a further derogation for May and June, allowing them to use a shallower, metre-high, net over which sea trout and salmon can easily pass.

But, gradually, bass had become more important. Almost unknown and certainly unloved in these parts 30 years ago, it had come increasingly into the picture, spreading into the North Sea, filling the estuaries with schooling juveniles, which duly fed into the marketable stock. Along with sole, the bass stock had increasingly underwritten the viability of this lowest of low-impact fisheries, more particularly as cod had become less plentiful.

This was a fishery that indeed ticked all the sustainability boxes. In fact, so pleased was DEFRA with the whole concept that, keen to flag up a sustainable management model, it funded the beach netters to go through MSC certification. With EU retailers increasingly embracing the MSC concept, here was a fishery that couldn’t have less impact if the fish walked ashore.

With certification achieved in 2007, the fishery was promoted all round Europe (notwithstanding that its landings were only enough for a very local market), TV chefs homed in, there was cooking on the beach, and dollops of administrative wellbeing all round.

As it happened, MSC certification then lapsed because five fishermen between them couldn’t afford tens of thousands of pounds for the five-yearly monitoring cycle, but that was okay because there was still only enough fish to supply a local market. The ’Fishing Five’ simply went back to business as usual, making a decent living out of supplying shops, restaurants and consumers in the immediate hinterland.

But then European bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) became an issue for the EU. Suddenly loved by consumers, it had been increasingly pursued, not least by trawlers, singly and in pairs, scooping through the North Sea and the Channel in particular, to the point where it was easy to imagine that the labrax stock might be heading for the proverbial cliff edge.

From about 2012, the scientists within the ICES network were ringing alarm bells, saying that the stock was being hammered unsustainably, and by 2016 they were recommending zero catch. The fact that the ICES recommendation was – and remains – based on uncertainty and in many respects pure supposition (not least because landings are very difficult to monitor, while discards, once they became necessary, impossible – and there go the two strongest stock level indicators) has been a point of argument for a few years now. But ICES can’t be blamed for that, insofar as they can only do as much research as the politicians will pay for, and definitive work is hugely – probably prohibitively – expensive.

The EU hasn’t yet opted for zero catch which, for the inshore fleet of the southern North Sea, let alone the beach netters, could have been a saviour. A few bass with a first sale value of £10 to £15 a kilo make the difference between profit and loss on some days, more particularly as cod retreats north increasingly from the warmth.

Except, of course, that at the last December Council, the EU introduced draconian measures, limiting targeting effort to lining and otherwise allowing a by-catch of only 250kg a month to netters – in ‘fixed’ nets – and only for those with bass track record backed by sales notes, which immediately cut out those low-impact operators who had only sold direct locally in permitted amounts of 30kg or less, though the beach netters still had their track record.

But the EU also banned commercial fishing from the shore…

It probably took a while to sink in along the flat Holderness beaches, because surely it was one thing to stop anglers cashing in and draining the stock – the stated reason – but quite another to hit an already licensed fishery that DEFRA had once funded through to MSC certification.

When it did sink in, it produced what must have been an unprecedented situation in which the North Eastern IFCA and DEFRA, together with the local MP Graham Stuart, all supported the netter’s request to the EU, asking for special dispensation for this minute fishery that was once held up to Europe as a beacon of good practice. It needed bass in order to survive. It then turned out that it was an oversight. The fishery had simply been forgotten about.

Doh.

However, the EU declined the dispensation request, and that’s how things are right now.

Fishing News went to Holderness to see what it means on the ground. Two of the licensed netters told the story.

One is Frank Powell, who also has a fish shop and restaurant on a large holiday park somewhere south of Skipsea. His fishing career started several decades ago on trawlers, and went through various boats and fisheries until he became one of the original five beach netters. “From wheelhouse to wheelbarrow,” he says, the latter being how he gets fish off the beach if there is too much for the box on the quad bike, although that doesn’t happen much these days.

The other is James Wood.

Now James brings a different and new perspective, because not only is he a licensed netter – though, unlike Frank, without a T and J licence to work in the summer – but he also has a doctorate in fisheries and spent the past decade working on sustainable management. He currently splits his time between beach netting and working on fisheries development projects, so it might be said that he knows how administrative things are run and has a view on how they should work.

On a balmy late autumn morning, in the first light of day and an hour before low tide, we put on our waders and went down through the gap in the low, crumbling cliff – this coast is eroding faster than any other in the country – and along to Frank’s net. He sometimes sets two, but if the weather has stirred up weed, there is barely enough time to clear one before the tide gets back above wader depth. And he goes down at every low tide, night and day – ‘it can be a bit lonely at night’.

The tide was still covering the bottom stretch of net, although the flatness of that lower part of the beach meant that the top half hadn’t been exposed for long. Going first to the lower section, still in two or three feet of water, Frank straightaway located a live bass which he extricated and released to swim off, and then he moved back along the net and began to take the dead fish.

It wasn’t a big catch. There were seven more bass, all over the 42cm MLS, together with two soles, a mullet, a spottie dog and miscellaneous flatties, which collectively filled less than half the box on the quad bike – not including the dead bass, of course, because they had to be thrown back.

Videos of discarding proliferate on social media, and it’s something netters see and do every day. But to a fishing hack less inured, it does look ridiculous, redolent of blunt regulatory instruments wielded from afar on the back of precaution based on science which, for want of funding, could well be 10 years behind the curve.

But that’s the way it is and the fishery will try to continue without bass, although the licence will now cost money.

“The licence has to be re-applied for annually,” says James, “but from next year it will cost £500, and, as matters stand, we won’t have bass.”

In 2015, the IFCA revised the byelaw to take out the need for anyone applying to have a T and J licence, because the EA was phasing out the latter, and everybody wanted to keep this fishery going. But all five would prefer the IFCA to take full control anyway.

“It ought really to be changed into a sea fishery all the year,” says Frank. “It’s so simple. The IFCA could run it. We don’t want salmon because we just don’t catch them, and only have a small run of sea trout, which aren’t an issue.”

James agrees. “We’re basing our businesses around sea fish. So we’d prefer to see it go into full IFCA management year-round, rather than having this joint system at certain times of the year.”

But that still doesn’t address the bass issue.

“When we heard there were to be emergency measures, we had dialogue with the IFCA, with DEFRA, with CEFAS, MMO – everybody appropriate who was involved in making those decisions, And yet when it came to the December Council and they introduced this no-commercial-fishing-from-the-shore, they forgot us and they admit it that it was an oversight while trying to deal with the angling sector.

“Afterwards, local MP Graham Stuart and the IFCA supported our push for an amendment, but by the time DEFRA put the amendment forward, it was July. Then, in late September, we were told that Europe wouldn’t consider it because they had advice that bass stocks were still in a bad state.

“And yet some local charter boats say that schoolies are so thick they have trouble getting through them, and there are massive shoals of juveniles in the Humber.”

So while that is going on, and while trawlers all across the North Sea are picking up bass by the tonne and discarding it dead without record – and thus with no input into stock level assessments – five fishermen picking up half-a-dozen per tide are stopped from retaining them for fear of depleting the stock.

“We work this mixed fishery within a very tight technical framework,” says James. “We are only allowed a limited amount of net, shot from the beach in a certain way, using set mesh sizes, at certain times of year. We have no opportunity to diversify into anything else because we don’t have boats. We have one type of fishing gear, and the fishery is governed by the depth a man can wade. We land everything to a licence, and it’s a complete mixed fishery. All we want is to be treated the same as other commercial fishing businesses.”

Ah, but then there is, of course, an upcoming window of opportunity for our politicians to have another go. Fisheries minister George Eustice and team will shortly head off to this year’s December Council.

So here’s your chance, George: bung it in under AOB – a 30-second presentation, quick show of hands, flash of the pen, job done.

After all, if the EU can give a derogation to a hundred or more pulse trawlers for scientific research, a level which ICES says is ‘not justified from a scientific perspective’ – and with no science apparently being done anyway, despite overwhelming anecdotal evidence of widespread destruction – then they can let five beach netters have a few crucial bass that have been denied to them only by oversight, more particularly since they would have them anyway if only they used boats.

Yes, Minister?

Read more features from Fishing News here.