Outsiders to Hull’s fishing community in its trawling heyday were often curious about what was nicknamed the ‘fishermen’s uniform’. But what gave rise to their unique style?

By Alec Gill

During the years after the Second World War, there was a Hull expression: “You can always tell trawlermen in town.”

That was simply because of the way they dressed when ashore in their made-to-measure suits. A striking feature was the young trawlerlads’ very wide, baggy bell-bottom trousers.

The sailors (in both the British and US navies) wore wide bell- bottomed trousers for life-saving reasons. That is, if they were swept into a raging sea, they could easily pull their trousers down over their footwear. Equally, when scrubbing the decks, they could be rolled up out of the way. This is Ted Rilatt ashore during the Second World War with his son Edward Spencer Rilatt IV.

Every industry has an identity – some stronger than others. Hull’s fishing heritage was built upon hard and perilous work. Arctic trawling was tough. Men were macho. Afloat or ashore, their image reflected their role. Young lads entering the industry and eager to succeed wanted to make an impact.

One way in which they asserted their distinctiveness was the way they dressed during their brief time ashore. Yes, it was to impress the local Hessle Road girls, but there was also a hidden, deeper cultural process at work.

When I was giving talks, I sometimes asked audiences about the origin of the trawlerlads’ bell-bottom style. The popular response was that the wide trousers were copied from sailors’ Royal Naval uniform with big, flapping flares. After all, many trawlermen did their National Service aboard HMS vessels in both world wars. This seemed a reasonable comparison to make.

Early in my research, I was swayed by this false reasoning about the strong naval influence. The truth of the matter, however, was much more colourful. Their style was not shaped by any patriotic pride, but rather by Hollywood movie depictions of rawhide cowboys and their wide leather chaps, worn on the cattle ranches and rodeos of Texas.

Fashion-wise, the trawlerlads’ nearest rivals in the city-centre pubs, during the 1950s and early 1960s, were the Teddy Boys. In stark contrast, they wore narrow ‘drainpipe’ trousers. Generally, their style followed elements of the Edwardian period – thus ‘Teddy’ Boys. Gangs of Teds were noted for their violence. Inevitably, they clashed with the fishermen, and pub brawls were not unknown.

The trawlerlads’ distinctive fashion went beyond their wide bell-bottoms. The trousers were held up by a neat 3in Spanish waistband. Their double-breasted jackets usually had half-moon pockets. One fisherman described these as ‘like the cattlemen had in their leather waistcoats’. Sometimes the pockets had different- coloured piping from the rest of the material to highlight the shape. The jacket had pleats and a Van Dyke back with a half belt.

Their white shirts had a semi- or stiff-starched collar. Some wore a tie, or even a dickie bow for a laugh. Some trawlerlads wore black suede casual shoes with square toes – the joke being ‘so you could stand closer to the bar’.

Another feature of the lads’ flamboyant fashion was to go for bright or light-coloured materials such as silver-grey, cream, white and, in extreme cases, yellow or pink! But the most popular colour was powder blue – nicknamed ‘deckie-learner blue’.

Each suit was made to measure at shops like Waistell’s on Hessle Road, opposite the fishermen’s famous Rayner’s pub. Tailor Len Pearson recalled how some of the men were ‘a bit tipsy’ when they came to be measured for a suit. He added that most of his customers requested bell-bottoms between 24in and 28in wide.

Tailor Len Pearson – who owned Waistell’s before it finally closed in around 2010 – told me that the widest ever bell-bottom he made for a trawlerlad was 30in – ‘this being the maximum width that could be cut from a standard length of cloth’.

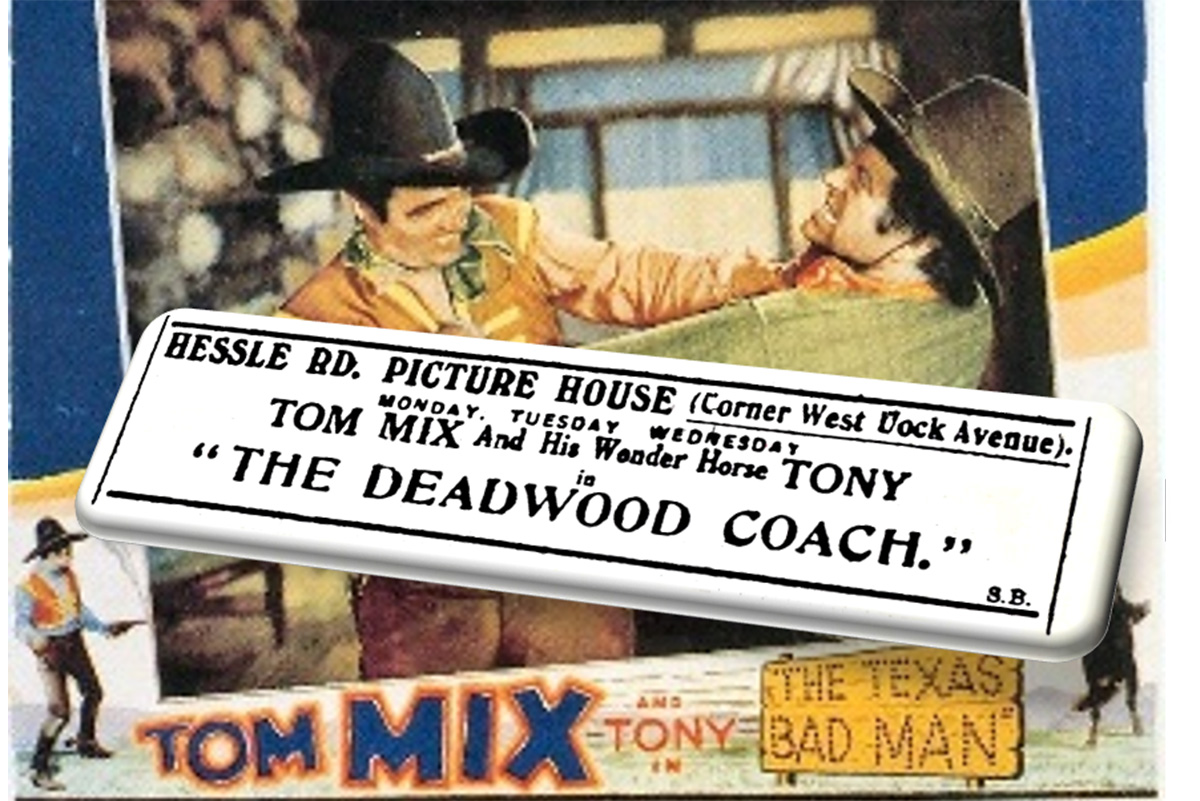

Rowdy Saturday matinees featuring Hollywood’s singing cowboys had a marked impact on the young Hessle Roaders. Each cowboy was linked to his loyal horse and a popular song. Some of the big stars were: Roy Rogers and his horse Trigger (with the song ‘My Four-legged Friend’), Gene Autry and Champion (‘Home on the Range’) and Tex Ritter and White Flash (‘High Noon’).

In the early 1930s, silent- movie cowboy star Tom Mix actually came to Hull on a promotional visit. Astride his ‘wonder horse’ Tony, Tom rode from Paragon Station toward the fishing community. His first ‘watering hole’ was the Wassand Arms, where he guided Tony through its big double doors into the pub. From this saloon, he blazed a trail along Hessle Road, lined with fans and onlookers, to the Eureka Cinema.

Tom Mix made a grand total of 291 Hollywood films – mostly in the silent era. Two of these are shown above, but another, made in 1909, was called The Millionaire Cowboy. This title probably struck a chord with the trawlerlads because they were sometimes nicknamed ‘the three-day millionaires’ when they had lots of money to spend during their short time ashore.

Next, rider and horse clattered into the picture palace to the wild cheers of the Saturday matinee kids. The young boys (some of whom went on to become top skippers) watched with excitement as brave range- riding hero Marshall Mix blasted away with his six-shooter.

Tom Mix was not a singing cowboy. Other movie characters (and their horses) in that camp included Hopalong Cassidy (and Topper), The Lone Ranger (and Hi-Yo Silver), Wild Bill Hickok (and Buckshot), Jesse James (and Black Nell) and Buffalo Bill (and Brigham). The list is endless, and these stars of the screen no doubt provided role models as the youngsters played their games of Cowboys and Indians around the back streets of ‘Dodge City’ (aka Hull).

The American culture also influenced the crewmen’s reading material. Skipper Dick Taylor noted that of all the paperbacks taken to sea, ‘cowboy books’ were the favourite.

Some men got through 30 or more westerns per trip. Various trawlermen told me about a young enterprising lad called Ernest Cooper who sold western paperbacks to the crewmen.

He latched on to a niche market in the book trade. Ernie had an enterprising spirit and went to his customers. He pushed a barrowload of second-hand paperbacks down to St Andrew’s Fish Dock at most high tides. These he sold to trawlermen about to sail off on a three-week trip.

He was also there to buy books back from other trawlermen returning on the same tide. But many a generous crewman just gave a pile of westerns back to him. It sounds as if he was on to a good thing, and would have done well in the world of business.

There is, however, a sad ending to this tale. Ernie fell into the lock-pit and drowned. His younger brother Charles then took over this fish-dock book trade. And so the trawlermen continued to get their cowboy books to read when heading out or steaming home from the Arctic fishing grounds.

Then there was country and western music. Ron Haines was one of the ‘sparks’ (radio operators) who often played music to the trawlermen at the deep-sea grounds. He regularly took about 40 of his own country and western tapes on each trip. He played them on a big Grundig reel-to-reel tape recorder that was wired to speakers in all parts of the ship: mess, crew quarters, engineroom, and from the bridge to the men gutting on the open deck.

In the ‘land of the midnight sun’, well inside the Arctic Circle, one can imagine a karaoke chorus of Hull trawlermen backing Hank Williams (‘Your Cheating Heart’). If Ron had good settlings, he often bought himself four or five new reels to share with the lads on his next trip. He said: “With a bit of music, life goes along smooth. A happy crew makes the ship run better.”

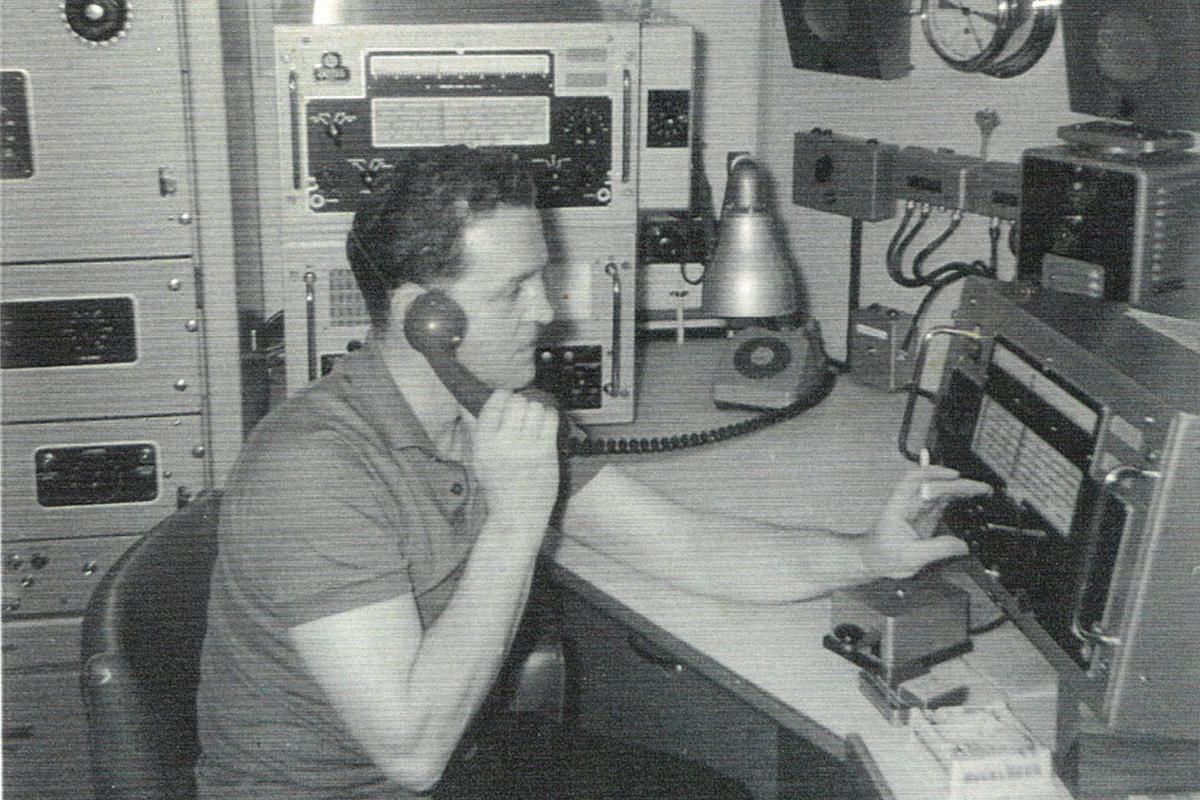

Another radio sparks, Bob Laing, recalled how Patsy Cline was the deckhands’ sweetheart. He often took several of her tapes to sea. Skipper Jimmy Williams recalled the deckhands singing in the fish pounds – he called it a ‘bobbers’ opera’. The deckhand sang along as they worked. Provided, that is, there was not too much fish to gut. When the men moaned at a mountain of fish, one skipper gleefully shouted from the wheelhouse: “Why aren’t you singing, then?”

Radio operator Bob Laing, when he was sparks aboard the Ross Illustrious H 419 in 1966. He told me: “If a fisherman got his favourite record as loud as you could get it, then the gutting went quicker – it was wonderful.”

Johnny Cash was very popular. He was a tough-looking guy who sang sentimental songs – someone once summed him up as ‘I’m a MAN, but I love my mother’ (‘Don’t Step on Mother’s Roses’).

Some of the other favourite post-Second World War singers were Jim Reeves (‘The Blizzard’), Slim Whitman (‘Song of the Wilds’), Jeanette MacDonald (‘Indian Love Call’), Nelson Eddie (‘Rose Marie’), Kay Starr (‘Wheel of Fortune’), Faron Young (‘It’s a Great Life’), Joan Regan (‘Croco di Oro – Cross of Gold’), and Patsy Cline (‘I Fall to Pieces’).

With country songs, the sentiment and message are straightforward. The lyrics are about basic issues of life: love, heartache, death, jealousy, loneliness and joy. Country music gave the tough trawlerman an emotional outlet. Beneath his tough exterior, a gentle heart was beating!

Research shows that there might be other, deeper reasons why Hull trawlermen took to this genre of music. In essence, American country and western songs originated with the maypole music of Elizabethan England – which in turn dates back eons.

The peasant immigrants to North America from Britain took with them their traditional folk songs. Their songs passed from generation to generation, and the English Morris dance gradually transformed into square dances and country music.

Although it appears that the Hull trawlerlads latched on to a musical import from the United States, the argument can be made that the spirit of the music has remained unchanged, and it is that which has universal appeal amongst working people. In other words, the early American settlers were working country folk, and their music has returned home to Britain – albeit in a transformed genre.

I have very few pictures of Hull trawlermen playing musical instruments. But this rare one shows the crew of the Endon H 161 in 1932 with a banjo, accordion, mandolin, fiddle and flutes. I only wish I knew the repertoire of the group. It could easily have been country and western music in the 1930s.

In addition to the flamboyant suits, Hollywood movies, singing cowboys, western paperbacks and country and western music, there was one more significant area of the trawlermen’s lives that reflected their cowboy ethos – sport.

At the heart of the fishing community was the famous Boulevard sports ground where Hull Rugby Football Club played from 1895 to 2002. And loyal ‘Airlie Bird’ fans sang their battle hymn ‘Old Faithful’. Around 1933, this popular American song by Gene Autry, about a horse called Old Faithful, suddenly came into prominence and was adopted by the Hull FC fans.

Perhaps the key reason the supporters latched on to this song was that they had been brought up with cowboy music. It was easy for the fans to identify with being on a palomino riding the lonesome prairie. So it is natural that the Boulevard’s resounding anthem is – to this day – still a cowboy song, especially with its moving chorus: “Old Faithful, we’ll roam the range together, Old Faithful, in any kind of weather, When your round-up days are over, And the Boulevard’s white with clover, For you, Old Faithful, pal of mine.”

One of the attractions of being a trawlerman was the camaraderie between the crewmates. They spent three weeks cooped up together on a relatively small ship at sea and then, during their brief time ashore, drank together in the bars. In what other industry did this high degree of social interaction happen outside the workplace?

The Wild West lifestyle struck a chord with the young trawlerlads because there was a range of parallels between the two groups. Both struggled against the natural elements, encountered wide-open spaces, risked life and limb, and had a bad reputation for hard- drinking, boozy behaviour and pub/saloon fights. Relationships with women were often strained by long absences from home; there was an affinity between the cowboy and his horse and the trawlerman and his ship; and each was riding the range, or riding the waves.

Trawler cook Stan Cox made the point: “It was maybe because he was alone at sea – like a cowboy on the prairie being away from loved ones – the six-month cattle drive and the three weeks at sea.” There was a similarity between the two sets of men with their work and lifestyles.

The affinity between the Wild West cowboys and Hull’s Arctic trawlermen was embodied for all to see when they came ashore and walked around the city centre proudly wearing their ‘fishermen’s uniform’.

This story was taken from an issue of Fishing News. For more like this, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.50 here.

Sign up to Fishing News’ FREE e-newsletter here.