In the second part of his series on the ‘rule-beaters’, Phil Lockley investigates the effects of the ‘10m rule’ on wooden boatbuilding

History reveals that most vessels built from wood that were considered ‘rule-beaters’ were not actually made to beat the 10m rule – or indeed any rule. They might have been called ‘rule-beaters’, but they were vessels kept in proportion, and nothing like today’s giant 9.9m steel boats.

However, when the 10m rule was introduced, skippers who already owned wooden boats measuring just over 10m in length faced ruin if their boat was not brought under 10m. Those boats became true ‘rule-beaters’. Skippers were forced to sneak into the U10 sector – a courageous step into another ever-dwindling quota pool.

Valhalla, a wooden vessel that is pleasing to the eye, with superb lines and equally good seakeeping qualities. What a shame the authorities cannot see fishing boat regulations through the eyes of a boatbuilder.

On reflection, they admit that they jumped from the frying pan into the fire. However, as a short-term survival measure, becoming a rule-beater meant staying in the fishing industry rather than going bust.

Today’s favourite material from which to manufacture a rule-beater is steel; GRP comes a close second, particularly for building static-gear vessels. But these days, wood is not considered for any length of fishing boat. Wood has fallen out of favour with fishermen – a sad reflection of our modern world, because many old fishing boats made of wood are still hard at work.

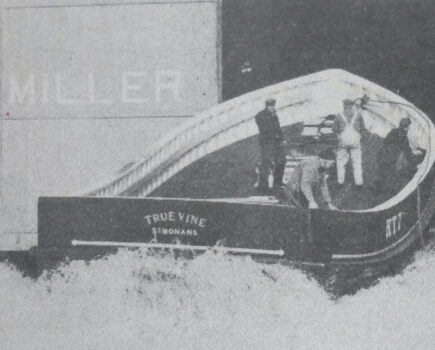

The Vervine – another example of a boat that ‘looks right’ and does not have its dimensions pushed to the extreme.

South West boatbuilders like C Toms & Son in Cornwall, Bobby Cann and his shipwrights from Brixham, John Leach and his son Peter at Mevagissey, and those at other yards who retain the ability to build a wooden fishing boat say that wood may be a cheaper material to use.

For hundreds of years, wooden boats underpinned fishing within British coastal waters. Even bigger distant-water boats were made of wood – beautiful boats, which the EU drove many of our fishermen to destroy.

Although wood is no longer a fisherman’s choice, in the high-priced market for new wooden yachts, a few small yards in Cornwall are thriving. Many boatyards in the UK can still maintain or repair wooden boats – skills that are being passed on to the younger generation.

Now a shelterdecked advanced netter working from Newlyn, this is the Britannia V just days after reaching its original home port of Mevagissey, after its completion at Nobles of Girvan in 1986.

I have seen wooden boats built at yards like John Moor & Son, C Toms & Son, Percy Mitchell & Son, G Pearn & Son, J Hinks & Son and Alexander Noble & Sons Ltd. Vessels that took my eye included the Julante, which once worked from St Mawes, and its sistership the Coquet Light, the Vervine, once working from Peel, and the Harvester, which worked from Flushing. Others included the 18.5m Valhalla, built by JW Miller & Sons at St Monans in 1985, and the Britannia V, built by Nobles of Girvan and now working from Newlyn.

Julante – a remarkable build and a superb sea boat – in the Flushing Trawler Race about 20 years ago. Behind are two other wooden vessels – Internos and behind it, Harvester.

In many of these wooden craft, the quality of build was so high that in my mind it was a shame to send them fishing. Every boat built by John Moor & Son holds that accolade. My favourite ‘Moor’s boat’ remains the Blejan Eyhre, probably the last built on traditional lines at the yard before modern styles came to dominate – as in the next Moor’s boat, Britannia IV. A similar traditional build was the Etoile, launched from Percy Mitchell & Son in the mid 1980s.

The Blejan Eyhre berthed at its home port of Mevagissey in 1984. Built at J Moor & Son and launched in 1978, it was the last fishing boat of traditional lines built at the yard.

When at C Toms & Son in Polruan recently, I spoke to its boss Alan Toms – who should be retired but is still seen at the yard many days. It’s a bit like asking a fisherman to stop fishing, I guess.

The history of C Toms & Son goes back to 1922 and Alan’s grandfather Charlie Toms, who developed the family firm with his son Jack – you can find out more at: ctomsandson.co.uk

Aurora, one of the few true rule-beaters built in wood by C Toms & Son, was launched in 1998.

It is difficult to calculate how many C Toms & Son boats I have reviewed in Fishing News. The first, I believe, was in late 1983. My archives include 916 pictures taken over the years at the yard, including over 30 new builds. Up to 20 years ago, many were made of wood, and sometimes the yard would have four or five wooden boats under build at the same time.

Over two-thirds of its workforce were once employed in building from wood. Alan Toms said: “The same applies to most yards – if wood came back for new construction, the men would soon be back with skills ready for new builds in wood. We carry out maintenance on many wooden boats – repairs, replanking, all sorts of things. New builds are no different, and we still have the old plans of our lines, and even patterns for the frames are still stored away.”

Alan Toms, head of C Toms & Son in Polruan, Cornwall.

I asked Alan how many true wooden ‘rule-beaters’ the yard had built. How many skippers wanted to beat the U10 rule, but in wood, and to cram as much as possible within the available constraints?

He said: “Up to a point, they were all rule-beaters, but they were ordered to be pretty boats, and in proportion – though many were only just under 10m in length. But in terms of a skipper asking us to build one, but make it as huge as possible – only one or two such boats were built.

A number of boatbuilders still have staff skilled in building wooden fishing boats. This picture was taken at C Toms & Son in the late 1980s.

“I suppose that the Aurora was built to give as much boat as possible. It is a Denis Swire design. Most fishermen think that designs from Denis Swire are only for steel boats, but in his early days Denis would regularly design builds in wood – very good boats, and never out of proportion.

“But with the Aurora, the measurements were stretched as much as possible – but it still looks in proportion, it still has traditional lines.

Maxine’s Pride on sea trials in 1985 – ‘one of the best-looking boats we ever built’, said Alan Toms.

“With boatbuilding in general, the call to make a small fishing boat as large as possible came when the 10m rule was changed from the registered length – measured from the rudder stock to the stem – to the overall length. Before that, we could easily put more boat from the rudder stock to the transom – but we never made those boats out of proportion, though some yards did.

Innisfallen was one of a number of 9.9m vessels built in wood at C Toms & Son – ‘built to be pretty boats, not rule-beaters’, said Alan Toms.

“But look at what we have today – those of 9.9m made in steel are massive. Even at yards like Macduff Shipyards, the under-10m boats are huge. In the past, both the owners and the builders wanted to make a pretty boat. I suppose that the new ones look OK, but never as pretty as those of the past. But that’s what the skippers want, and we can build whatever a skipper wants – as simple as that.”

Will wooden builds return?

Alan Toms said: “As a child, I remember one Saturday when St Ives fisherman Edwin Stevens came along to order a wooden boat of about 36ft in length. That must be over 50 years ago, at the start of regular demands for new builds of that size in wood. For years, the yard had built smaller mackerel boats and potters.

“Fishing was a good business to invest in. After the mackerel boom that began in the mid 1970s, fishermen did well and saw a good future in their industry.

George Edwin under construction at C Toms & Son.

“I was about 16 years of age, and saw orders placed for two more boats – like the one built for Edwin Stevens – boats of our design. One order came from a local firm as an oyster boat, and the other, a similar boat, to work from the Yealm near Plymouth. That was the start of me taking a serious interest in what was going on at the yard. From a very young age, I had no intention of being anything other than a boatbuilder.

Vessels like the Galwad Y Mor of Lymington were the result of growing demand for bigger wooden boats.

“Looking back to 40 years ago, we had an impressive order book on building mackerel boats, so many that it’s difficult to list them, but among the first skippers to order bigger boats specifically for handline fishing for mackerel were Newlyn skippers like Janner Thomas, Kenny Thomas, the Pascoe brothers, the Stevens family from St Ives – all of those skippers were very young and were making a lot of money catching mackerel, so they wanted to carry as much as possible.

“Further east at Polperro, Looe and Plymouth, skippers also placed orders. One of those boats is the 10m Tracy Claire, now working from the Helford as a netter. It is hard to think that originally it was built to carry tonnes of mackerel. All of those boats were to our design, and it was that demand that allowed my father to move the business to the present bigger yard at Polruan.

The wooden netter Sterennyk, only 30ft in overall length but equal to a traditional wooden rule-beater of 33ft.

“We must have built over 30 mackerel boats, from small to large, and other local yards were also building mackerel boats – Percy Mitchell & Son, John Moor’s yard, G Pearn & Son and several others – all were building from wood.

“After the mackerel boats, we went on to build the next generation of boats, boats aimed at different fisheries like netting. Skippers who had profited from the mackerel boom like Janner Thomas and Kenny Thomas ordered bigger boats like the Boy Gary and the Girl Pamela. Also working from Newlyn was Clive Hosking, who ordered the Boy Anthony, again a different style of boat. Styles were changing, boats were getting bigger, but skippers were not restricted by so many rules, so having boats over 10m in length was not a problem, but an advantage.

Yards like G Pearn & Son were also busy making wooden vessels. The Pearn yard had its own design – slightly thinner in the beam and with stylish lines – and they are excellent sea boats.

“Not long after, we built the Maxine’s Pride and other similar boats, with more advanced designs, and even fuller lines came with boats like Phil Trebilcock’s Guiding Light of Newquay, which later became a successful trawler at Looe.

“Skippers wanted bigger wooden boats. Yes, there was a demand for ‘big’ small boats of under 10m, but the fishing industry was profitable, so orders for boats like the crabber Galwad Y Mor of Lymington were also laid, and boats like the Trevas. It wasn’t a crime to have a bigger and better boat.

“Although the style was changing, original wooden builds of 9.9m in length – boats like the Kingfisher, the Innisfallen, the George Edwin and others – were far away from the present 9.9m steel boats, rule-beaters like the Saxon Spirit. Those wooden boats were in proportion, and most are still working successfully – so there is still a place for traditional wooden boats.

“Having just built the Boy Gary for Janner Thomas, I took it to Looe to tow back a yacht. On seeing it, a Looe fisherman said, ‘Look at that awful boat you’ve built, you’ve got a high bow on it, and look at its great big stern. You won’t build any more boats like that.’ But that had already become the new style – skippers wanted that type of boat.

“At that time, there was no limit on power, and skippers chose engines with sufficient power to cope with having a bigger transom. If they had been limited to a little Kelvin diesel like those that powered the much older traditional boats – smaller boats with leaner lines – they wouldn’t have been able to safely get their new boat out from a following sea. But that new style of boat gave them a very ‘big’ small boat.

“In general, the lines remained in proportion – boats like the Maxine’s Pride, a beautiful-looking boat, and the original Valhalla, that we built for Colin Warwick. In my mind, those are the best lines that ever left this yard.

“When it comes to beating the 10m rule, and going as big as possible in wood, the Aurora was built to beat the 10m OAL rule. It has a bulbous bow, and is a very deep boat, and much bigger than the others that we built at the time.

“Looking at how the lines have changed, one of the last wooden boats that we built was the Helford netter Sterennyk – only 30ft in length, but a modern style from Denis Swire, and a very big boat for its size, compared to many of our older 9.9m boats.

“We could largely copy the lines of today’s big boats – those built in steel – in wood, but in practice it would be uneconomical. But if a skipper wanted a giant 9.9m boat built in wood, we would build it for him.

“Sadly, I would be very surprised to see wood return as a building material for fishing boats. But whatever a skipper wants, we will make it for him; we still have the skills to build in wood.”

From the frying pan into the fire

Our Fiona Mary – an impressive gill-netter that once worked from Brixham – is an example of a wooden boat that was forced to become a rule-beater and shortened to bring its LOA below 10m; later renamed Fiona Mary, it was one of several South West wooden boats that were modified in such a way. This change was minor – some were brutal – but skippers had little choice.

In all cases, it wasn’t done to gain wealth from the U10 quota pool, but to avoid bankruptcy as a result of insufficient quota, whether working under the government management of the non-sector quota, or within a fish producer organisation (FPO).

Owned and skippered by Rob Penfold from Brixham, the Fiona Mary is a superb sea boat. A fisherman from a very young age, Rob largely stuck to fishing static gear.

Brixham is the centre of day-boat stern trawling and beam trawling, where netters are few, but Rob and a couple more inshore fishermen from Brixham ran successful netting businesses. Wreck-netting was Rob’s favourite, and I had the pleasure of spending two trips on his vessel – the first when it measured just over 10m, and the second when it had become a rule-beater.

I saw no difference in its seakeeping, but by the second trip, significant funds had been spent on a new wheelhouse, a new net hauler and much more. The Fiona Mary had become a more efficient boat – the exact opposite of what the authorities wanted the 10m rule to achieve.

The move, Rob explained, was a matter of financial survival. “The Fiona Mary measured just over 10m in length – she was a French-built boat with a counter stern – so all we had to do was have the upper part of the transom removed and replaced to squeeze under 10m in LOA. The principle was easy, but it was quite a big job for the shipwrights at Galmpton, near Brixham. At the same time, a new wheelhouse was fitted and considerable refit work was carried out.

“I didn’t want my boat to be changed, I didn’t want to go under 10m, and I don’t think any skipper in the same situation wanted to either. The term ‘rule-beater’ annoys me because I had no intention of beating any rule – just to stay within the rules to allow us to fish legally. But the authorities were changing the rules day by day, starving the smaller boats of quota. We were trying to adapt and make the best of a bad job, as simple as that.

“I had very little cod quota available from the FPO, but cod was a large part of my catch. I had moved from the Cornish FPO thinking it was better to be closer to home, but it wasn’t – the Cornish FPO had more netting boats, and was more suited to that type of fishing. Not long after being in the new FPO, I had insufficient quota for my crewmen and I to make a legal living.

“The desire to stay legal forced many skippers with boats of my size to go under 10m – either by converting their boats or by selling them to acquire an efficient rule-beater. Few, if any, would have bought a less efficient boat. The government was hellbent on getting rid of small boats, but it failed – and from what I see, it is still failing.

“Fortunately for me, at that time the price of an under-10m licence was relatively low – an over-10m licence was worth considerably more – so in effect, the refit on Fiona Mary cost me very little. I had enough money left for a new net hauler too. I invested every penny and a bit more back into my boat.

“When in the FPO, I tried leasing quota, but that wasn’t viable. I remember one trip when we had leased four tonnes of cod from an Irish FPO. We caught that fish quite quickly, but on landing we hit poor markets, the end result being that my crew, who each should have made about £1,600, ended up with just over £300. Profits from the trip had been wiped out by the leasing cost.

“At that point I decided that life for us, working within an FPO, was not sustainable. I was topping up the wages of my crewmen, and the boat’s share was dwindling. To stay legal within the FPO, we would have gone bust – no question about it.

“Four families were living off the Fiona Mary. Initially my boat did well as an U10, but it was not long before the future looked bleak. We tried whelk potting, tried hake netting, tried anything, really, to stay financially afloat and stay legal. But what we were good at – fishing for cod and pollack with wreck nets – became impossible. To this day, I know that those diminishing quotas, particularly for cod, had no true science behind them.”

Eventually, collapse of the cod quota for U10s would force Rob into his present job on offshore support vessels from Germany. “I’ve now been out of the fishing industry for eight years, but I regularly hear reports back from Brixham, and the netters there are still struggling – not with the ability to catch the fish, but with the availability of quotas. The cod quota is still dire.

“Who knows where the UK inshore fishing industry will end up after Brexit? To bring political calm, I think that DEFRA might ring-fence more quota for the U10s. But if they accept the same deal that we have now – effectively staying under the CFP – there will be an uproar across the UK, and not just from the fishing industry.

“Whether DEFRA and the MMO can regenerate the UK inshore sector, I’m not sure. Maybe they can, but the damage done so far is significant. In my mind, Brexit was the best thing that could have happened, but that’s looking long-term.

“Hopefully, any short-term pain will bring a long-term gain. I hope that small fishing businesses have a viable future after Brexit, and that Brexit is to everyone’s benefit – not just the vessels, but the small harbours and ports they support.”