Part 4 in the series A Trawlerman’s Reminiscences, written by Hull skipper William Oliver in 1953 (Photographs courtesy of Alec Gill)

In March 1905, we sailed again in the Cecil Rhodes for Iceland. We had a terrible trip for weather, and fishing was carried on only with very great difficulty. Gales of wind from, it seemed, every direction, with blizzards of snow, prevailed for days. At long last, we managed 1,000 kits with 400 kits of plaice, and we were fishing about 12 miles north of Adlevig one evening when the skipper called me on the bridge and asked me what I considered we had in.

We were all dog-tired, and eventually he decided to steam south as the wind was again freshening from westward. He instructed me to lash up the trawls, intending to complete his voyage at the Westmann Isles if the weather was suitable, and if not, to go home. I was told to set the watches and to turn in, as the skipper was remaining on the bridge for a time.

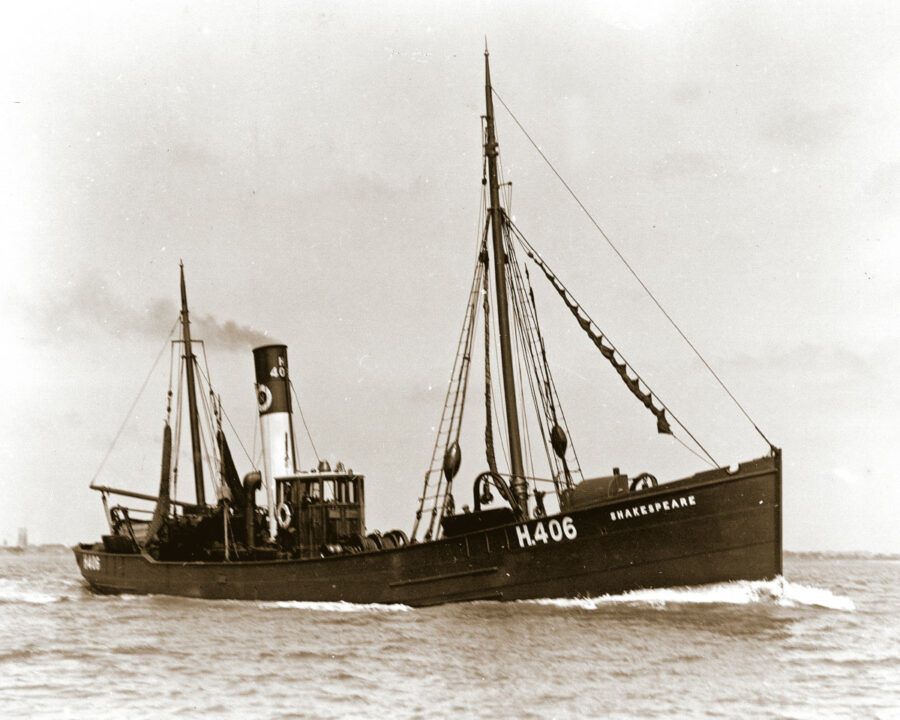

William Oliver sailed as mate in the Shakespeare in 1905, during the period the skipper of the Cecil Rhodes was serving a six-month suspension of his skipper’s certificate after the grounding of that vessel. That year saw the first landings from the Murmansk coast of Russia, popularly but wrongly called the ‘White Sea’ grounds. Shakespeare H 406 was lost in 1907 when she was at Breckness, near Stromness, Orkney.

Three hours after I turned in, at 1.15am on 4 April, I was awakened by a terrific crash, and when I went on deck I found that the Cecil Rhodes had steamed full speed ashore. Our poor old skipper had fallen asleep through sheer exhaustion, and I suspect the watch had done the same.

The ship had logged 30¼ miles, and when we measured it back to our point of departure, it made us on the corner of Onundas fjord. This proved to be the case. We launched the small boat and then tried the engines full speed astern, but the vessel refused to budge. She started to bump heavily, and after about two hours started to fill with water. We remained onboard until daybreak, and as the vessel showed signs of breaking up (we could see fish coming out of her bottom), the skipper reluctantly decided to abandon the ship and take to the boat. He and I were the last to leave. He was very distressed, and we all felt a great deal of sympathy for him. We learned later that had we arrived home safe, our voyage would probably have constituted a record, owing to the shortage of fish at Hull caused by the prolonged heavy gales.

We pulled up the fjord, and about noon we landed – a bedraggled-looking crowd at the settlement of Flateyre. We had some difficulty in making ourselves understood, but at last an Icelander arrived who could understand and speak English very well, and we were soon made very comfortable. We were really very fortunate, as that afternoon the wind increased to a heavy gale, and had our landing been delayed a few hours, we could all have been lost. At that time there were, of course, no telegraphic or telephonic communications with Iceland, so as yet, no news had been given of our disaster.

The way home

After we had been ashore for nine days, two trawlers arrived, seeking shelter from the bad weather, and seeing Cecil Rhodes stranded, came to the settlement for news of the crew. Half the crew, including myself, went onboard Pointer (Humber Steam Trawling Co), and the other half went onboard Peridot (Kingston SF Co), the skipper remaining onshore according to rule. We fished in Pointer for a few days, and then proceeded home, calling at Longhope in the Orkney Isles for coal.

Meanwhile at home, vessels were arriving and reporting heavy gales, and all trawlers were making long trips. Cecil Rhodes had been seen leaving the fishing grounds, presumably for home, and skippers had expressed surprise that she hadn’t arrived.

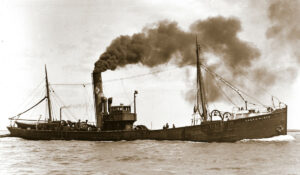

In 1906, William Oliver sailed as mate in a new-build vessel, Ocean Queen.

We had now been away over six weeks, and great concern was felt by our families, and tide after tide my wife was coming on the dock in anticipation of our arrival. One evening, my wire (sent from the Orkneys) arrived for my wife. It was the first news that Hull had of the loss of Cecil Rhodes. My wife took the wire to the owner’s house, and he was convinced of its authenticity.

I was required by the Board of Trade to give all the particulars in the absence of the skipper, who was still in Iceland, and was instructed not to sail until the Board of Trade inquiry. I received a subsistence allowance of £4 per week.

In due course the skipper arrived, and the Board of Trade inquiry lasted three days. The skipper was awarded six months’ suspension of his certificate, and I was free to look for a ship again.

He was very pleased with the evidence I gave, and it was arranged that I should be his mate when he was free to sail again. I filled in my time as mate of Shakespeare, owned by the now-defunct National Steam Trawling Co, running to Faroe, under skipper Henry Forrester, a Grimsby man sailing from Hull. I remained with him from June to December, when my old skipper’s period of suspension had ended. I left to go mate with him in a new vessel being built at Earle’s for his former owner, Mr J Hollingsworth.

That year, 1905, saw the first landings of vessels from the Murmansk coast fishing grounds (miscalled the White Sea), and I think the first two vessels were Sir Francis Drake (National SF Co) and Drax (Collisons).

Ocean Queen was owned by J Hollingsworth, steam trawler owner/manager and fish salesman.

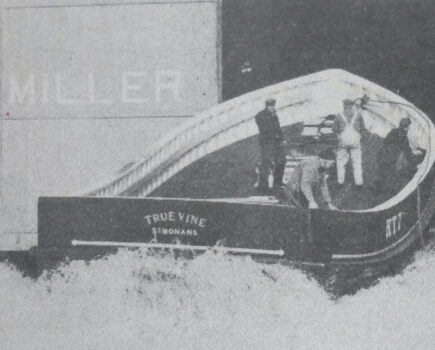

Drax was a new departure in trawler construction, being built with a whaleback on her forecastle head. Formerly all English trawlers were open-decked forrard, although a few German trawlers had whalebacks. This design was a distinct improvement, as when a vessel was steaming head to sea in open-decked ships, all the water rushed onboard in bad weather and the vessel had constantly to be stopped to clear herself. With the whaleback, when the vessel dived into the seas, the heavy water was diverted overboard again by means of a breakwater constructed on the after part of the whaleback. The next whaleback trawler was the Earl of Shaftesbury, and others followed in very quick succession. Trawlers were now constructed capable of carrying 2,000 kits, and had three furnaces in their boilers.

Our new vessel was the Ocean Queen, and we sailed on our maiden voyage on 3 January, 1906. We did very well in this vessel, landing some good voyages from the Westmann Isles, and later from North Cape. At the end of June, we stopped for what was then known as our six months survey – six months being the period when all defects were remedied before the builders finally turned the vessel over to the owners.

I go for promotion

As we were to remain in dock a few weeks, I decided to go to ‘school’ for my skipper’s certificate. I had been at ‘school’ just over a week when some vessels landed some good voyages from the Murmansk coast. Two of these vessels were Princess Victoria (Armitage’s ST Co), skipper P Hansen, and Golden Sceptre (Hall Leyman Co), skipper GW Leighton. It was decided that our ship, Ocean Queen, should be completed as soon as possible, so we could proceed to that area.

To my great disappointment, it was arranged for our ship to sail on the very Saturday at 9am that I was to sit for my certificate.

Golden Sceptre H 862 was wrecked in January 1912 when she ran aground at Kettleness on the Yorkshire coast.

I was very upset about it, as I did not want to stay ashore and miss the chance of going to the White Sea. I went to my skipper about it, who very kindly said, “Don’t worry, Bill, we’ll fix it.” And fix it he did. He explained the circumstances to the owner, and he was good enough to put a substitute onboard to leave the dock in Ocean Queen, when they would drop the anchor off the Victoria Pier until I had been examined. I had to give my word that I would proceed onboard immediately after my examination. I would say that such consideration is very rarely shown in our industry.

As the Ocean Queen was leaving St Andrew’s Dock, I was on my way to the Mercantile Marine Office to sit for my examination.

At 11.15am I came out of the boardroom with my blue paper, which denoted I was now qualified to act as a skipper of a fishing vessel of 25t and upwards.