Decommissioning in the 1990s and early 2000s led to the destruction of hundreds of seaworthy wooden boats – and a determined campaign to preserve a few for posterity

The Forbes-built Kimara FR 176, which was decommissioned in 2002 – just one of the hundreds of lost boats. (Photo: James Pottinger)

Reading the recent feature about the Happy Return and how she was saved from the chainsaw (Fishing News, 2 February, ‘Happy Return: Back from the brink’) took me back to 1994 and the start of the campaign to stop the enforced destruction of Britain’s fishing fleet.

I was in Peel on the west coast of the Isle of Man: it was the annual Peel Traditional Boat Festival, and I was there aboard my converted Loch Fyne skiff Perseverance, built in Campbeltown in 1912. I’d purchased her in Portugal in 1990 and had sailed her back to Scotland – where, in 1992, I’d celebrated her 80th birthday with the son and daughter of Archie Mathieson, who had commissioned her, along with dozens of surviving ring-net men who had known the boat during their working lives.

In Peel I met Mike Craine, whom many readers will remember well. He was a mine of information, especially on Manx boats, and the thing that drew us together was the decommissioning process currently underway, and the fact that the government was insisting that boats removed from the register were chopped up.

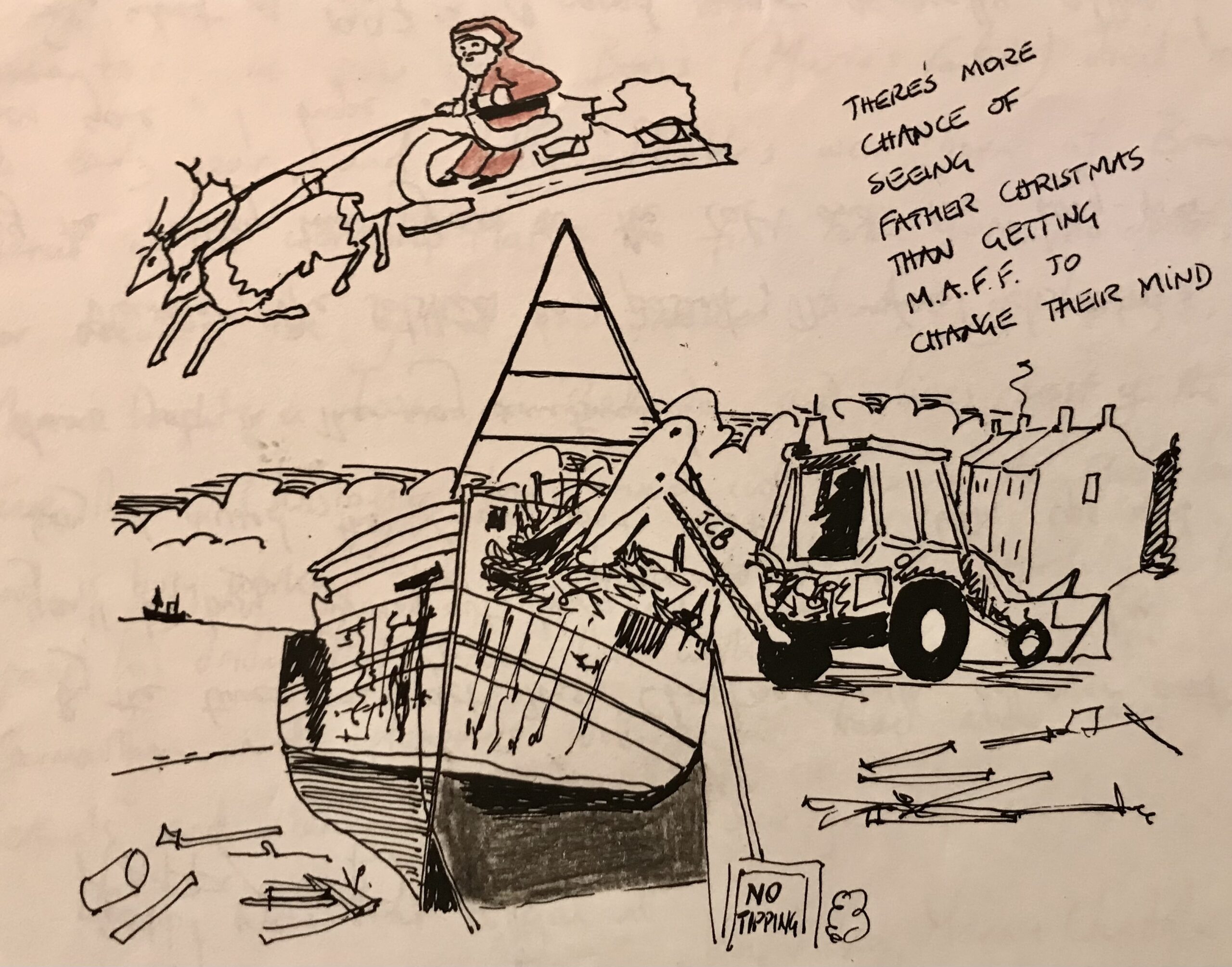

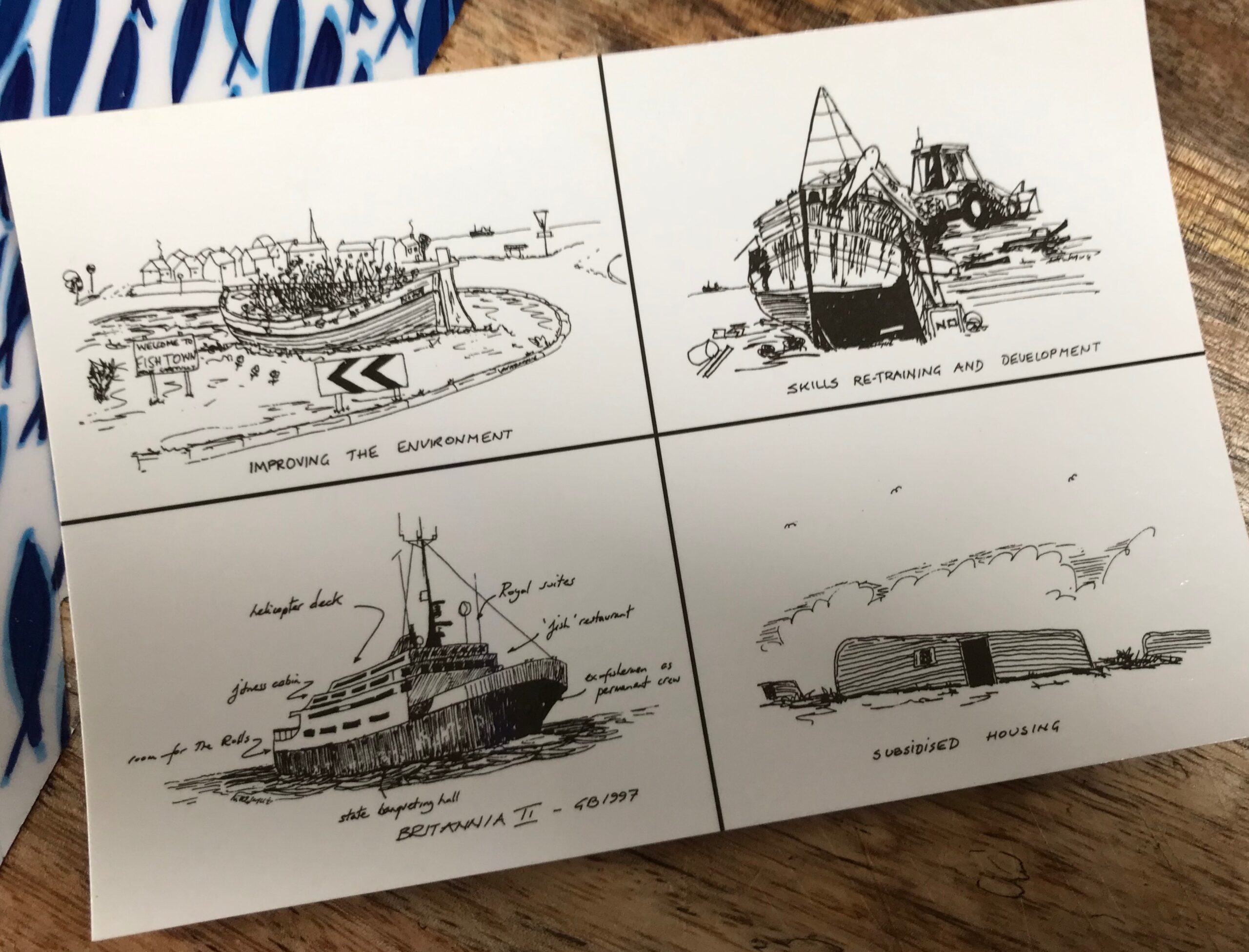

A Christmas card produced by the 40+ Fishing Boat Association.

So, as you do, we went to the pub to talk about it. A couple of hours later, we’d agreed to set up an association of boat owners to start a campaign to highlight the stupidity of such a policy, given that the vast majority of these boats were in perfectly healthy seagoing condition.

Thus the 40+ Fishing Boat Association was born – the ‘40+’ referring to boats over 40 years old, which generally excluded most steel and fibreglass vessels. It was never about the age of the owners, as some presumed at the time! (Or the founders, for that matter.)

By the spring of 1995 we were writing letters, and I’ve still got the files of replies, along with articles that were published about the campaign, including several in Fishing News. We weren’t against the principle of licence scrapping – that wasn’t in our remit – we were simply disgusted at the way boats were being treated. I’ve pictures of them being burnt, of one being pushed into Portland Quarry by a bulldozer, and many of JCBs chipping away at them with their back-actors.

More and less serious new uses proposed by the campaign for decommissioned boats.

Replies came from Tony Baldry, the Conservative minister in charge, and lots from opposition Labour members. There’s even one from a Mr Blair! One from Edwina Currie stands out: she rudely told us to go away because she was so busy with her many other commitments. She couldn’t even spell my name correctly.

Emma Bonino, the then European commissioner, sent perhaps the most encouraging letter – though, like all the others, it didn’t lead to anything much changing. Labour did commit to be prepared ‘to take a much more flexible view in terms of what happens to decommissioned fishing boats’ (letter from Elliot Morley dated 8 January, 1996). Yet Labour was in power within 18 months, and not much changed. Typical!

I remember going to Smith Square in London for an across-the-table meeting with various boffins from MAFF along with Dr Robert Prescott from the National Historic Ships Committee, the forerunner of today’s National Historic Ships, and Colin Allen, ex-captain of HMS Warrior.

A wooden boat being broken up – the fate of the overwhelming majority of decommissioned vessels during this period.

Over a couple of hours we worked our way through what we thought were reasonable requests but, increasingly, it became obvious to me that they didn’t care one iota. One of the fellows who seemed to be in overall control reckoned he was a tram buff, and attempted to liken saving old trams to saving old fishing vessels – except that trams weren’t being decommissioned, their owners weren’t being paid to surrender their licences, and trams weren’t being bulldozed in disused quarries! Furthermore, museums liked old trams because they were colourful and generally static.

Although I emerged from that meeting feeling that they were simply going through the motions, there was a speck of light at the end of the tunnel. This came from a proposal from Robert Prescott, who sounded out the possibility of museums taking over ownership of decommissioned vessels. A seed was planted.

Tyroca FH 476 being dismantled. (Photo: Billy Stevenson)

We agreed that it was movement, although we couldn’t really see museums wanting the responsibility of looking after the boats, even if a ‘caretaker’ was found. This was enforced by a headline I saw: ‘Fishing museums must not become a boat hire business’.

Oh, there were the funny bits. One of our ideas for publicity was when the government was contemplating building a new royal yacht. We had some laughs designing one from an ex-trawler, and sent the plans to Prince Charles.

Another time, we suggested various tongue-in-cheek uses of old boats: turned upside down as storage sheds, or installed as features on roundabouts. I’ve still got the postcards we had made up of the latter!

Dundee dry dock in around 1996. (Photo: Rudiger Bahr)

But in addition to the Britannia/Happy Return, only two other vessels escaped: Peter Blamey’s Lindy Lou FY 382, from Mevagissey, and another I can’t remember the name of. And of those three, only the Happy Return came to anything permanent. Lindy Lou currently languishes on a beach near Truro.

One report suggested a dozen vessels were saved, but there’s no evidence of that number staying at sea. Being plonked ashore, such as the Confide PZ 741 at Land’s End, as a static exhibit, doesn’t really count as ‘saving for posterity’. A few others were preserved as museum displays, or converted to uses such as fishermen’s stores.

Several examples can be seen gradually rotting away in harbours around the coast – which helps to makes sense of the old fishermen’s way of sinking their boats as they neared the end of their working lives. I know of the resting places of several Loch Fyne skiffs in the waters around the Scottish west coast.

Try Yann PZ 7 being broken up at Newlyn in 1996.

But the overriding outcome of this really pointless government exercise was the list of boats that have disappeared. As I continue writing the history of the four boatbuilders in Fraserburgh, the phrase ‘decommissioned in…’ recurs all too often. Hundreds of perfectly seaworthy wooden vessels were simply consigned to the scrap heap by the intransigence of policy-makers. Many more hundreds, when you look round Europe.

I spent hours watching one boat being pulled apart in Newlyn – the 1875 French built Try Yann. The JCB kept jabbing at it, splintering shards of wood away with ear-splitting cries. The boat did not want to give up. Hundreds of hours of superb workmanship, and many decades of strong growth in the oak and larch, went into creating the vessel, and that JCB seemed no match by comparison – although, of course, in time it won.

I felt mixed emotions: anger at the policy, sadness at the destruction, and a pride that the boat was fighting back.

Without our efforts and those of a handful of others, Grimsby Fishing Heritage Centre would never have been able to jump through the hoops that allowed it to secure the future of the Happy Return.

But hundreds of other UK boats – no one knows the exact number – were legally vandalised. Only one boat remains at sea as an epitaph to all those gone. Long may she continue to sail.

This story was taken from the archives of Fishing News. For more up-to-date and in-depth reports on the UK and Irish commercial fishing sector, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.30 here.

Sign up to Fishing News’ FREE e-newsletter here.