With the first Scottish pelagic vessels starting to fish North Sea mackerel southeast of Shetland last week, David Linkie looks back to a trip on the Peterhead midwater vessel Lunar Bow PD 265 in the second week of October 2014

In 2011, after a nine-year period from 2002 during which the Scottish pelagic fleet had fished exclusively with midwater trawls, two Peterhead vessels, Lunar Bow and Pathway – both of which were built with pursing capability during that period – shot their purse nets for the first time during the autumn mackerel fishery in the North Sea, where pursuing continued to be the main catching method favoured by Danish and Norwegian mackerel boats.

01. Lunar Bow hauling the purse net north of Out Skerries.

02. The Shetland Coastguard rescue helicopter leaves Kings Cross on completion of a routine training exercise.

03. Lunar Bow searching close in to Bressay.

04. Away she goes – David Ritchie and Zander Strachan drop the dahn.

05. Running the purse net off for the first shot of the trip.

06. Lunar Bow’s crew stack the purse in the net bin.

07. A blank haul off Noss.

08. The Whalsay midwater trawler Research searching south of Noss.

09. Hauling what proved to be a badly torn purse net in tranquil early-evening conditions.

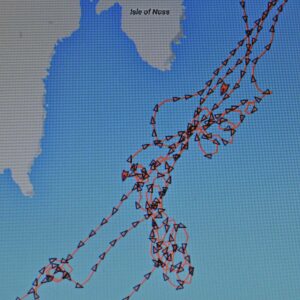

10. Lunar Bow’s tracks as shown on AIS during an eight-hour period in which the purse net was shot twice.

11. Hauling the damaged purse onto the quarter.

12. The crew of Lunar Bow start to pull out the first of the torn sections.

13. Alex Pirie and the troops lacing up smaller tears.

14. Dave McLean guides the purse down into the net bin from the net stacker.

15. 100t of mackerel from a successfully repaired purse net was a welcome sight on Tuesday morning.

16. Taking the purse through the Tristar hauler.

17. The Whalsay and Fraserburgh midwater trawlers Charisma and Chris Andra towing to the north of Out Skerries.

18. Zephyr towing.

19. Pathway searching down the back side off Lunar Bow’s purse net north of Skerries.

20. Tracking a good mark.

21. Fish start to come off the bottom and shoal up as darkening comes into the water.

Although they revert to single-boat midwater trawling when fishing mackerel, blue whiting and herring in the first nine months of the year, Lunar Bow and Pathway continue to purse for a few weeks each year at the beginning of the autumn mackerel fishery.

Dawn on a fine quiet morning in October 2014 saw Lunar Bow steaming at 14.5 knots on a heading of 9° three miles east of Fair Isle, seven hours after leaving Fraserburgh harbour.

Severe southeasterly gales of up to 50 knots at the beginning of the previous week had resulted in Lunar Bow successfully purse-netting to the west of Shetland between Eshaness and Papa Stour.

This represented a considerable change from the opening weeks of the season – which for the first Scottish vessel away had started in mid-September – when due to the autumn mackerel migration southwards to the Shetland waters taking a lot longer than anticipated, Lunar Bow and Pathway initially pursed more than 300 miles north of Peterhead in international waters alongside a large fleet of Norwegian purse-net vessels.

As a result of Pathway having found good marks inside the 12-mile line east of Bressay when conditions improved at the end of the previous week, Lunar Bow’s skipper Alex Buchan was expecting to start searching in a similar area this trip.

This thinking was reinforced over the weekend when a number of midwater trawlers from Shetland and northeast Scotland took good hauls of larger mackerel (400g-plus) along the shore less than 10 miles from Lerwick harbour between Bressay Bard and Mousa.

With Lunar Bow’s radar showing five midwater trawlers – Havilah, Ocean Venture, Research, Unity and Voyager – either searching or towing in this area, Lunar Bow started looking for marks a couple of miles north of Sumburgh Head.

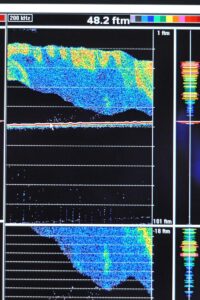

While the Kaijo KCH 2180 and KCS 3220 high-frequency sonars were soon displaying mackerel at a range of over 800m, neither the marks nor the bumpy bottom in relatively shallow water were considered worth shooting on in bright conditions, when the fish were expected to be extremely flighty.

Two hours later, the sound of the regular sonar pings was interrupted by the pilot of the Shetland Coastguard rescue helicopter requesting permission from the skipper of the Peterhead midwater trawler Kings Cross to land the winchman on the quarter as part of a routine training exercise.

Although Kings Cross had just picked up a promising mark, a few minutes after the Fraserburgh-based Ocean Venture had shot close by, the go-ahead was immediately given as Kings Cross kept a constant heading – away from the fish. After the rescue helicopter returned to pick up the winchman to complete a successful operation, Kings Cross picked up the mark again and headed west in preparation for shooting away the midwater trawl and towing into the eastward for 400t.

With bright conditions resulting in the mackerel spreading out, Lunar Bow searched south of Bressay and the adjoining small island of Noss until noon before the standby call led to the crew quickly gathering in the changing area to put on their deck gear. After tracking the selected mark for 30 minutes to determine its rather erratic direction, the shout of ‘away the dahn’ immediately resulted in David Ritchie and Zander Strachan dropping the drogue into Lunar Bow’s wake. As the drag of the sea anchor gained momentum, the bunt end of the purse net, which was 441 fathoms long and 119 fathoms deep, started to be pulled clear of the net bin.

The first four sections of netting in the wedge end of the purse, the taper of which is cut on two bars/three meshes, are made from 140mm mesh and no. 32 twine. Representing a considerable increase on the size of mesh used in the first sections of a purse net 20 years ago, the bigger meshes offer less resistance in the water when the more powerful class of vessel is thrusting away from the net, and so helps to reduce the risk of damaged netting.

A six-bar/one-side mesh is used on the taper of the bag section, which is made from 33mm mesh netting and no. 32 twine. The thinnest twine, no. 10, is used in the 216m-long main section of the net, which is constructed from 39mm mesh netting. Heavy-duty 20mm mesh guard strips are fitted along the heavily leaded footrope to help minimise damage should the purse net come in contact with the bottom, above which there is a 1½-fathom section of bigger mesh tearing strips.

Three thousand G-12-T corks are used on the headline of the net, which is 752m in length and constructed from double 30mm-diameter terylene four-strand rope.

Lunar Bow’s purse winch was spooled with 1,300m of 30mm Bridon Dyform wire, of which 1,100m were usually shot, along with either 225m or 275m of the 400m of wire carried on the dahn winch.

With the net running cleanly out of the purse bin through the elongated opening on the starboard side underneath the boat deck, the 53 purse rings were rapidly pulled off the shooting needle onto the purse wire by the five-fathom footrope strops. With a short dahn (225m) called for, the winch brakes were applied as the halfway marker on the headline hit the water, before the dahn wire started to be hauled back through a hanging block on the forward gallows.

Within 20 minutes of shooting away, the large meshes of the wedge end were hauled back to the Karm Tristar 24t hauler, before passing upwards into the net tube and over the net stacker and then leading down to the net bin, where eight crewmen were waiting to start flaking down the net.

Not entirely unexpectedly, the first purse did not produce any fish, so after a couple of small tears – tagged with markers prior to passing through the Tristar before being pulled clear of the net bin – were quickly laced up, Lunar Bow resumed searching for marks.

After moving east of Noss – where Lunar Bow passed Chris Andra, returning from landing in Norway, and the Whalsay boats Adenia and Research, which had just started fishing that morning – skipper Alex Buchan continued to search for the next three hours in a southwesterly direction across the south entrance to Lerwick harbour five miles away.

Perils of purse-seining

Shortly before 4pm, a potential mark was located in 38 fathoms of water, but with the water depth of immediate concern and the behaviour of the fish again proving difficult to establish, Lunar Bow spent the next hour repeatedly circling the mark, while the crew stood at their allotted workstations on deck, ready for the shout to drop the dahn.

Shooting 30t of purse net at over eight knots on a one-way trip in just 15 minutes is probably among the most intense periods of fishing activity, due to the number of variables that need to come together for a successful outcome.

Although purse-netting can be rewarding, it is an extremely intensive fishery for skippers and crewmen, as well as being physically demanding. While good hauls can be alongside in less than two hours, extensive gear repairs are a constant characteristic of pursing, particularly when fishing in shallow water.

With a short dahn again being called, the purse net was eventually shot in 39 fathoms, with the winch being braked when the quarter headline marker hit the water, as hauling back started with half the purse net still in the bin. Unfortunately, by the time just over half the net was aboard on a beautiful tranquil evening, it was obvious that the best efforts of a highly experienced purse-net skipper and crew had not been sufficient to avoid extensive damage, as the first of a series of ragged tongues of loose netting extending the full depth of the net across five panels began to be taken onboard.

As soon as the bunt was aboard, the crew started to run the net back through the block and flake it down on the central trawl deck. By the time the headline corks were level with the boat deck, the first of the torn sections were pulled across to port, as the crew tried to determine the extent of the damage, and whether repairs could be carried out at sea.

Over a quiet supper of chili con carne, quickly prepared by cook for the week Gordon Pirie, the initial prognosis was: “It might just be possible, but as the damage is bad and over a large area, it is too early to tell.”

With each crewman lacing up to 10 fathoms of netting an hour, the benefit of over 200 years’ combined experience of pursing, in which large-scale repairs are an accepted part of the job, eventually prevailed. After 14 hours on deck, during which the crew laced around 1,600 fathoms of netting, the purse rings were back on the shooting needle and the net was neatly flaked in the purse bin, awaiting the call to stand by when it came.

Good to go again

Shortly after giving the crew time to appreciate the well-deserved breakfast rolls, the dahn was dropped in 68 fathoms just inside the 12-mile line east of Bressay, where the skipper of the Danish vessel Isafold was reporting shooting on a good mark two miles further east.

Although Lunar Bow had tracked a reasonable mark, the main priority was to confirm that the net had been put back together correctly and was fishing fair. Confirmation of this gradually became evident during a smooth haul, which towards the end started to show some welcome signs of mackerel. Lowering the fish pump resulted in around 100t of good-sized fish (390g) flowing down the delivery chutes into the selected RSW tanks. The bigger bonus, however, was that all seemed well with the net.

Reports from UK skippers of generally smaller hauls as daylight strengthened saw the skippers of four Whalsay boats, Adenia, Charisma, Research and Zephyr, use their extensive knowledge of the local grounds to move 15 miles north to a new area between Out Skerries and Yell, where two Fraserburgh midwater trawlers, Forever Grateful and Sunbeam, were reporting a wide spread of good marks.

One hour later, during which time the Fraserburgh boat Resolute also returned to the grounds after landing in Egersund, Lunar Bow rounded Out Skerries lighthouse as skipper Alex Buchan started to look for suitable marks in an extensive bay flanked to the west and north by the islands of Yell and Fetlar.

While some trawlers were pumping mackerel onboard after successfully towing around four miles off the shore, others were marking fish closer in before turning to shoot and tow out.

The combination of bright sunlight in relatively shallow water meant that conditions were not particularly favourable for purse-netting, with fish widely dispersed throughout the water column. After searching for three hours inside of where most of the trawlers were fishing, a slightly more encouraging mark resulted in Lunar Bow’s crew being called on deck again.

Thirty minutes later, the purse net was running out of the bin ahead of a swiftly moving mark. By now, Lunar Bow had been joined on the grounds by her purse-seining counterpart Pathway, whose skipper reported no signs of fish in the net as he passed down the back of the headline. Not entirely unexpectedly, this observation proved accurate 40 minutes later on completion of hauling, when the purse was readied for the next shot without seeing a tail.

Unlike most other methods of fishing, when even a poor haul usually results in some fish being caught, complete blanks, reflecting the often flighty nature of mackerel (and herring), are a common characteristic of purse-seining. Given the considerable number of variables involved – including depth of water, changing underwater currents, and the depth, speed and direction of movement of the fish, allied to their ability to change direction at the last minute to swim either under or outside the net – this is understandable.

However good modern acoustic technology is, at the end of the day the outcome of pursing is determined by the experience and skill of the skipper in determining just how far ahead of the mark and in what direction to shoot, and then when to start pursing – when a highly experienced crew makes an equally important contribution.

Searching resumed immediately, with Lunar Bow moving northwards towards Fetlar before following an approximately reciprocal course, paralleled most of the time by Pathway less than half a mile distant.

During this time, Altaire arrived in the area from the west side of Shetland via Yell Sound, while Quantas returned from Norway. This meant that half of the Scottish pelagic fleet of 22 boats were fishing within 10 miles of each other. This fine sight provided a timely reminder of the value of the western mackerel stock, and the crucial importance of promoting the long-term sustainability of extremely healthy stock levels.

Experience and perseverance deliver

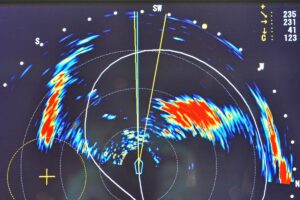

As Lunar Bow continued to search a couple of miles northwest of Skerries light, the sonar and sounder displays made it ever more apparent that there was an abundance of fish in the area – observations that were echoed by Pathway skipper Georgie Buchan half a mile away to the northwest.

Although the fish were tight to the bottom in 45 fathoms of water, the minimum required for safe pursing, one mark in particular attracted skipper Alex Buchan’s attention as he started to slowly circle the mark to determine its size, shape and movement.

With daylight fading, the fish were expected to lift off the bottom as darkening came into the water. Over the next 60 minutes, this prediction proved correct, as Lunar Bow continued to slowly circle a mark over 1,000m in length and 400m wide, and more than 20 fathoms deep.

Anxious about the non-existent margin of clearance from the leadline to the bottom, and looking to take the edge of the mark only in order to reduce the risk of a big haul possibly damaging the net, Alex Buchan weighed up his options before the dahn was dropped as the last vestiges of daylight disappeared over mainland Shetland three miles to the westward.

As the mark continued to move slowly into the northwest, Lunar Bow’s purse net was shot up the side and across the front of the mark.

Shortly after hauling commenced, Pathway came down the back side of the net before starting to shoot on an equally good mark.

Towards the end of what proved to be an uneventful haul, a few small pockets of trapped mackerel fell back into the net as the remaining circumference of the headline reduced rapidly, providing the first indications of a successful purse. This was soon confirmed by increasing numbers of diving gannets, before surfacing pursed mackerel brought the sea alive off Lunar Bow’s starboard side, 75 minutes after the dahn had been shot away.

Although an impressive sight when jumping out of the water in frenzy as the bag was dried up, only a small proportion of the mackerel netted were evident on the surface. This was still sufficient to indicate a good haul, estimated to be over 500t.

With the bunt having come alongside fine and square, as a result of which the raised corkline was quickly secured well clear of the water, the crew came forward from their previous workstations in the net bin in preparation for pumping to begin.

Pursing nets live catches, so within a few minutes of the 18in Karm fish pump being lowered over the side, still-flapping mackerel started to cascade down the delivery chutes towards the aft RSW tanks. In order to maintain the fish in prime condition, the aft tiers of Lunar Bow’s 12 storage tanks were filled with some 600t of seawater, already chilled down to -2°C, to ensure that the catch would be quickly cooled to the optimum temperature. To ensure maximum fish quality, the mackerel would be kept in a 50/50 ratio with chilled seawater, which engineer Michael Willox would circulate into the forward tanks as pumping progressed, before ensuring that a temperature of -2°C was maintained until landing.

The extent to which purse-seining delivers prime-quality live fish, subsequently maintained by modern pumping and catch storage equipment, was shown by the fact that two hours after coming aboard, mackerel were still swimming in Lunar Bow’s RSW tanks.

Some of the first mackerel to pass through the MMC water separator were quickly scooped into a basket and passed down to Alex Pirie in the pumping control room to be individually weighed on the Marel electronic scales. The readouts, transmitted automatically to the wheelhouse, subsequently gave counts over 10 samples of between 385g and 420g, to give a good overall average fish size of 400g.

Hauling less than one mile to starboard, Pathway skipper Georgie Buchan reported taking a possibly bigger haul – the downside of which was that with the net leading further aft than usual, the weight of fish had pulled the corks down, allowing an estimated half of the catch to swim for freedom over the headline, although 450t were still pumped aboard.

While Lunar Bow was pumping and therefore lying stopped in the water, further evidence of the quantity of mackerel close into the shoreline of Shetland was unexpectedly provided by the Simrad ES-60 sounders, which started to display a huge mark of fish extending from just a few feet below the hull transducers down to the bottom in 42 fathoms.

Two hours later, Pathway took 600t of mackerel from this mark by managing to successfully skim the edge of it.

As pumping continued on Lunar Bow over the next 90 minutes, the number of RSW tanks brought into use steadily rose until 800t of mackerel had been pumped aboard. Not surprisingly, the mood around the mess table at supper an hour later, as Lunar Bow started to steam 180 miles back to Peterhead, was considerably more upbeat than it had been 24 hours earlier.

Immediately on berthing at Peterhead at lunchtime the following day, the fish landing hose was quickly connected to the quayside pipe before the first mackerel were discharged ashore, less than 18 hours after leaving the sea.

With catch quality of paramount importance in a fiercely competitive global marketplace, the fat content of Lunar Bow’s mackerel was regularly sampled and recorded, while the whole fish were graded, boxed and frozen in line with the requirements of international end buyers.

Fleet renewal

Observing midwater trawlers like Adenia, Altaire, Charisma, Chris Andra, Forever Grateful, Research, Resolute, Sunbeam and Zephyr fishing in close proximity to Lunar Bow served to illustrate that although these and other similar vessels clearly represented significant private reinvestment in the pelagic sector, the Scottish midwater fleet had seen no new arrivals since 2008.

This situation was a stark contrast to that in Norway and Denmark, where pelagic operators had taken delivery of a succession of new vessels representing the next generation of considerably bigger midwater boats.

Given the international nature of modern pelagic fisheries, when Scottish vessels regularly fish alongside boats from other countries bordering the North Sea and beyond, the importance of being able to continue to compete on a level playing field by investing in new efficient vessels landing prime-quality fish was crystal clear.

Acutely aware of the need to replace ageing vessels, owners began to take the decision to replace existing boats. The first of the new builds, Kings Cross and Antares, entered service in 2016. The following year, they were joined by Pathway, Grateful and Voyager. Ocean Star, Serene and Research started fishing in 2018, while Taits, Adenia, Zephyr and Charisma were delivered in 2019. A new Lunar Bow crossed the North Sea from Skagen at the start of this year, which is also expected to see the new Resolute arrive from Spain.

The arrival of these 14 new midwater vessels highlights the healthy state of pelagic stocks in UK waters, as well as the ongoing commitment of all the shareholders involved.