With the appointment of a new Admiral of the Manx Herring Fleet to celebrate the landmark reopening of the Isle of Man herring fishery, FN looks back at its history and traditions

By Mike Smylie

Herring – Y Skeddan in Manx – is the king of the sea: ree ny marrey. This fish, like no other, features in Manx household sayings of old, such as gyn skeddan, gyn bannish (no herring, no wedding) and palchey phuddase as skeddan dy liooar (plenty of potatoes and enough herring).

Herring was the Manx national diet, as it was throughout Scotland and Ireland, and parts of Wales and England. So you’d be forgiven for thinking that early fishermen never caught anything else. But that, of course, is not correct.

Of course our early fishermen landed other fish. However, herring was the first true ‘fishery of consequence’, as against just landing a multitudinous supply of whatever came into the net, or onto the hook. That was great for the Isle of Man, centred nicely in the sea of which the herring was king.

Not only that, but a superior herring migrated into the Irish Sea, similar to that of Loch Fyne. Herring spawn off the Manx coast, especially liking the coral seabed on the Douglas Banks southeast of the island, although rich grounds were also found on the opposite side and in the deeper water between the island and the Irish coast, some 30-odd nautical miles away to the west-northwest.

It is said that it was the Scots who taught the Manx to fish, probably during their rule of the island in the 13th century. Thomas, bishop of Sodor, was the first to mention ‘the strangers in the herring fishery’, with regard to taxes paid by these fishers – which assumes a fishery attracting outsiders. That was in the first half of the 14th century.

What is perhaps more interesting from the point of view of today is the way the fishery was run. It was almost like a military operation, with the fishermen being controlled by water bailiffs and Admirals of the Herring Fleet.

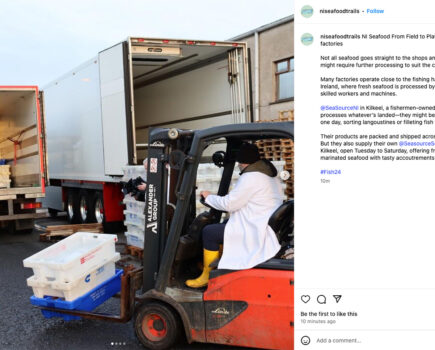

The smaller Manx nobby type.

This tradition is said to have come from the days of the Norse kings. Indeed, the 1610 Manx Statue Book includes a long list of regulations showing that fishermen were under tight discipline, and had been for some time. That fishermen were only seasonal is attested by the requirement for the more substantial, or ‘quarter-land’, farmers to provide eight fathoms of nets fitted with corks and buoys in readiness for the fishing.

The start date of fishing was decided by regulation, and the masters of boats had to muster their vessels at the prescribed place at the requisite time. Failure to do so brought the onslaught of the state down on them!

The vessels they used for the herring fishing came from the Viking age. Called scowtes, these were single-masted, square-sailed vessels used specifically to chase the herring shoals. They were variants on the Icelandic skuta, which were fast vessels carrying sails and oars.

Like the generic Viking longship, these had considerable sheer forward, with curved stems and sternposts, and were open craft. The length of their keels – the normal way of measuring craft in days gone by – was between 20ft and 24ft, giving them an overall length of up to 28ft. They were clinker-built (planks overlapping instead of edge-to as in ‘carvel’).

It was the Admiral of the Herring Fleet who reported to the water bailiff any misdemeanours at sea such as shooting nets at the wrong time or cutting across someone else’s nets, which would then be dealt with at the next court session.

There was a vice admiral as well, and both were appointed by the water bailiff. They were taken on for the duration of the fishing season and, in 1798, were paid £5 and £2 respectively by the government. The admiral and vice admiral had distinguishing flags on their boats.

The Manx nobby Gladys PL 61, built in Peel in 1901 and still sailing today out of Falmouth – though no longer at the fishing!

Nets could only be shot at night, so they lowered their flag to show when shooting could commence, raising it at dawn.

And don’t think about not turning out to fish. In July 1705, the skippers of some 14 boats from Kirk Bride were hauled before the court after being charged to go to the herring fishing at Port Erin and ‘to have their nets and buoys and other things pertaining to the said fishing in good order’. The inference is that they failed to turn up or their gear wasn’t up to scratch!

Up to 1765, when the British crown took control over the island, goods were brought in after paying a very low import duty. This allowed a flow of ‘free trade’ towards the four adjacent countries – which from the crown’s point of view was smuggling.

It was a lucrative trade, and many fishermen with access to boats benefited from the island being the central storehouse. But during the fishing season, the herring always took precedence.

Other regulations regarding the duties of fishermen are fascinating. When finding a shoal of herring, the crew of that boat was required to pass this information to the nearest boat, which would then pass the message to the next; in this way, the information was transmitted to the whole fleet. Imagine that today!

The Manx Belle PL 62, one of several ‘Manx’ boats built with Isle of Man government funding to expand the herring fishery in the late 1930s and early 1940s. There were nine in total, the Manx Belle being built by Tyrrells of Arklow in 1943.

Another law of 1737 states that herring cannot be exported until the island’s people are fully supplied at a price not exceeding 1s 2d per hundred. In lean years, herring was imported to satisfy local demand.

In the late 18th century, it is said that there were up to 400 boats sailing ‘in and out of Douglas every day’, which shows that the east coast fishery was centred in the port. Every weekday, most of them set out before sunset when the weather was fair, ready to cast their nets as the sun dipped below the horizon.

The fishermen adapted the smack rig on their basic boats until the Cornish fishermen arrived in 1823 and, finding fishing so successful, began to return year after year. The Cornishmen came in their powerful drivers – lug-rigged with two masts. They tended to ride to their drift-nets with the mainmast lowered and only the mizzen sail set. The Manxmen saw the advantage, and quickly adapted their own vessels by shortening the main boom and stepping a jigger mizzen mast to convert to a dandy rig of gaff mainsail and lug mizzen. They also stepped the mainmast in a tabernacle so they, too, could lower it when lying to their nets. These became known as Manx luggers, and between 1840 and 1860 almost the entire fleet was thus rigged.

In 1848, the price of a 40ft Manx lugger was around £155. However, as boatbuilding techniques improved, sizes increased to around 55ft, and the largest were entirely decked over.

By the 1860s, the Cornish had perfected their luggers and were visiting the island in some number. The Manxmen, instead of building dandy-rigged craft, began to copy the Cornish boats in hull shape and rig. Because many Cornish fishermen were named Nicholas, so it is said, they termed their new boats nickeys!

At first they bought in vessels from the well-known builder William Paynter of St Ives, but soon the first home-built nickey came from William Qualtrough of Port St Mary in 1869. This was the Alpha, and many more soon followed. The hulls of the nickeys were between 50ft and 60ft. They had accommodation aft of the amidships fish hold, berths for eight crew and a stove. Forward of the fish hold was the net room and bosun’s locker.

The Port St Mary fleet beached: again the same two-masted nickeys.

When sailing to the Kinsale mackerel fishing in March, they would commonly make the passage in 48 hours – a fast time even by today’s standards. By 1881, there were 334 Manx boats taking part in the herring fishing, the largest number being registered in Peel and Castletown.

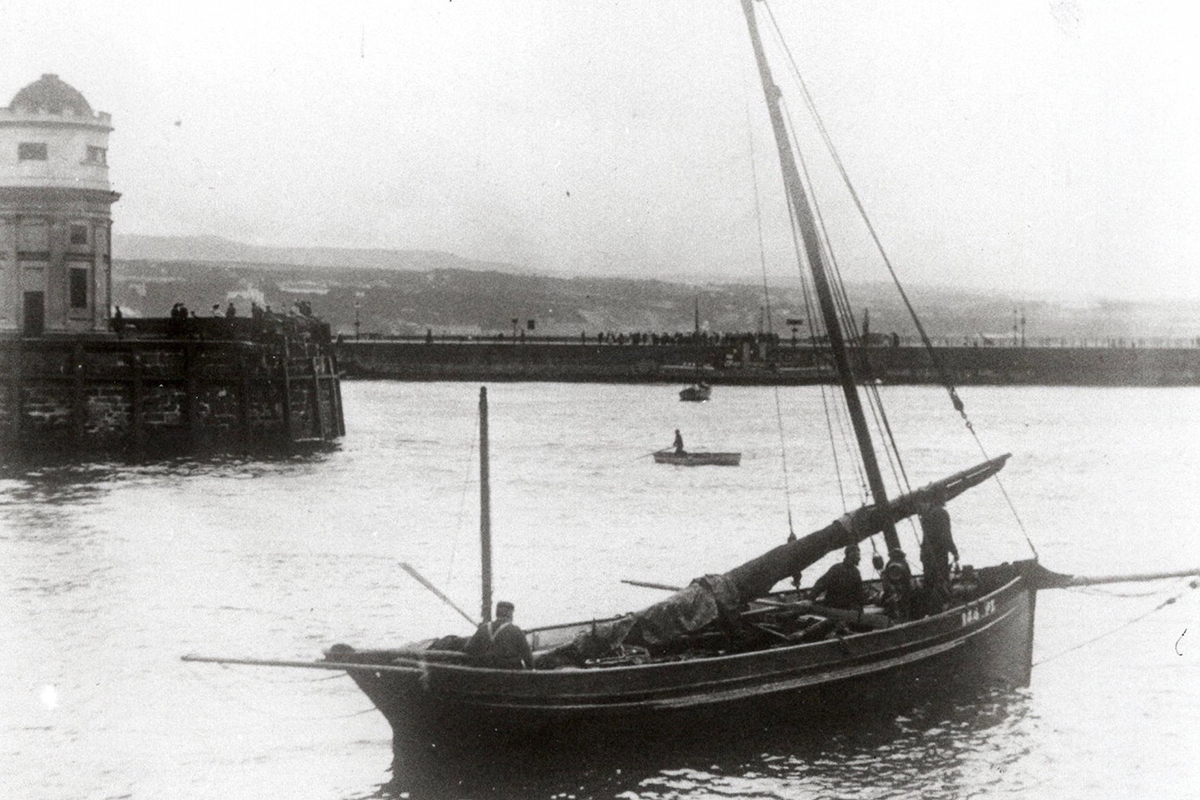

The fleet emerging from Peel harbour.

So great was the demand for these vessels that, as well as the Manx yards building them, William Paynter moved his works to Kilkeel, where he was able to supply both Northern Irish and Manx demand. At that time the average cost of a nickey was at least £700, including sails and nets.

In 1884, the first of the new breed of sailing boats appeared from the Clyde, heralding the first mutterings of another, and final, change in sailing fishing boat design. On the east side of the Clyde they called their vessels nabbies, whilst to the west they were Lochfyne skiffs. Similar in design, both were mostly half-deckers, and had steeply raked sternposts, upright stems, a sloping keel and one standing lugsail. This made them highly manoeuvrable, necessary when operating ring-nets.

The Manx Rose PL 48 and Manx Clover PL 47 unloading in Peel.

However, the Manx fishers weren’t generally taken by the ring-net, believing that this method would wipe out the shoals – which were already in decline. Some years in the late 1870s had been very lean for the Peel fishers.

But an improvement in fortunes in the 1880s saw the Manxmen copying the hull of the Scots boats, although wholly decking them over. These boats, which they called nobbies, were smaller than their predecessors at around 40ft. The rig had two masts, both with lugsails.

These continued to be built into the 20th century. However, by the outbreak of war in 1914, there were only 57 boats working from the island, about 30 of which had been motorised. The advent of the internal combustion engine was about to change the face of fishing everywhere.

The Achates LH 232, a regular visitor to Peel for the herring season, which was built at St Monans in 1947.

After the war the fishery declined, and it wasn’t until the 1960s that some respite was felt. But with the transition to clam fishing on the horizon, the Manx herring fishery never regained its former glory – as was the case elsewhere. Some fishing did continue, but its days were numbered.

How fantastic, then, to see a revival in 2023 with Marida DO 37, Jann Denise FR 80 and Our Sarah Jane CT 141 involved in fishing the small 100t quota, which will double in 2024.

A lift of herring being brought aboard the Our Sarah Jayne CT 141, one of the three boats to take part in the 2023 fishery. (Photo: Darren Purves)

Looking after today’s herring fishery is the Department of Environment, Food and Agriculture and the Manx Fish Producers’ Organisation, of which Dr David Beard is chief executive. His appointment as the new Admiral of the Manx Herring Fleet – after the title had been in abeyance since 1993 – hopefully heralds the return of a substantial fishery.

One hopes he’s happy at sea, as to wield power correctly, that is where he should be, raising his flag at dusk to signal that the fishing may begin!

St Matthew’s Day disaster

A fleet of scowtes sailed out to the nightly herring fishing on the fateful evening of 20 September, 1787.

At that time Douglas harbour consisted of little more than a pier, described as a ‘rude structure’, with a brick lighthouse some 30ft to 40ft high at its end, lighted each night by seven or eight half-pound candles with a tin deflector behind them.

In 1786, a gale demolished some 84 yards of this pier, including the lighthouse. A temporary lantern on a pole on what remained of the pier was all the boats had to steer in by. On the morning of 20 September, an unusually huge catch of herrings was landed.

In the evening, the herring fleet, numbering some 300 boats, set sail for the herring grounds off Clay Head and Laxey. One eyewitness was David Robertson, who noted the weather as being ‘beautifully serene, the sky pure and unclouded’.

But at midnight, ‘a brisk equinoctial gale arose’, and the fishermen began to dash home. One of the first boats

in smashed into the light and extinguished it, meaning there was no way for any boat to find the safety of the harbour.

“The consequences were dreadful,” said Mr Robertson. “In a few minutes all was horror and confusion. The darkness of the night, the raging of the sea, the vessels dashing against the rocks, the cries of the fishermen perishing in the waves, and the shrieks of the women ashore, imparted such a sensation of horror, as none but a spectator can possibly conceive.

“When the morning came it presented an awful spectacle; the beach and rocks covered in wrecks, and a group of dead bodies floating in the harbour. In some boats whole families perished. The shore was crowded with women, some in all the frantic agony of grief, alternatively weeping over the corpses of father, brother, and husband; and others sinking in the embrace of those, whom, a moment before, they imagined were buried in the waves.”

It has been determined from fishery returns that somewhere between 50 and 60 boats were either totally destroyed or rendered beyond repair. Twenty-one fishermen are said to have died. No wonder that these open boats were described as ‘our poor shells’.

This story was taken from the May 2024 issuof e Fishing News. For more like this, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.50 here.

Sign up to Fishing News’ FREE e-newsletter here.