The Mission’s book, Salty Cove, gives a glimpse of life for fishers and shore workers at Mevagissey. Phil Lockley paid the Cornish port a visit to find out more…

The choice of Mevagissey for the Mission’s latest fundraising book was timely. Mevagissey is testament to Cornish determination to fish for a living, and to continue doing so against all the odds. But those Cornish fishermen have a fight on their hands against factors beyond the weather and the tides: new fishing legislation on the one hand, and incoming wealth on the other.

As with most scenic British fishing ports, as fishermen are work-horses of the local community they once lived as close to the harbour as possible. But nowadays, as the scourge of second-home ownership in ports like Mevagissey grows, few fishermen live anywhere near the harbour. A countrywide demand for second homes has forced property prices so high that small-boat fishermen are being ‘driven to the hills’ – a local saying spelling out the fishers’ plight.

Mevagissey in 2021: the port is thriving – but is facing existential threats.

So being a true ‘Meva-man’ is (for most people) no longer possible. The days of being born there, raised there, and fishing from there are largely gone. But Mevagissey – today the second biggest fishing port in Cornwall – continues to nurture a strong fleet, with the potential of it growing further. Its harbour master, his staff and the harbour trustees work hard to protect the future of Mevagissey fishermen.

In days gone by, only natural factors controlled the local fleet. Nowadays, threats originating from desk-bound authorities hold it on a knife-edge. If a recently proposed gill-netting byelaw is enacted, at least 20 boats will be stripped from the Mevagissey fleet – potentially a third of its 60-plus registered vessels (Fishing News, 30 June, ‘CIFCA byelaw poses existential threat’). If that happens, the port’s infrastructure could collapse and be lost forever.

So now could not be a better time for the general public to see inspiring pictures and read uplifting text about the people of ‘Salty Cove’ – Porth Hyly, the Cornish name for Mevagissey Bay, translates as Saltwater Cove.

Port history

The first recorded mention of Mevagissey is from 1313 (when it was known as Porthhilly), but there is evidence of that settlement dating back to the Bronze Age. The old name of the parish was Lamorrick, part of the episcopal manor of Tregear. According to tradition, there has been a church on the same site in Mevagissey since about 500 AD.

Mevagissey is home to three holy wells. The Brass Well and Lady’s Well are both situated in the manor of Treleaven, and the third is within the gardens of the old vicarage, Mevagissey House. In the old days, all fishermen were strong church-going folk.

Towards the end of the 17th century, Porthhilly merged with the hamlet of Lamoreck (or Lamorrick) to make the new village. It was renamed Meva hag Ysi, after two saints: a Welsh man, St Mevan/Mewan and an Irish woman, St Issey or Ida/Ita.

At this time the main sources of income for the village were pilchard fishing and smuggling. The village had at least 10 inns, of which the Fountain and the Ship still remain.

In 1880, there were around 60 fishing boats engaged in the mackerel fishery; fisheries for herring and pilchards were also important. Pilchards were also imported from Plymouth for curing at Mevagissey’s sardine factory.

Mevagissey Harbour Trustees explain: “A medieval quay was first established in 1430 to give some protection to the seine fishing boats. By the 1770s, the trade had grown so much and the quay had fallen into such disrepair that it was felt necessary to provide greater protection for the fishing fleet and the village.

“In 1774, an act of parliament was passed allowing the building of the East and West Quays. Plans were drawn up by Mr Ploby of Stonehouse, Plymouth, and construction began using local granite stone. The total cost was £4,235, with the money raised mainly by the issue of redeemable bonds. 7

“During the mid-1800s, it was considered that an outer harbour should be constructed, and to this end the 1865 Harbour Act was passed. However, it was not until 1886 that construction started. This took two years and the cost is estimated at between £20,000 and £30,000.

“In 1891, the harbour was struck by a great blizzard. The storm destroyed most of the newly completed piers, and at least nine ships were lost. Rebuilding of the outer harbour started soon after, with a new design by Sir John Coode and largely financed by Mr Williams of Caerhays nearby.

“The works were completed in 1897, which also included a lifeboat house and slipway, which enabled a lifeboat to be launched at all states of the tide.”

Fifty years ago, the types of fishing and species sought were very different to today. At Mevagissey, longlining was a major fishery. Fish like ling, and high-priced turbot, were more plentiful than today, with relatively inefficient methods like passive longlining helping to conserve the stocks. Boats were built specifically for longlining – and the earlier pilchard drivers were used as longliners during the summer months, and were perfect for that fishery.

Once monofilament nets arrived in the UK, inshore fishing at ports such as Mevagissey evolved rapidly. At the turn of the 1970s, Graham Mills ordered the Blejan Eyhre as a longliner, and Freddie Turner ordered the Britannia IV as a potter, but soon after their launch both of those John Moor boats became leading gill-netters.

Mevagissey fishermen have played a leading role in the resurgence of inshore fishing in the West Country. When, in the mid-1970s, huge shoals of mackerel arrived off Cornwall, the South West mackerel boom began, with equally huge returns for fishermen spanning a decade. Some skippers saved their profits and later used those funds to develop the new static-gear fisheries that they or their children are involved in today.

The harbour in 1985.

By 1988, the Blejan Eyhre was a major player in monofilament gill netting from Mevagissey. To the rear, the multi-purpose Frances, a key old-style vessel in the Mevagissey fleet, was more multi-purpose, able to change methods to rhyme with the fish available – trawling one day, then, if required, gill-netting the next. Even 30ft boats like the Lucy Mariana were built to switch between handlining, static gear and trawling.

The Frances in 1987, when rigged as a gill-netter. At the rear of the group of vessels is Freddie Turner and John Leach’s Britannia V, built at Nobles of Girvan as one of the most advanced gill-netters of its day.

Skipper Freddie Turner, like many other Mevagissey skippers, was a pioneer in monofilament gill-netting. Below him is the Britannia V, a few days after its launch in Scotland.

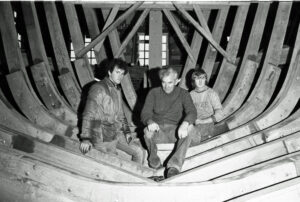

Mevagissey boatbuilder John Moor (centre) and his team on the first stages of one of his builds in 1984. The workmanship of John Moor and his son Peter (left) are praised throughout the fishing industry. A John Moor boat was at the top of the tree in its strength and finish – they were (are) works of art.

John Moor at work on the woods of a vessel destined to become a netter from Newquay.

Not only a top Mevagissey gill-netter, Graham Mills (left) was also a staunch supporter of hook and line fishing, and until his death held senior positions in the South West Handline Fishermen’s Association.

Due to modern-day restrictions, Mevagissey fishermen can no longer hold their trawler race – though they still (slowly) steam their boats alongside the harbour for those enjoying the Mevagissey Feast Week to see.

By 1988, even though using tarred cotton drift-nets was a thing of the past, here are Mevagissey fishermen clearing the nets after successful trials using the old method for pilchard – often found close to the shore.

Salty Cove: A labour of love

At a recent promotion for its fundraising book, Mission superintendent Julian Waring met Fishing News to introduce the volunteers who worked hard to see Salty Cove reach the bookshelves.

This is the third Mission book featuring fishermen and shore workers around Cornwall, and at 265 pages it is almost twice the size of the previous two. The Mission may set its sights for its next book further afield, and is debating how far north to go. The Shetlands have not been ruled out!

Each person featured in the book gives a short description of themselves and their links to the industry, and woven through the single-page tales are fascinating reflections from first-hand experience. Alongside this are superb black and white photographs.

All who participated in the production of Salty Cove did so as volunteers. Centre is Lauren Hunkin, a time-served Mission fundraiser whose inspiration gave rise to the book.

Although Mevagissey faces the same uncertainty as do all British fishing ports, Salty Cove is an upbeat book, transmitting the vibrancy of the port, its solidarity and its determination.

Julian Waring explained: “The first book, Salt of the Earth, was produced in 2014. The inspiration for that book came from Dave and Jan Penprase from Newlyn. They had already produced two fundraising books, and all work in making those books was done voluntarily. The funds raised went to the two hospices in Cornwall, each receiving £25,000.

“When I joined the Mission and became responsible for fundraising, I remembered how Dave and Jan Penprase had raised those funds. They came over to Newlyn, we met to talk about how we could do the same for the Mission, and the rest is history.

“The second book was produced on the same voluntary basis, and featured fishermen and the shore industry along the coast from Newquay to Port Isaac. That book was called Sea, Salt and Solitude.

“In this modern day and age, with so many things going on and things changing each day, it’s nice to see something like the Mission being constant in its aims – to help those in need within the fishing industry – and the Mission is efficient in doing so, because for every £1 generated by the Mission, almost 90p goes to those who need those funds – active fisherman, retired fishermen and/or fishermen’s families. I’m passionate about that, and about what the Mission achieves.

“Peoples’ interest in what the fishing industry is made of, how it works and what it faces each day extends far beyond Cornwall. Sales of those books have extended across the world.

Mission superintendent Julian Waring at the promotion of Salty Cove recently held at Mevagissey.

“The press likes good stories too, particularly radio and television, so we have excellent promotion, and our two previous books raised some incredible donations and awareness. Both the Mission and I are so grateful to those who gave their time, their energy and their talent to make this happen.”

The latest book was produced on a shoestring, with all but its printing costs saved through the dedicated work of volunteers.

It was inspired by Lauren Hunkin (then Brokenshire), who has been a Mission fundraiser for a number of years and set about recruiting a team of volunteers with the right skills. The book was written by Barbara Hocking, Jill Edwards, Julian Waring and Mark Sweeney, with photographs by Sally Mitchell and Matthew Facey.

In the first three weeks since publication, 500 copies have already been sold, raising £10,000 for the Mission.

Salty Cove is available to buy at Hurley Bookshop in Mevagissey, the Great Cornish Food Store in Truro, The Edge of the World Bookshop in Penzance, the Eden Project and the Lost Gardens of Heligan.

It can also be purchased from the Mission’s online shop here.

This story was taken from the archives of Fishing News. For more up-to-date and in-depth reports on the UK and Irish commercial fishing sector, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.30 here.