In the second part of a mini-series on the major role that North Sea cod played in the lives of generations of fishermen on the Yorkshire coast, David Linkie looks back on a day spent on the Whitby under-10m netter Roseanne WY 164 to observe a strongly conservation-focused technique

For a number of inshore skippers in northeast England, cod netting was a well-established part of their annual fishing pattern. Widespread hard bottom in close proximity to harbour, together with wrecks slightly further into the sea, were regularly populated by cod, for which there was always firm demand ashore. This provided an alternative fishery for skippers, some of whom were lifelong coble fishermen.

Roseanne was purpose-built for netting by Whitby boatbuilder Steve Cook.

This fishery was totally separate from that worked by larger 20m-plus wreck-netters based at Grimsby.

Operating on an uneven playing field in terms of quantity, inshore skippers relied heavily on catch quality to ensure that their fish attracted top market prices, and help them secure maximum returns for their efforts.

At the time of this trip, nearly 25 years ago, gill-net fishermen were already acutely aware of the threat posed by some environmentalists, who attacked gill-nets because of the threat of lost nets ‘ghost fishing’, and fed media hype on so-called ‘curtains of death’.

Another major concern was the latest EU proposed technical conservation measures, under which UK gill-netters would have to use specified minimum mesh sizes, with reference to the species being targeted, after 31 December, 1997.

A codling comes to the hauler.

Paul Kipling taking a small run of fish through the hauler…

Tom Jenkinson with a good cod.

A good run of sprags on the deck of Roseanne.

“Getting the highest price possible for your shot and doing the least amount of damage to the stocks on the seabed should be of paramount importance to fishermen. Why land an inferior product, with the constant worry that it will not secure a good price, or even sell at all?

“Skippers are then forced to try and compensate for low grossings by landing more fish, which only further weakens market prices. This leads to a vicious downward spiral, in that boats are using more gear and putting in more time at sea, which puts increased pressure on stocks without any tangible reward.”

Prime-quality codling associated with short soak net times consistently achieved top prices on Whitby fishmarket.

Grading the catch while heading in to Whitby.

Shooting away the first tier of nets from the transom pond.

These were the comments in the wheelhouse as skipper Roger Thoelen ran off north-northeast from Whitby into a moderate swell one early morning in August 1996.

His answer was to haul his nets as quickly as possible – five hours was the maximum time they were left in the water.

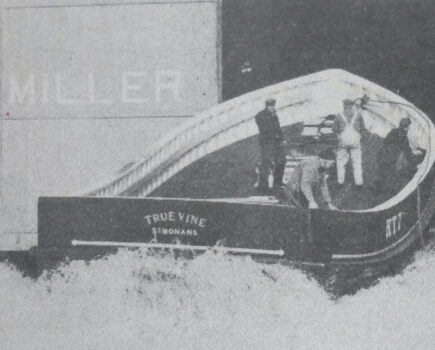

Roger Thoelen – a member of the NFFO executive committee and the Anglo-Scottish FPO – and his partner Tom Jenkinson had been putting these ideas into practice by ‘tiding’ since they took delivery in 1992 of the clinker-planked 10m Roseanne WY 164. She was built at Whitby by Steve Cook, and was designed to enable the fleets of gill-nets to be brought ashore each night.

Two large net ponds were arranged parallel to the transom, leaving plenty of space for a crewman to stand at either side of the ponds when flaking the nets. The first ends and dahns aboard from each tier of nets were unbent, coiled into boxes, and stored on a small cat catcher-style cradle above the transom. The last anchor and ends of each fleet were placed in a large bin amidships under the port side aluminium deckshelter, which had proved to be invaluable since it was fitted.

Why did the partners decide to drastically reduce the time their gear would be fishing, compared to that of the four other full-time gill-netters and several seasonal boats that fished from Whitby for mainly cod and turbot? Did that not put them at an immediate disadvantage?

“Definitely not,” said Tom Jenkinson, who laid out Roseanne’s fish on the market each night.

“Good fish tangled in gill-nets can quickly become damaged by crabs, seals and whelks, leading to a poor reputation ashore, reduced demand and low prices. The maximum time our fish has been in the nets is five hours, and often much less, so when fish comes aboard, it is nearly always live and in pristine condition.

“It’s good when steaming in to know that our shot will not only sell, but attract some of the keenest bidding the next morning, no matter what level prices are at. Our fish consistently makes over £1.50-£2/st above the daily market average for gill-net fish, so that is incentive in itself.”

Prices for good-quality cod at Whitby in the weeks leading up to this trip had been between £7.50 and £9.50 per stone, occasionally peaking at £12.50 (approximately £2/kg), comparing well with national averages. Roger Thoelen reported that fishing had generally been OK for most of the year, weather permitting, with encouraging signs of a good spread of mature fish on the grounds, indicating that cod stocks were healthier than at any time in the past few years.

Hauling the nets after three or four hours greatly reduces the quantities of rubbish and crabs which would otherwise become entangled in it, which soon reduces the gear’s catching efficiency. It also considerably reduces the potential damage to brown crab stocks. Less rubbish also means that the nets can be cleared quicker and with less damage, so the gear lasts longer.

Similarly, Roger Thoelen reported a marked reduction in £30 dahn ends and messenger ropes sacrificed to coasters heading for Teesside. And although local gill-net and trawler skippers generally worked well together, always being in the vicinity of his gear enabled him to fish in areas which would otherwise have been too risky.

Roger Thoelen said that one of the key elements in gill-netting was water quality. If that was not suitable, catch rates would be low. He believed that in certain conditions, fish lie dormant against the nets, unlike when they are chasing feeds, and plough into the tiers.

Roseanne generally fished hard ground, from close inshore in winter in 15 fathoms, to wrecks 40 miles from Whitby during the summer.

Eight nets were worked in a tier when ground fishing, although the gear was rigged so that it could quickly be shortened or lengthened, depending on the conditions.

The preference was for springier mono nets rather than the limper multi-monos, using all trammel nets with 30 mesh deep 4.75in x 0.45mm-diameter mono inner and 4.5 mesh deep 24in x 0.7mm-diameter mono outer walls. The nets were rigged in by the half to a pattern that Roger Thoelen had developed from 20 years’ experience.

Sourced from Selsey Fishing Supplies, the nets were set on a no. 4 braided leadline and 8mm braided backing line on the footrope and double 8mm polypropylene headline, with 6in bullet cellular floats every two fathoms. One fleet of trammel nets was usually replaced each week to maintain the gear in good condition.

For some years, Roger Thoelen had been using only monofilament trammels, which are highly successful in clear water, although they do not fish too well in murky water.

When conducting Seafish trials of gill-nets aboard Roseanne earlier in the year, skipper Roger Thoelen was asked to try nylon trammels. He was impressed with their performance in cloudy waters and had ordered a full set for the coming winter, but a drawback was that they could not be shot any faster than dead slow ahead – unlike mono, which can be shot at full speed.

He thought that the nylon nets continually fouled in the ponds because the mesh of the outer walls was dragging across the mesh of the inner section and snagging on the knots. This problem was addressed successfully by rigging a new net with a nylon inner and monofilament outers.

Skipper Roger Thoelen had been working 120mm mesh monofilament nets well before the EU proposal for similar-sized minimum mesh cod nets was introduced. His message to other skippers, particularly those north of the Tyne where a generally smaller run of codling predominated, was not to worry – 120mm was viable.

The trials that Roseanne had been participating in were organised by Seafish as part of an international three-year research project to measure the selectivity of gill-nets. Together with the square mesh panel trials carried out voluntarily on the Bridlington pair-trawlers Tradition and Ubique, featured in the first part of this mini-series last week, the netting trials illustrated the willingness of skippers to embrace measures that they thought would help to safeguard their respective fishing methods, and therefore their futures.

After running off for one and a half hours, skipper Roger Thoelen liked the look of some marks lying tight down along the ground edges 10 miles offshore. Four fleets of nets, including a double one, were shot away with the flood tide in a northwest/southeast direction almost end-over-end, in 30 fathoms of peaky ground.

To help trawler skippers identify fleets of nets, in line with a system the NFFO had implemented, the north ends were indicated by double flags.

Roseanne then steamed a further four miles north to shoot another two fleets, again along the ground edges, before putting a third fleet across a piece of hard ground that included some scattered wreckage. A 65lb plate was added to the anchor to ensure that this fleet dropped quicker into position and was not tided off. The final four fleets, including another double, were spread out as feelers three miles inside, to see if these areas would be worth further attention during the neap tide.

As Roseanne headed southeast to complete the day’s circuit, Tom Jenkinson and Paul Kipling rigged three hand gurdies. They normally spent an hour or so each day ripping while the trammel nets were fishing. As well as sometimes boosting the day’s shot by a couple of kit, this was also a useful test of fish on potential future grounds.

Skipper Roger Thoelen gutting…

But on this occasion the fish were not feeding, and after four stone of best codling had been hauled aboard, skipper Roger Thoelen called it a day and went to pick up the dahn of the first fleet of trammel nets.

A few codling and the odd sprag were soon coming aboard and laid amidships, keeping Paul Kipling occupied removing them, while Tom Jenkinson flaked the net into the deck pond under the Tarbensen 500/500 hauler. A duplicate set of Cetrek/Wagner steering and engine controls on the starboard gunwale aft of amidships enabled Roger Thoelen to see how the gear was leading and indicate to the hauler man when fish were coming up.

Six stone of prime-quality codling and sprags was the tally from the first fleet, which had been fishing for just three hours. This was considered a fair enough start, although the crew had higher hopes for the next tiers, which had been shot across better marks. From the moment the fish came aboard Roseanne virtually all alive, it was looked after to a high standard, gutted within minutes, washed and boxed.

The first fleet of nets was quickly hauled over into the transom ponds ready for shooting again, while Roseanne steamed to the second fleet. The catch rates started to pick up, with the second fleet yielding 11 stone and the third 12 stone of a similar mix of best codling and sprags. There was no rubbish in the nets, and only one crab was seen all day, so the gear was turned over aft very quickly and easily.

Hauling went smoothly, with small runs of fish keeping the crew on their toes and the best fleet yielding 18 stone, but the highlight of the day was yet to come. After a characteristically slow start until the wreckage showed on the sounder, large cod and best sprags, plus the odd ling and pollack, started to tumble aboard.

Large ‘four-to-the box’ cod and ling showed the flexibility of the trammel nets to take the full range of marketable fish. Only two immature codling were hauled all day, proving the conservation benefits of netting.

… and washing a ‘four-to-the-box’ cod.

Nearly 50 stone of fish was soon lying on deck from the jackpot nets, and with the last fleets contributing a good run of codling, Roseanne headed for Whitby after a 13-hour day with an above-average 13 kit (130 stone) shot aboard – testament to the hard-won local knowledge and experience of her skipper and crew.

Grading while steaming in showed a mix of cod, best sprags, sprags and best selected codling. The fish was quickly weighed on Whitby market and iced to maintain the Roseanne’s reputation for landing top-quality fish – quickly acknowledged by Dave Winspear of Alliance Fish, skipper Roger Thoelen’s selling agent.

The following morning, Roseanne’s best cod secured £12.50/st.

Two days later, a plentiful run of smaller sile-rich codling, landed by the inshore netters from nets left overnight, struggled to make £4.50/st, while another shot of same-day fish landed by Roseanne made £9/st on a well-supplied market.

But within a year or so of this trip, Roseanne was sold to Bridlington and rigged for potting, before later moving to Shetland, as the door closed on another conservation-focused fishing method that had provided valuable diversity along the northeast coast of England.

Next week: Whitby trawler Carol H targeting top-quality cod on local inshore grounds