True or False

Here’s the second part of a squid diary inspired by the BBC Radio Four programme, ‘In Our Time’, in which the myths and tales about octopuses, squid and cuttlefish were discussed by three leading scientists

Led by presenter Melvyn Bragg, the scientists revealed how these species of cephalopods are the weirdest yet the most adaptable of almost all animals, and that a lot of the myths about them are firmly rooted in truth (Fishing News, 24 May).

The scientists were:

- Dr Louise Allcock, a lecturer in zoology at the National University of Ireland (in Galway)

- Paul Redhouse, honorary professor in the Department of Zoology at the University of Aberdeen, and marine living resources scientist for the British Antarctic survey

- Jonathan Ablett from the Department of Life Sciences at the Natural History Museum, London, where research into the zoology of molluscs includes the adaptability of cephalopods

Apparently, cultures around the world have stories of giant octopuses and/or giant squids, and many might be ‘stretched truths’, but some contain hard and frightening facts.

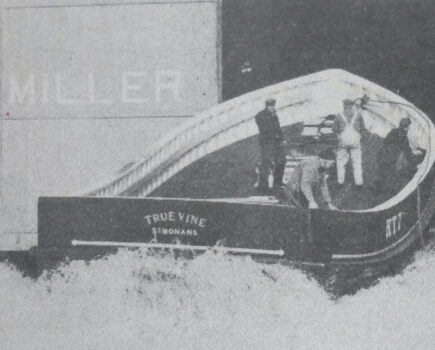

Main image: Was it the Kraken of Falmouth Bay? Not really, but it was my biggest that year, 2013, with a mantle length of 52cm and a weight of 5.2kg.

Jonathan Ablett said: “Such myths in culture are everywhere that there is sea, but particularly in regions like South East Asia, the Caribbean, also in Greek mythology, and of course the mythical sea-monster called Kraken in northern Europe. All these tentacle-like sea-monsters represent the once-unknown facts of such fascinating creatures. Looking at it, they are indeed alien to land animals like us.

“And if you were walking along a beach, and saw part of a big cephalopod washed up, it is difficult to not imagine a gigantic animal, a terrible beast; and even in modern culture – depicted in films like ‘Arrival’ in 2016 – when the alien species that landed on earth was cephalopod-like, having seven arms, and those aliens squirted ink to communicate, so even today we think cephalopods are fascinating, yet they are indeed alien to us.”

Discussing how cephalopods can change their colour, Dr Louise Allcock described how living on seabed materials like reefs, rocks and even sand, camouflage is required to prevent being eaten.

The jig teeth are well-attached to the centre bar, and note the dip of resin at the base to give extra hold. For me, these are the type of hooks and shafts that should be on all jigs – in one piece.

She said: “To do this the cephalopods use chromatophores, little coloured cells present in their skin, cells surrounded by a ring of muscles. In the relaxed state, those muscles close over the coloured cell, but when contracted, the muscle allows the coloured cell to become visible.

“But there are only three different colours of such cells, yellow, red or brown – but that fact doesn’t mix with what we know about the colours that octopuses, squids and cuttlefishes can show off, a magic array of colours.

“Other structures deeper in the skin, called iridophores, reflect light. Within the irodophore is a protein called reflectin, a molecule that stacks itself in layers, and depending on how close together those layers are, they reflect a different wavelength of light (producing different colours).”

Dr Louise Allcock explained how the skin surface of many cephalopods has muscle cells that can either bunch together or flatten to make the animal’s body surface replicate the seabed surface. And with all of that complexity, the animal can change its colour and texture in as little as 200 milliseconds. Although all of this may be used as a means of communication, principally it is used as camouflage to prevent being attacked.

Honorary professor Paul Redhouse spoke about cephalopod eyes, particularly cuttlefish eyes, which are huge in relation to its body size, saying that most cephalopods have a very sophisticated eye, one similar to the mammal eye, and an example of convergent evolution. He added: “In practical terms, very different structures have evolved to do almost exactly the same thing – advanced eyesight underwater, and with mammals, above water.

“Cephalopod eyes have a pupil to control more or less light coming in, but one which is square, and not round like ours. Like us, they can change the pupil size.

“And although the cephalopod eye has a lens similar to a mammal eye, instead of changing its shape to focus the image, it moves forward or backward. The cephalopod eye operates like a camera lens, rather than like a vertebrate lens, which changes its shape.”

He added something that I find difficult to believe, though I have no doubt of its scientific validity – that most cephalopods are indeed colour-blind!

Science reveals that the cells on a cephalopod retina are very different to ours. So, as squidders, are we wasting money on different colours of squid jigs? Would different variations of grey do the same as those lovely-looking variations on my favourite DTD jigs? Is it brutally true that squid jigs – like pike lures and/or trout flies – fool more fishermen than fish?

But, as I warned you about trying squid jigging – or indeed, trying to fool cuttlefish by using coloured plastic shapes in a trap – you will become addicted to the task, yet end up with more questions than answers!

This Hikaru jig might be very effective, and is so cheap that replacements won’t break the bank.

BBC ‘In Our Time’ went on to ask how most squid and cuttlefish that can change their colour, are colour-blind, but can clearly tell the difference between slight colour changes.

The scientists gave the example of the legendary Humboldt squid, which uses red in aggression, and discussed how these predatory squid (found in the Eastern Pacific, from California down to Chile) are pack animals, often attacking prey in a co-ordinated manner. Confirmed reports reveal that on occasion, Humboldt squid have attacked and killed fishermen and/or divers.

“They are not aggressive all the time, but do get into a feeding frenzy if a human gets in the way of the fish they wish to eat,” suggested Jonathan Ablett.

He said he can’t believe that monster squid have dragged down boats, but can imagine how an unpredicted change in the behaviour of a cephalopod might conjure up such myths and legends.

“These animals are not only eating, they can also be defending themselves. Some species of octopus are even venomous – the venom is in their saliva – so when they bite their prey, the venom is injected, and either paralyses the prey or kills it. They may also use the venom to soften the tissue they are about to digest,” he said, and went on to describe the ‘one bite kills a human’ octopus – the blue ring octopus – and how true it is that one small bite can be fatal.

At this point I became very aware of how little I know about cephalopods – and that is sad, really, because I spent three years studying marine zoology at Bangor in North Wales. Clearly, I spent more time long-lining for bass or serving pints in the pub than I did reading books!

‘In Our Time’ went on to explain jet propulsion used by squid, cuttlefish and octopuses, and how cephalopods have complex taste cells on their tentacles.

All sorts of easily-understood facts painted a beautiful picture of the very animals that I chase for money – or am I going a bit soft in my old age? Yesterday, I made ready for my first try for squid, and remembered what a Newbiggin skipper once said to me – if, when you start the engine, a small pair of red horns don’t grow from the back of your head, don’t go fishing, go home!

From my diary (of 2009), the earliest squid I caught was from the pit near the Helford river on 22 July, but don’t get too excited – it was so small that I returned it!

The front is also well-made – a strong squid jig – and although in heavy fishing the body will become ripped, keep all of the shafts and tie your own, or mould your own jigs. For little retail cost, this jig has lots of potential.

However, my advice is to check your squid gear, retie the traces, and consider buying more jigs. Don’t wait until late September as every jig will be sold, because there might be a decent season ahead. And this is only my opinion – squid jigging goes in cycles of feast or famine, and the last ‘feast’ was in the autumn of 2013, so it’s long past time that we had another hit of good luck.

And lastly, consider this, a jig I have never seen before – a super-soft glowing rubbery jig made by Hikaru (Japan). It’s not expensive (under £3), but it is a strong jig, based on a one-piece mount made of stainless steel, with a brass weight hidden inside the body.

It is available from Newtown Angling Centre near Penzance (01736 763721). If you want a couple to try, order them now, because shop owner Chris Bird still has a few in stock (plenty more are on order).

Bass fishermen also use them, I was told, by removing the spikes and replacing them with a single treble hook.