Notwithstanding the current crisis, fishing today is a lot easier than it used to be. John Worrall delves deep into Norfolk fishing history

Consider this. On an early spring day, in a small creek on the east coast of medieval England, you climb aboard a blunt-nosed wooden boat, maybe 40ft long, a veritable tub of a precursor to the more elegant North Sea sailing stock that would develop. It comes with similarly unrefined propulsion – a single square sail – and likewise its steerage, which is an oar over the quarter.

The village of Cley, just downstream of the bank that spelled the end for the Glaven ports – along the line of which the coast road now runs.

In this, you and perhaps two dozen shipmates sail to Iceland. There you spend the summer on a diet of biscuit, bacon, beer, cheese and pease, dangling two-hooked hand-lines for cod and ling, which you hand-haul and then salt, bringing them back in late summer to that creek, from where other boats will take them on to southern towns and cities, not least London.

It could have been worse – it could have been an open boat. Word of the riches to be found in the Icelandic seas had come with the Vikings, and for a while, Icelandic trips would have been made in derivatives of their boats, with commensurately high loss rates. Only in the 13th and 14th centuries had a semblance of cover for the crew, and even decking, become the norm – but the basic summer routine of sailing north continued right up until the 19th century.

It was a tough annual grind. It is said that a lad who had his 12th birthday in Iceland might not have another birthday in England until he retired – if he lived that long. Many such trips were made from eastern England, particularly from the small harbours and havens of Norfolk and Suffolk. They included three ports, Cley, Wiveton and Blakeney, clustered round the then relatively wide estuary of north Norfolk’s little river Glaven.

These days, the Glaven no longer has a wide estuary, and is better known as one of the world’s only 200 or so chalk rivers, while Cley and Blakeney are full of summer visitors and second homes. Lower-profile Wiveton is that of Wiveton Hall and the TV show Normal for Norfolk.

The three ports grew in the shelter of the westward-running sand and gravel spit known as Blakeney Point, which – on an otherwise mostly exposed and shoal-ridden coast – was a good place to run to in anything from a northerly quarter. In medieval times, the point was shorter than it is today, having not yet extended west of Blakeney itself, but it gave plenty of protection to the other two ports.

Blakeney still has a channel, and some boats – but not for fishing.

Cley sat on the eastern side of that estuary and Wiveton on the west, while Blakeney lay up a creek a mile or so to the west. The channel to Cley and Wiveton, scoured by tidal run-off from salt marshes, allowed ships of up to 130t to nose in on the flood and sit on the mud in front of Cley church and Newgate Green, or under the churchyard wall over at Wiveton. Ship-owners tended to live at Wiveton, leaving crews to live and carouse in slightly downmarket Cley.

Prime-time for all three ports was in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, when East Anglia had grown rich on the back of the sheep. None was a wool staple port, so they couldn’t handle wool, but Norfolk barley went out and coal, timber and salt came in. The salt for those fishing boats was measured in ‘weys’ – a wey being enough to salt 1,000 fish. The best quality came from the Biscay coast of France and Spain, and if that wasn’t available, poorer stuff from northeast England and from Scotland – then still a foreign country.

For those Glaven ports, fishing was the main business in the 15th and 16th centuries. Their boats would set off each spring, paying for prayers to be said by the hermit in his chapel on the marshes – the nearest thing they could get to insurance for small ships in Icelandic storms.

Boats ranged from crayers and lodeships up to cogs, but fishing boats were mainly doggers – a word of Dutch provenance, and a generic term covering a range of sizes and designs involved with fishing and occasional trade, broadly running from 30t to 100t. As late as the 14th century, some may still have carried oars, because the Mary of Cley, pressed into service in 1373 by Edward III, had a crew of 30, which suggests rowers. They gave their name to the Dogger Bank, although exactly when isn’t clear – the earliest reference is probably in 1666, when the London Gazette mentions ‘some few dogger boats plying about the Dogger Banks’.

Looking across from Cley churchyard to Wiveton. What is now meadow was once the harbour, where ships of 100t or more nosed in.

Impressment was an occupational hazard for ship-owners, because in times of war, with no professional navy, the king requisitioned ships wherever he could, and owners were constantly looking for excuses not to comply. Glaven ships usually got away with it on the size criterion by which those not able to easily carry 16 horses were exempted.

The Iceland trip could take from something over a week to a fortnight or more each way. One reported passage in 1540 took eight days from Iceland back to Cley, averaging over 100 miles a day – but for that, the square sail would have needed a fair wind.

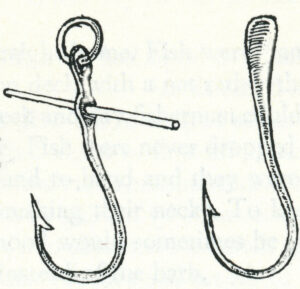

They fished from 20 to 70 miles off the Icelandic coast, which may have been in order to stay away from a lee shore with such a basic rig, and hand-lining was done in deep water, perhaps 50-60 fathoms, and sometimes twice that. For that reason, longlines were less practical, although they did feature at times – because in 1500, with English boats getting bigger, the Icelanders were protesting that the English, with their large craft and longlines streaming down the tide, were spoiling the fishing for the smaller local boats.

Those bigger English boats deployed their own small craft for greater spread of effort. Fish were brought to the surface, hauled aboard with a ‘hawk’ – a gaff – and then banged on the head, which is where the generic term ‘codbanger’, for cod fishermen, came from.

But trips were often trading missions as well. Henry VIII was advised in 1533 that from ‘Norfolk and Suffolk and other parts of this your realme of England 100 sail… do go of merchandises and doggerfare for ling, cod and stock fish’.

The estuary widened to where Cley was relocated.

‘Stock fish’ were cod that had been split and hung on a bar in pairs to be air-dried, a process that took three or four months and was a winter job. The end result was a club of fish hard enough for a Tudor Blackadder to beat Baldrick over the head with after another cunning plan – but it was mostly done by Icelanders, and traded for corn and cloth and other things the island couldn’t produce. Back in England, it was half the value of salt cod, which eventually predominated.

Iceland had always been short of consumer goods, more particularly after it was subjugated by Norway in 1263. All trade then had to go via Bergen, where it was so heavily taxed that it died out. And then, at the end of the 14th century, Iceland and Norway both came under the domination of Denmark, and Iceland was more or less ignored by the other two, leaving it more impoverished. So the English ignored Bergen and reverted to trading direct.

But as traders, they entered the domain of the Hanseatic League, the north German militaristic trading cabal, which was at the peak of its powers in the 15th century and took every opportunity to rub out competition. On one occasion in the early 15th century, 100 or so fishermen from the Glaven and Cromer who had taken refuge in the Norwegian port of Wynforde were attacked by 500 armed Hanse, who bound them hand and foot and threw them into the sea.

There was anyway a high attrition rate from the elements among English crews. When the Little Peter of Cley was driven from Iceland by a storm, it washed up on the Norwegian coast with only 13 out of 34 still alive. And there were the usual problems of crews getting killed in brawls with Icelanders or the Hanse, or among themselves. Men getting injured or falling ill were left ashore, and had to make their own way home.

Shipping was once the main business in the three villages – as evidenced by graffiti, reckoned to be 17th-century, in the choir stalls in the church at Salthouse, just to the east.

Then, when boats got home, there were financial hurdles, because in a time before taxation, they had to pay ‘composition fish’ to the crown, which was entitled to 100 choice ling – and the church also got a cut, the parson’s divvy being known as ‘Christ’s dole’. This caused trouble in north Norfolk in 1591, because the parson at Wells, along the coast from the Glaven, demanded it from any fishermen who called in, and yet when they got to their home port, they still had to pay their own parson.

But in the 16th century, those catches were nevertheless substantial. On one day, 27 September, 1587, over 60,000 cod and ling were shipped out of the Glaven in five vessels: the Magdalen of London with 10,000; the 30t Jonas of Cley with 12,000; the 40t Mathew of Blakeney with 14,000; the 40t Peter of Blakeney with 15,000; and the William of King’s Lynn with 16,000.

In addition to the weather – a strong northerly would pepper the Norfolk coast with wrecks – there were pirates, the Scots being a particular problem, and depending on international relations at the time, there were privateers. These were ship with ‘letters of marque’ from a head of state that authorised them to attack shipping of an enemy state. And in those days, most states had enemies. One group of privateers working out of the Swedish port of Marstrand caused a lot of bother.

Mind you, north Norfolk had a few of its own, notably the Cornishman Henry Carew, who came up for a spot of privateering in 1575-76, partly because his sister was married to Sir Christopher Heydon, who lived in nearby Baconsthorpe, but more particularly to attack Flemish vessels from the Glaven. The fact that England wasn’t at war with the Flemings at the time didn’t bother him unduly; he simply got his letters of marque from Spain, which was.

This, however, was something of an irritant to the court of Elizabeth I, what with the disruption to Flemish trade, and more particularly him getting letters from Spain of all places, because this was only a decade before the 1588 showdown with the Armada. A royal proclamation soon stopped English mariners serving foreign powers.

Smugglers also liked those small north Norfolk ports with their thin officialdom and credulous populations, happy to ‘watch the wall, my darling, while the gentlemen go by’. Baccy and booze, notably Dutch gin in stone bottles, were prime cargos, and were often landed under diversionary ruses such as flying a flag to indicate contagious diseases onboard – cholera was endemic – or invoking the legend of Black Shuck the Dog, saying that the hound – a sight of which was supposed to mean imminent death for the observer – was out on the marshes.

The hooks on hand-lines sometimes had a pin to prevent the cod swallowing it completely.

But by the beginning of the 17th century, the Glaven ports were losing market share. Ships and fishing boats were getting bigger and more efficient and the Glaven estuary was relatively small and, more particularly, away from commercial centres. The cod fishery on the Dogger was also getting more attention from Harwich and Grimsby boats, which could reach consumers direct.

In the second half of that century, the Dutch came up with the idea of well holds for bringing back live fish. Wells would be filled towards the end of the voyage when the boat was about to head home, and each fish was brought onboard with a net, rather than the hawk, and put into the well tail first to avoid breaking its back. Normally the swim bladder had to be pricked, but if Iceland cod were pricked, they tended to die, seemingly because of the depth from which they had been hauled, and so the air was massaged out of them.

Longer voyages had lower survival rates, because rough weather could bang the fish against the deck or well sides, while calm weather could suffocate them – but fish could otherwise live a long time in the well. If one was overlooked at the end of a season, it could still be found swimming around months later.

There’s nothing to show that the Glaven boats ever used wells – nor it is likely, because the three ports remained villages with no commercial hinterland, and boats waiting for fishermen to return from Iceland, to take the catches south, wouldn’t have had wells.

But in any case, two 17th-century events changed the Glaven – and Wiveton and Cley in particular – for ever.

One was the almost total destruction of Cley by fire on 1 September, 1612, when 117 buildings were destroyed (in a sign of the times, the whole lot were collectively owned by just 17 men and women). The village was rebuilt half a mile downstream, where there were probably already some quays, and although that move had its compensations in the light of the second event, these weren’t enough to stave off what was probably inevitable.

The Glaven coming down from Cley. You probably wouldn’t get a 100-tonner up there these days.

In 1637, the lord of the manor, Sir Henry Calthorpe, decided to reclaim a big chunk of the estuary for grazing by building a bank across it, with a sluice for the Glaven. Although, two years later, he was ordered by the Privy Council to pull it down, the lack of tidal scour had already silted the channel. Wiveton, which had hitherto accommodated ships of up to 130t, ceased to be a port.

Cley’s move downstream after the fire put it below the bank and gave it a stay of execution, but the much-reduced scour allowed silting, which eventually did for it too. With trade increasingly looking to the New World, and the Industrial Revolution later happening elsewhere, the Glaven ports slipped from significance.

Blakeney did revive a little in the 19th century with the straightening of its channel, but at Cley, another land-grabber’s bank, built under the Wiveton and Cley Enclosure Act in 1824 on roughly the line of the first, finally finished it as a commercial proposition. Robbed of even its now modest tidal scour, the port silted further and closed to any decent-sized craft.

So these days, the erstwhile Glaven fishing ports are three flinty coastal villages with only a few physical remnants of busier commercial times – including, interestingly, a scattering of cannon, said to be from the Napoleonic wars. Blakeney retains modest maritime action with leisure sailing and seal-spotting cruises, while Cley has gone for birding, its marshes more or less top of the premier twitcher league. Indeed, the Cley marshes were bought in 1926 by the Norfolk Naturalists’ Trust, now the Norfolk Wildlife Trust, which was formed for the purpose and became the forerunner and template for the 40-odd Wildlife Trusts subsequently established around the country.

Wiveton, meanwhile, robbed of its waterfront, has receded into the trees and bushes, separated from Cley by meadows that were once the estuary, and through which the little Glaven now flows almost unseen.

Further reading:

The Codbangers by Hervey Benham, 1979

The Glaven Ports by Jonathon Hooton, Blakeney History Group, 1996