The seventh article in the series by Hull skipper William Oliver, first published in 1953/4. All photographs courtesy of Alec Gill

One beautiful summer morning in late July 1914, I was fishing on Dyra Fjord Bank, a ground 25 miles NNW from Dyra fjord. We were alone and had landed two very good trips from there. I was having a sleep about 3am (it is light all night during the summer) when I was called by one of the crew, who told me a large salvage tug was coming to speak to us. It was a Norwegian vessel, the Norge.

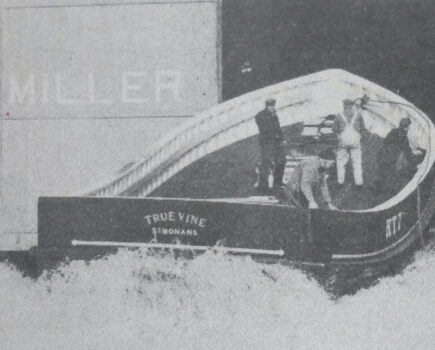

Most of the deep-sea trawler fleet were requisitioned for minesweeping duties during the First World War. The Hull trawler Ferriby, with a gun installed on her whaleback, was one of many.

The skipper hailed me and said he had been instructed by my owners to tell me that war was imminent between England and Germany. We were to call at the Orkney Isles for routing instructions before proceeding along the North Sea. We were dumbfounded. There had been something in the papers when we left home about some archduke or somebody being assassinated, but we didn’t pay much attention to it, as it seemed too remote to make any difference to us.

I confess at the time I didn’t know what to do. In the first place, as a Skipper RNR, I considered I was very lucky to be at sea when this happened, otherwise I should have been called up. So I decided to stop fishing to save my coal, and anchor in Dyra fjord for a week or two, when the war would be over, and I should be able to catch my voyage and proceed home. This we did; at any rate, we steamed into Dyra fjord, and should any of my readers think that I was an idiot, I can say only that vessels were steaming in from all directions.

Ultimately, there were about 25 of us in Dyra fjord, and the stories we heard from the Icelanders were fantastic. London and Paris were reported in flames, while big naval battles were being fought in the North Sea, etc. We were sure that it would be only a matter of a few days before it was all over. After about a week, the trawler St Ives H 11 arrived from Hull, with the late George Brewer as skipper. He had a very large selection of newspapers onboard, which he shared out amongst us. When we saw that war had not even been declared yet, we all felt extremely foolish, and without any further delay left the fjord for the fishing grounds.

It took us a week to complete our voyage, and we then left for home, calling at Stromness for routing instructions. We came south along the land in the ordinary way, except that we were instructed to fly the Red Ensign, and also to report to the examination vessel off the Humber before proceeding up the river.

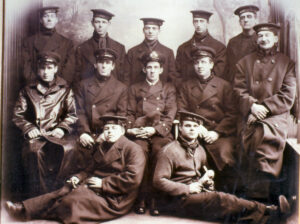

The crew of the minesweeper Rosy Morn. Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) trawlermen working on minesweepers were colloquially known as ‘Harry Tate’s Navy’, and their rough and ready ways often clashed with the strict discipline and spit and polish of the regular Royal Navy. However, naval officers and ratings soon came to respect the trawlermen’s seamanship, courage and skill at handling the minesweeping gear

I had purposely arranged to land on a Saturday, to enable me to snatch a weekend at home before reporting for service. We landed on Saturday, 22 August, and made £584. We learned, of course, that our army hadn’t even landed in France, and apart from some mining activity, hostilities had been negligible. I reported on the Monday, and was told to go home and stand by for orders.

I saw Mr McCann and, discussing my mobilisation, he suggested that if I was away from fishing for over three months, I would have to start a fresh year for bonus, but that under three months, the money earned by whoever took my ship would be counted in my favour. Mr McCann was quite convinced it would be well over by Christmas, so I went away with a good heart.

On the next day I reported again, and was ordered to Sheerness by the next available train, and to present myself and report to the senior officer of minesweepers there.

Fishing for mines

Of my war service from August 1914 until January 1919 I propose to say very little, as I don’t suppose it differed from that of hundreds of others. There are, however, two or three outstanding experiences worth relating. I was engaged in minesweeping the Thames estuary from August 1914 to August 1915, and naturally obtained a very good working knowledge of the various sandbanks and channels in that vicinity.

For about eight months, we never had any trouble with mines, and then we got them thick and fast. Vessels started to go up nearly every day, and on one occasion I was sweeping when a patrol trawler named the Scott (H 968) was about to hail me with a verbal message from the senior officer. The skipper of Scott actually had the megaphone in his hand when she struck a mine quite close to us. In one minute, there was nothing left, and only two were saved out of 14.

As my wife and I had not been able to have a holiday in 1914, I arranged to rent a furnished house in Sheerness for her and our family. While we were there, the first Zeppelin raid took place over this country. I had arrived in port one morning, and after coaling and watering the ship, moored to the buoys and obtained leave.

A gun crew working on a trawler converted for minesweeping duties.

We went out, I remember, in the evening – to the Hippodrome in Sheerness – and after having a glass or two of beer, went to bed feeling very sleepy. My wife woke me about 2am. She said she could hear heavy gunfire. I thought it was either thunder or gun-testing at Shoeburyness, and went off to sleep again. But after another crash, we got up, roused the children and took them all into the garden. We learned afterwards that a Zeppelin had raided Eastchurch, not far away. An air raid is a commonplace nowadays, but then it was a weird experience.

As the war dragged on, more and more trawlers were taken over by the Admiralty for minesweeping and patrol service. Several trawlers fishing had been sunk by mines along our coasts, one of the first to go down being a Hellyer’s vessel, Imperialist H 250, which hit a German mine on 6 September, 1914 off Flamborough Head. Her skipper, Joe Wood, one of Hull’s foremost skippers, was lost aged only 42.

In August 1915, I was skipper of a Grimsby trawler, the Tokyo GY 167. During a routine trip, we were suddenly recalled from sea and ordered to fill up with coal, water and provisions, and stand by to proceed to an unknown destination. I made discreet enquiries, and learned we were bound for Malta.