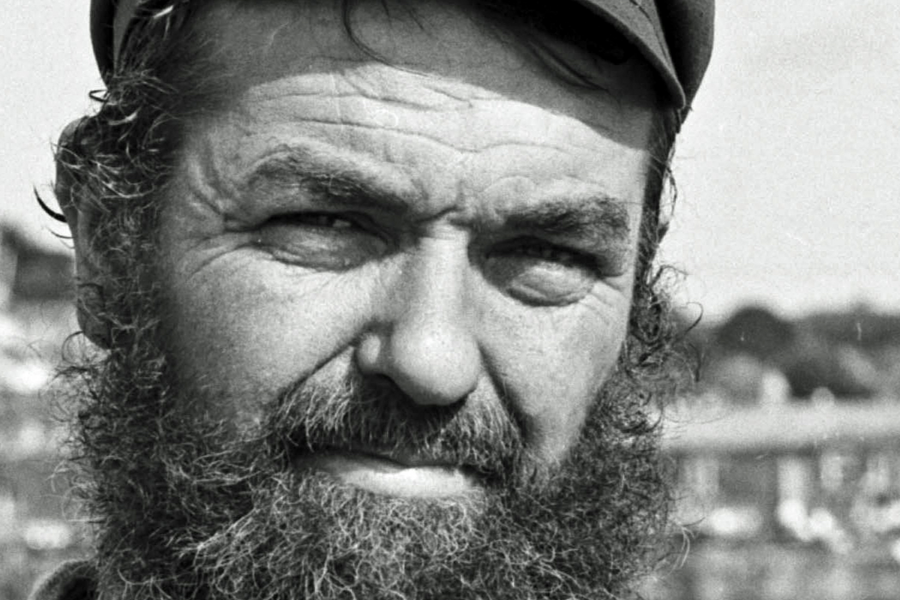

Why is trawlerman ‘Grimmy’ Mike Mahon going home to Grimsby? The former Newlyn skipper speaks to Phil Lockley, in the first of a three-part series

He is loved by most, politically feared by some, and annoying to others – but when Newlyn skipper Grimmy Mike Mahon (70) gives his opinion, few ignore what he says.

For decades now, Grimmy has been gnawing away at the political core of European and British fisheries management.

He is known to all as ‘Grimmy’, though quite why Grimsby calls him now is anyone’s guess. Surely, after 40 years of operating in Cornwall, Grimmy is no longer an ‘emmet’ (incomer), but an adopted Cornishman? Cornwall will be a lesser place without him.

One of the best-known inshore trawlermen in the South West, for the past four decades Grimmy has been a delight to local and national media. Grimmy has often been my tutor in the subject of fishing politics; there’s not a lot that he doesn’t know about the failures of the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP). His opponents rarely challenge Grimmy’s off-the-cuff responses, and with a barrage of facts, he can shoot down any claims uttered by Remainers.

His never-ending exploits were underpinned by his wife, Joan, who recently passed away. Joan was often the powerhouse who kept Grimmy on course to hammer away at the plight of British fishermen under the control of Brussels. It was costing Grimmy a lot of money in lost fishing time, and he admits that he often had thoughts of giving up, but Joan would not allow that. Joan knew all of us in the media on first-name terms, and when picking up the phone, never said, “I’ll pass you over to Mike,” but, “How are you, Phil?” and chatted about whatever was topical before giving the phone to Grimmy.

His last trawler, J-Anne BRD 92, just 29ft long with its forepeak, was strewn with newspapers and books. Until its decommissioning, J-Anne was a floating political library.

After selling Joal to Joe O’Connor, Grimmy bought the 41ft steel trawler Betty G, but was later forced to decommission it and replace it with the 29ft J-Anne.

Grimmy was threatened countless times by MAFF (MMO), yet each time he walked away with nothing more than a warning. Any other fisherman might have faced bankruptcy from the fines imposed, but Grimmy had the upper hand. He often taunted the authorities; he knew when to strike, and the local media (including myself) simply lapped it up. We all sat there waiting for the MMO to pounce. But, in truth, most fishery officers agreed with Grimmy, and quietly supported him.

Grimmy wasn’t alone in fighting the treachery of the CFP. Often his mentors were the Hastings fishermen, and when their leader Paul Joy set about attacking the dumping of fish, Grimmy did the same, and goaded the Newlyn MMO to watch him doing so. The MMO couldn’t stop him; Grimmy just gave the over-quota fish away. Once he began a spell of giving fish to the Mission, and openly defeated the fishery officers when they prepared to prosecute the Mission for being party to handling ‘black’ fish. No contest.

I have seen several MMO district inspectors rise and fall through the reign of Grimmy, and in my opinion, whatever wage the government paid them wasn’t enough. Time and time again he wiped the political floor with them. Grimmy is now a feisty, retired fisherman, one who was never really defeated. And if the MMO believes it is waving goodbye to Grimmy, think again – he’ll be in Grimsby soon!

I recently had the pleasure of joining Grimmy for a walk down memory lane, to hear how he – once a parliamentary candidate for UKIP – never gave up his fight against the tyranny from Brussels.

Grimmy’s story

I always thought that Grimsby was Grimmy’s birthplace, but it wasn’t. Grimmy never had a true ‘home’, and was born in Aldershot. His father was a warrant officer in the army, so Grimmy’s family often travelled around the globe.

“As a kid, I was what military folk call a ‘service brat’. I lived all over the world; Singapore for three years, Libya for three years, and was then taken to Grimsby.

“Even Dad didn’t stem from Grimsby. Before he met Mum, he was a professional footballer in Ireland, and before the Second World War, he came to the UK to play for Arsenal, and he met my mum. He wasn’t happy to be in the Arsenal reserves, so just one year before the war broke out, he left Arsenal and joined the army.”

Grimmy ended up working from Grimsby on sidewinders, not to become a career fisherman, but to save money to get himself to college and become a teacher or architect. It wasn’t to be.

“When I went to sea from Grimsby, yes, my plan was to save money, but like most fishermen, wine, women and song got in the way, and I never saved a penny!

“Fishermen on the Grimsby and Hull boats were known as the ‘three-day millionaires’. We would go to sea for three weeks, come back and spend the lot in three days, then go back to sea to get more money, and start all over again. We were millionaires of sorts, and when you needed to get to the pub 100 yards down the road, you didn’t walk, you got a taxi, because walking was a waste of drinking time! Fishing from Grimsby was the right job for me. Being a youngster working on the Grimsby boats meant you didn’t have to be on a half-share; if you did a man’s job, you were paid a man’s wage.

“I started off with Northern Trawlers. I then went with British United Trawlers; I spent a while with the Ross fleet, and then went back to Northern Trawlers. I then did a few trips with smaller northern firms, and stayed in Grimsby.

“Built as a trawler in Germany in 1936, the sidewinder Northern Gem was the first boat I ever sailed on.

“The Northern Gem arrived at Grimsby at the time of reparation after the First World War. In truth, the Germans never paid a penny in cash in compensation for the war, but German goods were taken by the British government as frozen credits, and they took away 36 German boats, of which the Northern Gem was one. The 36 or so boats went mainly to Hull, Grimsby and Fleetwood.

“When I started on the Northern Gem, I saw boltholes on the deck where the British navy had mounted guns, because it was used in the Second World War as a convoy escort vessel. Its most famous Arctic convoy while escorting Russian ships was PQ17, one where many vessels were destroyed by German U-boats off Murmansk.

“After the Northern Gem, I went to Iceland, but because I couldn’t get on with the skipper, I did just one trip and then came back to Grimsby and continued as a trawlerman. I was at sea in 1968 when three boats were lost, the Ross Cleveland, the St Romanus and the Kingston Peridot, and we were the last to see the Kingston Peridot before it was lost.

“I remember hearing that Phil Gay, skipper of the Ross Cleveland, said, ‘Give my love, and the crew’s love, to the wives and families.’

“It was all a dreadful loss. I believe that a few days before Phil went on that trip, he attended an interview to become a prison officer, and was offered the job. I will never forget Phil Gay, or anyone else who never came back from that triple loss. Only one fisherman survived from the Ross Cleveland, Harry Eddom, and to reach safety he climbed a cliff in Iceland, one that was thought unclimbable even in the summer. It was 300ft high, but he climbed it in the winter, and sheltered behind a farmer’s hedge until he was found. Harry Eddom became a hero in Iceland.

The tiny ‘giant’ J-Anne (centre) would be the chariot of Grimmy Mike Mahon’s fight to help take Britain out of the EU.

“But let’s change the subject; it’s too upsetting for me. The loss of the three boats was awful – unthinkable nowadays, but it was a very long time ago.

“There was always banter and rivalry between Grimsby fishermen and Hull fishermen; sometimes things between a Grimmy and a Yorkie were humorous, sometimes not. The life of a Grimmy on a Hull boat became a dog’s life, and the same in reverse.

“With Britain versus Iceland, I could see that the Cod Wars were damaging our industry; and when I saw the oil industry develop in the North Sea, I could see nothing ahead but a complete wipe-out for commercial fishing in the North Sea. So, in the end, I moved from Grimsby to Cornwall, and it’s you lot at Fishing News that the MMO should blame!

“I had done my research on the future fishing potential for me in the South West, and I saw an advert in Fishing News for a skipper in Cornwall at St Mawes. I got the berth, but it quickly became a disaster; the boat’s owner wouldn’t give any backup to the boat. We couldn’t even get a shackle, and were given old shackles by the men servicing the nearby moorings. I lived aboard the boat for about four months. Being the skipper just wasn’t working, so I went back to Grimsby. However, shortly after that I came back to Cornwall, to Newlyn, to join a W Stevenson & Sons beamer, Algrie.

“WS&S had just bought the Algrie, and I was OK aboard there. David Hooper was skipper, and David Stevens was mate. WS&S then bought the ‘AA’ – Aaltje Adrianntje – and David Hooper left the Algrie to skipper the AA. David Stevens took over the Algrie, and I became its mate.

“I didn’t get on with beam-trawling, and after a while I met David Stevens’ younger brother, Peter Stevens, and Bobby Sowden, and in the end we all went stern-trawling single-handed and worked a buddy system, fishing fairly close together for safety.

“After a disastrous short time with my first stern-trawler, an old 50ft French boat called Joal, I ended up buying Betty G, a 41ft steel boat. Although it was for single-handed trawling, for a time I had crewmen, like Derrick Round, and for quite a while one nicknamed ‘Pickles’ – but I had to sort of sack him every three months or so for him to settle down! I still don’t know Pickles’ real name – but he was always on time, and never let me down. He was superb, a brilliant crewman, and I never lost one hour of sea time because of him. But he used to get so wound up that every three months I would tell him to go home and have a week’s holiday.

“Pickles was a grafter, no doubt about that, always reliable – but like many crewmen he might turn up quite drunk – I suppose that’s a nice way of putting it. But I would never allow any crew to bring alcohol aboard my boat, so only one thing could happen. Eventually they sobered up!

“In the end, I decided to go single-handed all the time. I always came back to port each night. But I didn’t go home; I slept on the boat, and because the fishing was good, I once did a stint of 28 days before going home. I used to work that system almost all of the time, and fish until the weather stopped me. I used to live on my nerves, and on my luck some of the time.

“Even with the J-Anne, I did extended trips, but came back to port almost every night and slept on the boat. I would keep on fishing until I had enough fish to land, and only then went home to Praa Sands.

“My spell with Joal was short. The boat kept going wrong, it was a disaster, the engine was knackered – so I made it known that I might sell it if the price was right. A chap with an Irish accent kept getting in touch, and unknown to me that person was Joe O’Connor, the Anglo Spanish flagship agent in Plymouth.

“He made several offers, but in the end, a chap called Peter phoned me and agreed a better price, and I decided to go ahead. He paid me a 10% deposit, saying I would get the rest when I delivered the boat to Plymouth, which I did. I later found out that the sale was really to Joe O’Connor.

“I don’t care what people say about the flagship frontmen like Joe O’Connor; at that time, the government allowed them to do it. And say what you like about me selling Joal to Joe O’Connor – I had no idea I was doing so, but although I disagreed with flagships, I later found out that Joe O’Connor brought work to so many fishermen who thought that after the Cod Wars, their time at sea was over.

Single-handed trawlers from Newlyn often worked in a buddy system for safety, fishing fairly close together.

“I had sold Joal and its licence. Licences were relatively new, and changed hands fairly cheaply. Joe said he would give me an extra £500 to help me transfer the licence, and I took it and went to the Plymouth MAFF office, where district inspector Colin George warned me that I was acting as a frontman for the flagships, and he would only reluctantly do the transfer. I told him that he had to do it, and that it wasn’t me helping Joe O’Conner to act against the government’s wishes, but that the government was caught with its pants down, allowing people like Joe to do what they were doing.

“It was that deal that started my fight with UK and EU fisheries management. Afterwards, I asked Fishing News to reveal that the Anglo Spanish fleet was growing at a frightening pace, and to report on the government’s shortfalls in stopping it. MAFF had simply left the doors wide open for the flagship fleet to flourish. The UK government had impoverished the UK fishing industry, and had forced many owners to sell their licences.

“And before anyone criticises the flagship owners, remember those British fishermen who were suffering real poverty after the Cod Wars. Who was going to employ those men? Ports like Hull, Grimsby, Fleetwood and Aberdeen were in tatters. But because flagships at that stage had to have 75% British crews, people like Joe O’Connor gave those men a job, gave them a future, gave them hope. Like it or not, it was only the flagships that brought fishing work back to our Humber men. The rest of our fishing industry was crumbling too, and the government couldn’t care less.

“I don’t know whether Fishing News did report on flagship businesses flourishing, but that was the point at which the politics of fishing became of great interest to me.

“The government had washed its hands of the British fishing industry. Men from the Cod Wars were desperate for work, one being Ernie Suddaby, skipper of the tragically lost Hull freezer trawler, the Gaul. Ernie had had a trip off, and was the only person from the Gaul left alive. I was skippering the scalloper Gratitude from Mevagissey, and Ernie came as my crewman. What does it take for a government to understand the mess it has put the fishing industry in? Why, in this country in around 1987, did the skipper of one of Hull’s top freezer trawlers end up as a crewman in Cornwall, working on a scalloper? Ernie wasn’t the only big-boat skipper to be left scratching for work, and only flagships provided work for such men. I believe Ernie skippered one of Joe O’Connor’s freezer trawlers, Fishing Explorer, destined for the Falkland Islands.

“The ineptitude of the British government made me open my big mouth and broadcast facts about the mess we were left in – it gave me the impetus to shout about the British government actions that, in a very short time, had ruined a once-proud British fishing industry. And I will still shout, until we regain control of our waters.”