The eighth article in the series by Hull skipper William Oliver, first published in 1953/4. Photographs courtesy of Alec Gill

In August 1915, during the First World War, I was skipper of a Grimsby trawler, the Tokyo GY 167. During a routine trip, we were suddenly recalled from sea, ordered to fill up with coal, water and provisions, and proceed to Malta.

There were very few signs of war at that time in Malta. Apart from the hospital ships arriving with the wounded from the Dardanelles campaign, everything seemed normal.

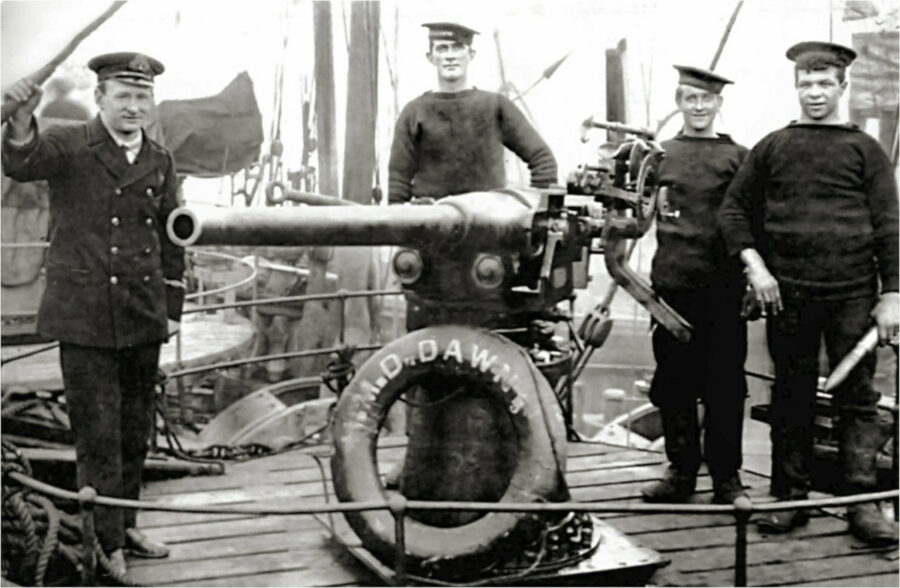

Skipper Edward Spencer Rilatt the third (left) with gun crew on the HMD Dawn. Edward Rilatt was from a well-known Hull fishing family and was one of many recruited into the RNR during the First World War. He was nicknamed ‘Mad’ because of his explosive temper – towards both the Germans and Royal Navy officers!

We kept hearing of losses in the fishing industry at home, both by mines and submarines, and fishing was very much disorganised. Skipper W Grantham had made the first £2,000 haul. Catches were increasing in value with every month that passed, but more and more vessels and personnel were being enrolled by the Admiralty. Very soon, there was nothing left of our fleets but the oldest ships – except for the Conan Doyle and the Admiral Craddock, which were fairly modern vessels. These two remained fishing until the end. I would also mention Cadet, which was built in 1915.

Zeppelin raids were fairly frequent by now, and Hull was particularly singled out. We were informed by our letters from home that air-raid warnings were quite common.

In February 1916, our eighth child was born. Three weeks afterwards, my wife was out in the snow-covered street with all the children at midnight during a Zeppelin attack. The airship hovered over the defenceless city for more than an hour.

I was very upset when I heard the news in Malta, as we were in safety and living in comparative luxury. So I wrote to my wife and suggested tentatively that she might like to come out to Malta with the children. To my surprise, she jumped at the chance and, after a long and arduous journey, arrived early in May. The coming of the family brought many problems for me – mainly financial ones – but we soon settled down for two of the happiest years of my life.

Meanwhile, things had been happening at Malta. On 26 April, 1916, we were ordered out to sweep the main channel one hour earlier than usual. Our senior officer was in harbour as his trawler was undergoing refit and boiler cleaning, and I, as senior skipper of the flotilla, was in charge.

As soon as we connected sweep, I saw a large battleship on the horizon making for Valetta harbour. I knew then why we had been ordered out earlier than usual. We carried on sweeping out, and I was keeping my glasses on the battleship when I saw a large cloud of smoke mushroom from her, followed by an explosion. Shortly afterwards, there was yet another cloud of smoke and another explosion.

I immediately slipped sweep and proceeded at full speed towards her, and ordered the rest of the flotilla to do the same. It was HMS Russell, flagship of Admiral Freemantle. She had struck two mines in quick succession, and was badly holed and sinking, with the crew already abandoning ship.

King George V and Queen Mary inspect a minesweeping crew during the First World War. (Photo courtesy My Learning)

Our section of minesweepers rescued 675 officers and men in 20 minutes, before Russell turned completely over and sank. We managed to save about 200, including her captain, Captain Bowden-Smith RN, the admiral’s flag-lieutenant, the major of marines, the chaplain, and many others. Six ratings died on our deck from severe burns before we got into harbour.

After this, mines were discovered every day for some time, and we lost four more ships – a patrol yacht, a fleet sloop and two trawlers.

In June 1916, I was transferred from minesweeping and placed in charge of the maintenance of the anti-submarine defences around Malta. It was a semi-dockyard appointment, and I had regular hours, being in harbour from Friday noon until Monday morning every week. So I took no further part in the active prosecution of the war.

Every six months, I received a letter from Mr McCann in Hull, giving me all the latest information about fishing activities. In 1918, my wife’s health started to deteriorate. She was advised that the climate of Malta was unsuitable for her and she ought to return to England as soon as possible.

The war had dragged on for four years, and conditions were vastly different in 1918 to what they had been in 1916. Submarine activity had become very marked in the Mediterranean, and all mail boats to the island had ceased. In place of the P&O, a naval vessel ran between Malta and Taranto in Italy, and all passengers and mails were dispatched by that route.

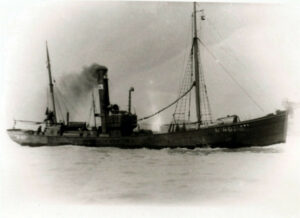

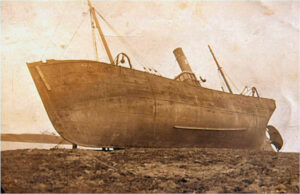

The Hull trawler/minesweeper Owl H 801 in the river Humber…

It took weeks of negotiation to arrange my family’s passage home, but at last permission was granted, and my wife and family left Malta in September 1918, going by way of Taranto, Rome, Paris, Le Havre and Southampton, having done the double journey in wartime. Whatever war medals I afterwards received for my services were better earned by Mrs Oliver than by me.

One Monday morning, 11 November, 1918, at 11am, I was ashore at Floriana on business and called in for a quick one at a bar. Suddenly there was a loud clanging of bells, and hundreds of Maltese were excitedly running along the streets to church, shouting “Spitehia guerre!”, “Spitehia guerre!” – “The war is over!” Yet, for all that I felt, and like so many others, it was not easy to express more than tired relief. Except that at last I was going home.

I left Malta in December, and after calling at Gibraltar and Lisbon, arrived at Portland on 1 January, 1919, en route for Grimsby. Strange to say, I have forgotten the name of the trawler I brought home. In due course I was demobilised, and in February went to Mr McCann’s office to report, once again, my readiness for fishing.

Trawlers and trawlermen well suited to minesweeping

In 1907, Admiral Lord Charles Beresford was commander-in-chief of the home fleet. After a visit to ports on the east coast of England, he was the first to recommend the use of trawlers for minesweeping duties.

He wrote: “Our fishing fleets, in war, will be rendered inactive and will, in consequence, be available for war service. Fishermen, by virtue of their calling, are adept in the handling and towing of wires and trawls, more so than are naval ratings. Small naval vessels, if used in minesweeping, will be used at the expense of other urgent war requirements.”

… and grounded on a reef at an unknown location, in her minesweeping role, after a terrible storm on the night of 4 or 5 February, 1915. She was refloated, continued fishing after the war, and was sold to Fleetwood owners in 1937. She was scrapped in 1956.

Admiral Lord Beresford’s foresight eventually led to the formation of the Royal Naval Reserve (Trawler Section) – the RNR(T).

This brought a new rank of ‘Skipper’ RNR into the Navy List, and the first officer enrolled at Aberdeen on 3 February, 1911. When the First World War started in August 1914, a total of 109 skippers had joined, and 315 more volunteered by the end of the first week of October. By the end of 1915, the Minesweeping Service employed 7,888 officers and men.

Within the first week of the war, 94 trawlers were allocated for minesweeping duties and dispersed to priority areas including Cromarty, the Firth of Forth, the Tyne, the Humber, Harwich, Sheerness, Dover, Portsmouth, Portland and Plymouth. The groups were commanded by naval officers, some from the retired list, who had received a brief training in minesweeping.

The trawlers were fitted out with heavy guns, machine guns and depth charges. By the end of 1916, the Navy had requisitioned so many trawlers, and the war had had such an impact on shipping, that the supply of fish to the UK was severely limited.

New trawlers were also built. Between 1914 and 1918, 371 trawlers were built in the Humber shipyards, and almost all of them were taken up by the Navy and used as minesweepers, submarine spotters and coastal patrol boats.

Men were asked to volunteer for the new service, and many did so. The Humber area provided over 880 vessels and 9,000 men from the fishing industry to support the war effort.

At the end of the First World War, the Admiralty appointed an International Mine Clearance Committee, on which 26 countries were represented. The Supreme War Council allotted each power an area to clear, the largest falling to Britain. Some 40,000 square miles of sea needed clearing. In February 1919, a Mine Clearance Service was formed, with special rates of pay and conditions of service. Members of the service wore a specific metal cuff badge and cap tally. By the end of 1919, over 23,000 Allied and 70 German mines had been swept, with the loss of half a dozen minesweepers. The Mine Clearance Service was disbanded in 1920.