The Wash cockle fishery opened on Monday, 17 June with a TAC for this year in two parts: 4,004t from what, until recently, was the full extent of the regulated fishery, and a further 323t from a new area now part of it, reports John Worrall

And thereby hangs a tale.

It goes back to 1066 and all that. When William conquered, he dished out parts of his new domain to the barons who had fought for him, and who had to be kept sweet because he had conquered with a surprisingly small force – possibly only 10,000 men – and he needed them to help keep a lid on the country. By the time he died in 1087, his family owned about 20% of England, the top 10 nobles a quarter, and the church (as insurance for the afterlife) another quarter.

The hand-worked fishery starts on a falling tide, with a bit of prop-washing to reveal the cockles…

On the east side of the Wash, a chunk of land and foreshore came into the hands of the Le Strange family, with whom much of it has remained ever since, and which, until last year, included something approaching 10% of the Wash fishing ground. And that ground was particularly good for cockles.

But when fishery regulation began to creep in, starting back in the 19th century, that patch was – and has remained – private ground, and therefore unregulated. The cockles therein were part of the same Wash biomass – the spat could have come from anywhere in that swirling embayment – but the Wash Fishery Order 1992 (WFO), the current regulatory legislation, did not, and does not, apply, and the few boats permitted to fish there by the estate were not bound by WFO rules.

… before the boats settle in the selected area and the crew start hand-raking on the flats.

And so, for instance, when, in 2008, cockle dredging ceased in the regulated area, and the WFO fishery changed to hand-working, the private fishery carried on dredging.

And all of that was fine as far as it went. Anachronistic it may have been, and so it remains, but there was a legal basis for it.

The problem was that the actual boundaries of the private fishery had never been precisely defined. There were various notions, ranging from ground that could be fished without a boat – down to extreme low water of a spring tide – to the apocryphal ‘as far as a man can ride a horse and throw a spear’ which, on the vast flat sands of the Wash, and depending on the tide and the beach profile at the time, could be a very long way indeed.

Hand-worked cockles come up nice and clean.

But the absence of spears in the foreshore, and the generally mobile nature of the Wash banks, left its demarcation open to wide interpretation, particularly when sandbanks became attached to the foreshore through the silting of intervening creeks.

And it was around that latter aspect that the debate gradually crystallised, because two sandbanks had actually gone through that process: the Stubborn Sands off Heacham, which originally ran parallel to the foreshore, before becoming attached sometime in the 18th century, and, more significantly, the adjacent Ferrier Sand to the south, which stretches much further out and became attached only about 50 years ago.

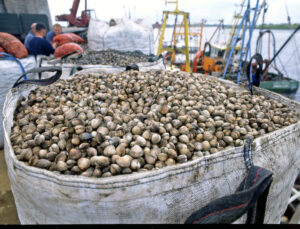

Cockles are a major part of the Wash fishery.

The original delineation for the WFO did not include the Ferrier, leaving it to be claimed by the estate, and that increasingly was the root of resentment among excluded fishermen, because the low water mark of the Ferrier is more than two miles out to sea.

Eventually the courts became involved, starting in the 1970s, but things cut to the chase in 2007, when 13 boats from King’s Lynn, 10 of them from Lynn Shellfish, steamed in and dredged cockles, to see what the estate would do about it.

The upshot was that last year, the whole thing finished up in the Supreme Court, where five law lords ruled that it was one thing for ownership to be enlarged through gradual accretion to a shoreline – an accepted principle backed by precedent – but it was quite another for ownership to be claimed when silting suddenly filled an intervening creek.

Cockle dredging in the regulated fishery stopped after 2008.

And so it was that on 27 July, 2018, a judgement was handed down drawing a line in the sand and mud, which apportioned a sizeable chunk of ground, formerly part of the private fishery, to the regulated fishery. It vindicated Lynn Shellfish, which had forced the issue, but straightaway required rapid response by Eastern IFCA to bring in appropriate management measures on its new patch.

And that wasn’t as straightforward as it might sound.

The WFO boundary couldn’t simply be changed, because DEFRA and legal opinion said that that would require amendment of the WFO (itself already under long-term review in any case). That would be a lengthy process, with all the necessary consultations. So Eastern IFCA had to introduce the Wash Emergency Byelaw by way of a cover note.

And like all cover notes, it was temporary, because under the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 (MCAA), emergency byelaws expire after 12 months, and this one will expire on 26 July, 2019.

It will be replaced by the Wash Restricted Area Byelaw 2019, which will replicate the powers of the WFO as far as possible. It will also include flexible management arrangements to allow quicker reaction when needed, such as to the threat of loss of stocks through ridging out or atypical mortality, when the fishery might be extended or reopened in order for stock to be caught before it is lost.

As it happens, the consultation process on the new byelaw will itself not be complete by late July, in which case, the MCAA does allow for a six-month extension if there is good reason.

And since the Wash, as part of the Wash and North Norfolk Coast Special Area of Conservation and Special Protection Area, has just about every environmental designation going, and cover therefore needs to stay in place, there is good reason.

But the net result is that the majority of Wash entitlement holders will have a new patch of cockle ground to work with. This year’s cockle survey showed the original regulated fishery area had 12,011t of adult cockles above 14mm, and 6,654t of juveniles, roughly two-thirds of the juveniles being from the 2018 year-0 cohort, which is reasonably healthy.

See any knights on horses lobbing spears? The Ferrier Sand off Snettisham, no longer part of the private fishery…

In addition, the new patch had a further 969t of adults and 174t of juveniles.

On the usual thirds shares – for the birds, for regeneration and for the industry – the new patch therefore offers that TAC of 323t, worth over £1,100/t on last year’s prices, which – if they are not too thinly spread for hand-working – is a bonus.

But densities are important. Adult stocks are widely spread around the Wash, and while the survey showed some high-density patches for hand-working to target, fishing out the full TAC is expected to be difficult.

And the spread – thick or thin – does again raise the question of dredging, because dredging can work with lower densities than hand-working.

Dredging began in the Wash back in 1986, but it was under light regulation, and its greater efficiency saw Wash stocks quickly fall below levels at which those still hand-working could work economically. Peaks and troughs followed, and led to the fishery being totally closed in 1997. A TAC was introduced for the first time when the fishery reopened in 1998.

But then, each TAC was taken up quickly – over just three weeks in 2004 – as boats took their daily 2t allowance until the TAC was fished out, and bad luck on anyone who had a breakdown. So the industry view, while not unanimous, moved in favour of hand-working, because the smallest boats couldn’t carry dredge kit anyway, even if they could afford it.

The last dredge fishery on the regulated beds was that in 2008, and in 2016, the authority made hand-working the default method.

… and the Stubborn Sands off Heacham, which still are.

Eastern IFCA recently carried out a hydraulic suction dredging impact assessment to look at dredging again, and it reported to the full authority in May. The first issue, in these times of much tighter environmental protection, is that a dredge fishery would need evidence that it wouldn’t damage the site’s designated conservation features, and that would be far from certain.

There is no direct evidence of significant changes to the benthic following previous dredge fisheries, but with the last one over a decade ago now, the damage could be masked or repaired.

Either way, the precautionary principle comes into it, more particularly for repeated dredging over several years, which was what used to happen. It might conceivably pass a habitats regulations assessment in some places, but a lot of comparative monitoring would be needed before it did so, more particularly if dredging were to resume alongside hand-working, which has happened in the past – and it all looks unlikely.

Add in that continued majority resistance among the industry, and dredge gear probably won’t be getting wet in the Wash for the foreseeable future.