Passion and vigilance, allied to a lifetime’s experience and local knowledge of tidal trigonometry, delivers a return

The salmon drift-net fishery has sustained fishermen and their families along the coast of northeast England for generations. Whitby skipper Martin Hopper is one of 11 netsmen, fishing over 100 miles apart, who are fighting for their future, as anglers and riparian owners continue to apply pressure on ministers to stop the traditional fishery. David Linkie reports

The family traditions that are strongly associated with the salmon drift-net fishery were immediately underlined when skipper Martin Hopper, who has been a licensee for 30 years, stepped onboard Courage accompanied by his son Shaun.

After the all-important flasks and pack were securely stored under the aft thwart, Martin Hopper carried out his customary checks, before bringing the Ford 4D engine to life and giving it a few minutes to warm through, during which time he contacted Whitby bridge on the VHF to request the 6.30am bridge. At the peak of spring tides, the plan of action was to be shot in time for the highwater slack, some two hours later, so a considerably later than usual start was possible.

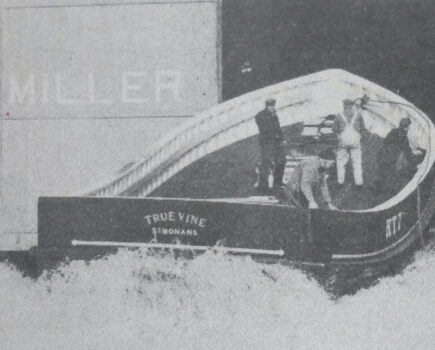

Courage returning to her pontoon berth 11 hours after…

With the remnants of a fairly heavy ground swell still running on Sandsend beach, conditions were unsuitable for J-netters, so Courage, Whitby’s solitary remaining drift-net coble, would be well and truly on her own for the day, with her closest companion some 50 miles further north off Sunderland.

When the eastern half of Whitby’s distinctive swing bridge opened, Courage passed through before going alongside the fishmarket to pick up a couple of baskets of ice, which would hopefully be put to good use later in the day.

Five minutes later, Courage started to lift to the

decaying swell on passing through the pier ends, before Martin put the tiller over to port at the start of a 10-mile steam south towards Ravenscar.

Coming after weeks of flat calm seas, constant sunshine and unusually high temperatures – not an ideal combination for drift-netting, as below-average catch returns conclusively proved – the return of more usual conditions, including a rolling sea and grey skies, were welcomed – unlike the strong tide, which meant that continual effort lay ahead.

The extent to which potting effort continues to increase along the Yorkshire coast was made immediately apparent by countless pot dahns, some of which were all but submerged, as Courage, running before the motion and a whistling flood, quickly passed under Whitby Highlight lighthouse.

… passing through Whitby’s swing bridge

Towards the end of the previous week, when neap tides prevailed, Martin Hopper had successfully fished under the cliffs at Maw Wyke, four miles east of Whitby, where a small area of soft bottom, which meant no pot end for some 400m, provided sufficient seaway to work a drift net. However, with spring tides ruling out this preferred shot, as the net would have had to be hauled almost as soon as it was in the water, Courage continued to head on towards Ravenscar, on the southern side of Robin Hood’s Bay.

An hour after Courage left Whitby pier ends astern, and going to a more or less dictated starting position tight to an uptide pot dahn, Martin turned the coble’s head out to sea as 550m of drift net was cleanly shot off the deck over the starboard gunwale. Lying at the off-end and looking back along the line of white headline floats, the small scale of Courage’s net compared to the open sea was immediately put into perspective by the dramatic towering cliff.

The ever-present threat of a seal taking a fish from the net, often within a minute of it striking, requires the crew to keep a vigilant eye along the net at all times for any signs of activity. With no sign of a fish hitting the upper section of the net after 15 minutes, Martin took Courage slowly along the net, when the hoped-for telltale sign of a fish lower down the net, in the form of a slightly dipping float, did not materialise.

On reaching the inside end of the net, the boat hook was made ready, at the same time as the hydraulics for the Rapp Hydema Piccolo hauler were clutched in. Although only in the water for 20 minutes, the off-end of the net, which continued to be subject to the full weight of the flood, which was now starting to ease closer in, had been pulled around 90° and was lying down through the tide, parallel to the shore.

After a non-productive first haul, Martin took Courage closer in to the foot of the cliffs, looking to gain maximum benefit from the highwater slack, which would initiate along the shore before moving into the sea.

With Martin constantly checking Courage’s heading on the boxed compass, his constant companion aft, the net was shot for a second time. On running along the net five minutes later, the first fish of the morning was spotted halfway in, about a dozen meshes down from the headline. After coming gently astern, the landing net was used to safely bring a 9lb salmon aboard.

Shooting the net away for the first time…

Continuing to look along the net yielded a second fish in the form of a well-formed grilse (a young salmon less than 3.63kg), and Courage was up and running.

As the offside end again trailed away south with the last of the flood, Shaun had started to flake handfuls of headline down onto the deck boards, when the smooth routine of hauling ceased for a minute as a second similar-sized salmon, meshed near the lead line, was carefully lifted over the gunwale.

Shot in a similar area and manner to the second, the third shot yielded another two fish. One of these was thought to have been seen oversetting some 20 yards from the net while Courage was lying at the inside end for a couple of minutes, while Martin and Shaun tagged and recorded the first fish of the day.

Although the only predictable thing about netting is its unpredictability, the highwater slack was showing encouraging initial signs of delivering. These continued on the next shot, when on the first check of the net, a telltale heavy flat not only provided indication of a grilse, but also a second bigger fish deeper down. With Courage threatening to blow across the gear, this had to be left for a few minutes, before it was successfully taken aboard when the net was immediately hauled, along with another two fish.

… and hauling after 20 minutes for nothing.

With the first signs of ebb beginning to appear inshore, with slightly coloured water displacing the clearer flood, Martin subtly brought a lifetime’s experience into play by positioning the net slightly further out on the next two shots, in order to repeatedly straddle the tideline, which fish have a tendency to follow.

At the same time as gradually moving further offshore, the angle that the net was shot, relative to the shore, was carefully judged and constantly adjusted in respect of rapidly changing tidal patterns, in an attempt to extend the time the net would fish effectively by a few minutes.

In less than 15 minutes, giving just enough time for a quick look along the net, which yielded the third grilse of the day, it was hauled back onboard as it quickly pulled round.

As the clearer water continued to move eastwards, Courage tracked it offshore as Martin endeavoured to increase the count of salmon and grilse which, approaching midday, stood at three and seven respectively.

Looking along the net shortly after it was shot for the second time…

With ebb now running fiercely, and the net moving quickly northwards towards pot dahns, it was taken back onboard twice in little more than 30 minutes, during which time another two grilse were securely lifted aboard when hauling.

Rather than face the prospect of doing similarly for the next three hours, Martin opted for plan B, which was to move closer to the shore again, where it was hoped the tide would not be quite as strong, and would continue to ease as low-water slack neared.

This course of action meant returning to the coloured water, and that if any fish were netted, they were more likely to be sea trout than salmon or grilse.

Therefore it was slightly surprising that 10 minutes later, the first look along the net resulted in a grilse being taken aboard, followed by a good-sized sea trout some 25 floats on. As the net set northwards, the 400yd gap between pot dahns reduced rapidly, so it was hauled back onboard, together with two more sea trout, lying well down towards the footrope.

The next two shots followed a similar pattern and yielded another three trout, all around the 5-6lb mark. This good class of fish highlighted the selective nature of all forms of gill-netting, in which the size of fish caught is determined by mesh size. Looking to secure maximum financial benefit for the fish caught, Martin Hopper uses 4¾in mesh, which is generally more suited to taking larger fish. Although this means that considerable numbers of smaller trout and even grilse will pass through the net, the benefits of this policy are clear to see, in that one double-figure salmon considerably outweighs a dozen small sea trout.

… resulted in the first fish of the day being spotted…

The 200yd sheets of 4¾in x 60 mesh-deep 0.65mm super-soft monofilament netting are taken in by the half during rigging, when every three meshes are hung at 7in intervals on the headline. The spacing is increased to 8in on the footrope (no. 2 leadline), to give the optimum amount of slack and allow the netting to lift when a fish strikes. This combination of mesh size and rigging method allows 4lb sea trout to be retained as well as 20lb-plus salmon.

Apart from a young pup, clearly still learning the ropes and honing the skills associated with mauling migratory fish in a net, the day had been relatively seal-free until now, although this was about to change.

Another reason why the highwater slack is generally viewed as providing more favourable conditions is that adult seals have a tendency to swim ashore and lie on scar ends for a few hours. The downside of this is that as the tide starts to turn, well-rested seals take this as a signal to return to the water, and almost inevitably start feeding. In the late morning, over 100 seals were basking in the sun on the rocks, and several groups of tourists had walked down Ravenscar cliffs to view them close-up.

As the first flush of flood materialised, the number of seals lying on the rocks quickly diminished, and it was not long before five adults started to patrol Courage’s net. How many migratory fish seals kill in a year is unknown, but given the huge numbers of seals along the coast of northeast England, allied to their well-documented dietary preference for salmon, the number of fish lost to these predators probably runs to thousands.

Shaun washing a beautifully conditioned glistening salmon.

Although constantly watching the net for any telltale splash of fish playing up near the headline, when Courage can be there within two to three minutes to take the fish out, Martin regularly comes second in a two-horse race, to be faced with a seal mauling a fish. Known losses in any one week regularly run into double figures, and those are only the ones seen in the top part of the net.

For whatever reason, Courage’s net, as well as the mouths of the seals on sentry patrol, remained empty on the next haul. Rather than put in further effort for no return, and with highwater not an option as it was not until after the daily close time, the net was kept aboard after being hauled for the 14th time in eight hours.

Finely tuned to local conditions, netsmen like Martin share the common characteristic of readily identifying when to fish, and when attempting to do so would only be riddling water. Although restricted to 65 days a year and 76 hours a week, netsmen frequently opt for a combination of late starts (as was the case on this day), early finishes, and returning to harbour for a few hours in the middle of the day, rather than attempting to maximise the time they can fish, as some observers imply.

Under the terms of the three-month licence issued by the Environment Agency, salmon drift nets can be fished from 6am to 8pm on a Monday, from 4am to 8pm on a Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday, and from 4am to 6pm on a Friday. Previously, licence holders were able to fish from 6am on a Monday morning through to 12pm on a Saturday.

The length of the season has been similarly reduced, with the traditional opening date of 28 March being moved back to 1 June.

Pride in their work – Shaun holds a superbly conditioned salmon.

From a purely personal perspective, being given an opportunity to spend time at sea with netsmen is a privilege. Gaining an insight into their ways of reading local conditions, together with their passion and commitment to a form of fishing they have devoted their lives to and supported their families with, is a unique opportunity.

From the moment Courage passed through Whitby pier ends, until steaming home to Whitby, when Fishing News was entrusted with the watch, Martin Hopper’s hand never left the tiller, apart from a few brief minutes to fill out the daily catch sheet as soon as fish were caught and tagged. Half-cups of coffee and sandwiches were quickly taken while remaining at the helm, constantly on watch while monitoring the position of the net in relation to pot dahns and passing yachts, which frequently need to be diverted clear of the gear.

The concentration and skill required to keep an open boat in position, when hauling and looking along a net in close proximity to it, cannot be overstated. While many skippers rightly benefit from the advantages associated with autopilots, satellite compasses, radars, sonars, and the like, such equipment has no place on traditional netting cobles, where a skipper and his crew rely on their lifetime’s experience, together with instinct and constant awareness.

Netting the last salmon of the day over the port side…

With Courage stemming the full weight of the flood, the steam north to Whitby took 50% longer than it had done 11 hours earlier. Shortly before 5.30pm, Martin took Courage alongside the fishmarket quay to land the day’s catch. Consisting of four salmon (21.2kg), 14 grilse (37.9kg) and seven sea trout (17.1kg), the fish – which were as stiff as boards and in superb condition, having been boxed and lightly iced as soon as they came aboard – were weighed and laid out, ready for auction the following morning.

Having frequently landed less since the 2018 season started, as well as throughout his long netting career, Martin Hopper was quietly satisfied with the return, in much the same way as he would have been with fewer or more fish. Stoicism has long been of paramount importance to netsmen, who are accustomed to looking forward to the next day, in the knowledge that long-term security and sustainability are of greater importance than short-term gain.

Continued below…