Three weeks at sea, three days ashore: the work pattern of Hull trawlermen put unique – and often hidden – pressures on fishing families

By Alec Gill

Easter week was always a high point in the fishing year in Hull’s trawling heyday, with high-grossing landings due to the longstanding tradition of eating fish on Good Friday.

Good settlings after a catch had been sold meant that the trawlermen, ashore after a three- week trip to the Arctic grounds, would have lots of money to spend – though there was always the risk of ‘landing in debt’, a phrase that may well have been coined within the fishing industry.

With only 72 hours in port, trawlermen gained the nickname ‘three-day millionaires’. But while the younger men had little to think of beyond enjoying themselves during their brief time ashore, the working pattern of 21 days away with only three days at home put a powerful strain on the lives of married crewmen and their families.

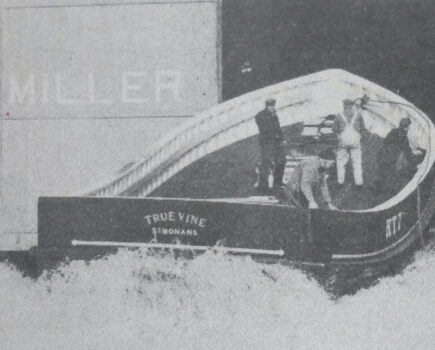

It was certainly a treat for school-age youngsters to go down to St Andrew’s Fish Dock to see their dad’s trawler returning home, and be lifted aboard over the port side of the ship. The kids sometimes had free run of the trawler. If their dad was an engineer, they were taken down to the noisy engineroom to see

the pistons pumping. Some got up to the wheelhouse and looked through the skipper’s binoculars at ships passing on the busy Humber.

One lady told me that, while at secondary modern school, she would take her best friend along to see her dad’s ship return. Once onboard, they had a law-breaking routine. Down in her dad’s berth he had stashed away a good store of duty-free, bonded tobacco. The girls both secretly stuffed the packets into their navy blue bloomers.

When Customs and Excise officers came aboard looking for smuggled cigarettes and tobacco, the two girls never got searched. After the ship was secured, her dad’s regular taxi driver was waiting on the dockside. They all clambered inside, and at home the ‘booty’ was unpacked. The tobacco was given to friends and family.

One trawlerman’s son told me that when his dad came home: “It was like Father Christmas coming every three weeks.” Some dads felt guilty for being away – especially if they had missed a birthday, school prizegiving or the like – and tried to compensate by bringing home lavish presents.

It was not easy being a fisherman’s wife. Whilst her husband was at sea, she was ‘mother and father both’ to their children, and had to find ways of coping with his long spells away. Then, suddenly, he was back, and her domestic routine was turned upside down. Life then revolved around what he wanted to do.

There is a crude joke about what happened when a husband arrived home: “What was the second thing a trawlerman did when he met his wife?” Answer: “Take the seabag off his shoulder!”

The fisherman’s first day home usually involved having a taxi on hand to take his wife to the Tivoli to see a show, then around the corner to the Gainsboro Fish and Chip Restaurant for a good meal. After that, it was a taxi to a pub on Hessle Road – probably Rayner’s, the ‘fishermen’s pub’ – to meet up with other crewmen and their wives until closing time.

Finally, everyone would pool money into what was called ‘a tarpaulin muster’. Bottles of beer were bought, and everyone piled into taxis and headed to someone’s house for an all-night party.

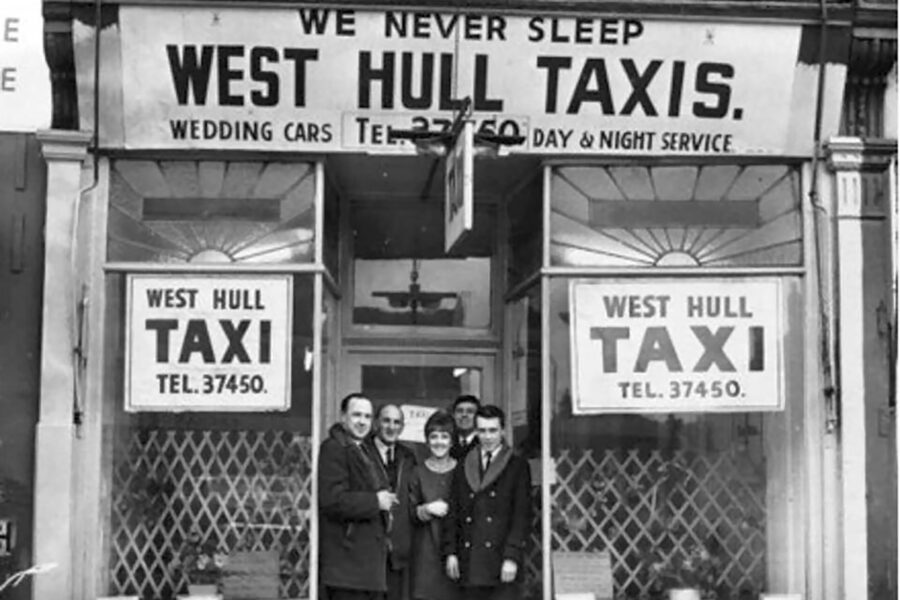

Hessle Road taxi firms did great business with the Hull trawlermen. One firm’s advertising slogan was: ‘All Tides Attended’. The drivers sometimes carried the men’s seabag on and off the ship. There was a superstition that it was bad luck if he carried it himself.

Beneath the hurly-burly, fun and laughter, however, there was often an undercurrent of unspoken anxiety for both husband and wife. During their limited time together, neither wanted to spoil things

by telling the other about their worries.

For example, the wife did not feel it necessary to mention the children’s illnesses, quarrels with neighbours, their son being bullied at school, her own aches and pains, struggling to afford school uniforms, or how to settle the corner-shop bill for items bought on tick. Even an early-stage miscarriage might never be talked about.

Equally, he did not want to offload his worries on her. What was the point of talking about the dangers endured during the trip: raging storms; a man getting his hand trapped in the winch and losing three fingers; a near miss with an iceberg; or someone getting washed overboard? That was all in the past. He was back home, safe and sound, so he just focused on the moment.

The hymn ‘Eternal Father, strong to save’ focuses on ‘those in peril’ whilst at sea – but there is no equivalent for the hidden pressures suffered ashore. Those are generally undocumented – especially the heavy drinking.

After being at sea for three weeks, mainly without alcohol, a trawlerman’s system was fairly clear of toxins. Therefore it did not take too many pints to get a man drunk when he first came ashore. Tolerance levels were lower, even for those with a reputation as ‘hard drinkers’.

This 1949/1950 photo was taken at the Empress Club and shows Bob Bennett (in the centre) with his family and friends. As well as frequenting the pubs, most crewmen also had membership of a social club. This was because they had extra opening hours for members after 3pm.

The daughter of one long- established Hull fishing family told me recently about her severely alcoholic father and stage-four lung cancer mother. Their illnesses were the hidden costs of involvement with the industry, she said. Walter Scott’s well-known phrase ‘it’s no fish ye’re buying – it’s men’s lives’ should perhaps also reference long-term illness.

Those who drank heavily may have been drowning their unresolved grief over the loss of a best friend at sea. Equally, it may have helped a man buck up enough courage to return to the savage seas in the depths of winter.

Sometimes, a drunken trawlerman got into trouble with the law. Local officers knew the pressures on fishermen, and were often sympathetic. There was the story of how a policeman, in conflict with a drunk, ‘squared up’ to him and suggested that they go into a side alley and sort it out man to man.

In a drunken state of bluster, the man agreed. Once out of sight of witnesses, the officer kindly suggested that the crewman take off his made-to-measure jacket to avoid it getting damaged. Whilst the man was reaching behind him to pull his arms out of the jacket, the policeman landed a powerful punch to the solar plexus and down the man went – law and order restored.

Within most fishing communities, there was a powerful matriarchy at work. This especially came into its own when a trawler was lost. The older widows were able to offer support and empathy to the younger ones when tragedy struck.

Whilst her man was at sea for three weeks, his wife was able to collect his basic wage every Friday after midday. This was jokingly referred to as ‘the fish dock races’. Pram-pushing women would dash to the trawler owners’ offices to collect the money. This involved not only wives, but mothers whose bachelor sons were trawling.

In the years following the Second World War, it was still considered that ‘a woman’s place is in the home’”. If her husband could not provide for her financially, he was in some way inadequate – and this clashed with his macho pride.

Sometimes, however, a wife wanted to get out of the house and find a job. There was plenty of demand in fish factories and corner shops, or with one of the big firms along Hessle Road that employed many local women.

But the women’s urge to get out to work sometimes conflicted with the absent trawlerman’s concerns. He might have niggling doubts. What is she getting up to whilst I am far away from home? Now that the kids are old enough for school, what is she doing with her time? Jealousy was a factor, and he did not like the idea of her mixing with men at work.

There was, however, one way in which a fisherman’s wife could earn some extra money without incurring his wrath. That was braiding trawl nets in her front room, or outside the front door when the weather was better. It was a dusty job working with the Manila twine.

Author Jeremy Tunstall claimed that the emotional strains on these marriages resulted in a higher than average divorce rate amongst fishermen compared to the average shore-based worker.

There is one story of conflicting marital interest that did arrive at a happy resolution. The wife of a trawler cook always got upset whenever he headed off to sea. Whilst he was away she listened to the weather forecasts and got worried if storms were raging around Iceland. Even worse was if she read a Hull Daily Mail headline about a man being washed overboard, or of a trawler being ‘lost with all hands’.

In desperation, she went to see the family doctor about her high anxiety. She hoped to get a medical certificate that would force her husband to give up deepsea trawling. But the medical response was: “He was a fisherman when you married him, so you knew what you were letting yourself in for!” Not much sympathy there. Eventually, however, he did settle ashore, and together they opened a fish and chip shop in Hull.

Another unnerving source of insecurity was that Hull fishermen were in a weak position regarding their employment. There were no guarantees of getting another trip. They were unfairly – yet legally – classed as merely ‘casual labourers’. Crewmen had to keep in with the trawler firm’s ships’ runner in order to get another trip.

Added to this, there was an unwritten system on the fish dock of being ‘blackballed’ or ‘sent on a walkabout’. The association of trawler owners had the power to exclude a man from getting another trip out of Hull if he fell out of favour or did not toe the line. Together, Hull trawler barons ruled the fish dock along feudal lines, and with an iron fist.

A man was never told in so many words that he was on a ‘walkabout’. Instead, one of the phrases used was: “I hope you have a good pair of boots.” The innuendo was: “You will need them as you walk from one trawler firm to another trying to get another ship.”

Even a top skipper could be blackballed if he stepped out of line. One view was that ‘if your face didn’t fit, you didn’t get a ship’. This could sometimes be got around, however, with a little backhander to the ships’ runner.

The term ‘backhander’ is generally seen as a bribe outside the fishing fraternity. But amongst the Hessle Roaders, it was an ambiguous term. It could just mean giving an old mate a few bob to help him out because he was out of a ship due to injury.

The women looked forward to the three-day millionaires coming home. It was all fun on the first day. By the end of the second day, however, as one wife admitted to me, ‘he began to get under my feet’.

In comparison to the purely physical dangers of the Arctic Ocean, the home-centred emotional turmoil could seem much more daunting. Sometimes the men felt like ‘a fish out of water’. For some, three weeks back at sea was a time to recover from three days of ups and downs at home.

For many trawlermen, there was a stark contrast between the comradeship afloat when confronting the elements together, and the isolation at home when dealing with emotional family situations alone.

In many respects, the fishing families of Hull had a precarious lifestyle: feelings went unspoken, emotional states were heightened, and income was erratic. They may have been ‘three-day millionaires’, but the threat of poverty hung over them from trip to trip. Paradoxically, these very uncertainties helped the Hessle Roaders bond together and strengthened their community spirit.

After three dynamic days ashore, sailing day soon came around again. Even that was not without its unspoken hazards, in the form of a spider’s web of sailing-day superstitions – but those will have to wait until another time.

This story was taken from the April 2024 issue of Fishing News. For more like this, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.50 here.

Sign up to Fishing News’ FREE e-newsletter here.