Photographer Alec Gill recalls the memories evoked by his pictures of St Andrew’s Fish Dock, taken around 50 years ago as its era was drawing to a close

Hull’s St Andrew’s Fish Dock worked around the clock – 24 hours per day, seven days a week. The only day of rest was Christmas Day. Easter, of course, was very busy – a peak.

The fish dock was a symbolic bridge between its nearby Hessle Road community and the far-off Arctic fishing grounds. The dock was divided between the wet side and the dry side. The wet side handled fish, the dry side handled trawlers.

As a photographer embarking upon my documentary study in the early 1970s, I did not fully appreciate the dock’s endless activity and rich culture. I was naïve. With the benefit of hindsight, I wish I had gone into more dock activities and contacted more firms than I actually did.

Nevertheless, I did what I did, felt at home on the dock, and was accepted by various groups. As with the fishing community, I did not fully comprehend the bigger changes that were taking place at the time. That is, Hull’s fishing industry was dying. Unwittingly, I documented that decline.

Just as an aside: I did my photographic work out of love, self-motivation and my own funds on a grant as a mature psychology student. I was never supported by any official body.

When it came to choosing my photos of Hull’s dynamic fish dock for this feature, it was extremely difficult to narrow them down to a score of images. As a result, it was decided that this issue would cover just the wet side, with the dry side to be featured separately.

Flooded subway

It was nicknamed The Tunnel – the access to the fish dock under the railway lines. Every now and then, after a heavy downpour, it flooded – providing a wonderful opportunity for me to capture a reflective shot – ‘every cloud has a silver lining’.

This cyclist strikes a solitary figure with his silhouette set against the sunlit wall. He is peddling home as the three women behind him head into work.

St Andrew’s Dock opened in 1883 when steam was at its Victorian height, so pedestrians had to play second fiddle to the railways.

First impressions

This image was my very first photograph of Hull’s fishing world, taken on 21 July, 1971. It was a taste of Hull’s fishing cultural life. I was soon hooked, and returned to the fish dock many times – always with my camera.

A couple of years later, my psychology professor told me: “If you want to get on in life, you must specialise.” He meant academically, but I applied it to photography. Thus was born my determination to document Hull’s fishing heritage as it was happening – especially with a focus upon people.

The hunters return

This is the Ross Orion H 235 returning to her home port at sunset on the Humber’s evening tide, on 17 October, 1971. Arctic trawlermen were ‘the last of the hunters’ in the world’s most perilous occupation.

It was because they lived so close to death that the fishing families had such a zest for life. They lived for the moment. For example, the trawlermen’s image was of being ‘three-day millionaires’, with lots of money to spend in a short time ashore.

The old sidewinder trawlers had a sleek elegant look that was a joy to capture.

Lord Line

The grand Lord Line building towered over the eastern end of the former fish dock. In the foreground are Hull’s DB Finn H 332 and Fleetwood’s Arkinholm FD 42. There was always movement within the dock, as trawlers came and went and were moved around from one side to the other. It was a colourful kaleidoscope of change.

The rope looping from above in this picture adds a hint of something happening offstage.

Stanton’s Café

The Stanton family were originally Hessle Roaders, and their dockside café was handed down through four generations to the present day. They served the various dock workers. In the 1930s, an official from a large engineering firm was posted outside Stantons to record the names of workers going in and out of the coffee shop. Business slumped, and the family were worried. The note-taker, however, was so intimidated that he gave up – and the customers returned.

Here are Ann and Peter Stanton in July 2006.

Tiny tugs

Tugs were the workhorses that manoeuvred trawlers within the fish dock. Each returning trawler was towed into St Andrew’s stern first – the reason being that the dock was so crowded, there was no room to turn around when the vessel was ready to set sail again. Before the Second World War, trawlers were only in port for 36 hours (three tides).

Here, the tug Zephyr is moving the Lord Nelson H 330 in Albert Fish Dock, in August 1978. I grew attached to this trawler because I spent time photographing the bobbers landing her fish earlier that year – as you will see overleaf.

Dock furniture

My photographer’s eye was drawn to the beauty of juxtaposing fascinating dock ‘furniture’ with a magnificent trawler in the background. In this case, the Arctic Freebooter H 362 is set against a quayside capstan, forming a symmetry in that each is black and white. The photograph was taken on 8 October, 1972.

During the years of my photographic study, new trawlers came along that were bigger and bigger – especially with the Boyd Line Arctic fleet. Advanced technology also contributed to the overfishing, and unwittingly set the seeds for the collapse of the industry.

Danish snibbies

I always found the Danish snibbies interesting in contrast to Hull’s mighty deep-sea freezer trawlers. These two seiners are the Lindenborg H 62 and Frederiksborg H 93 – doubled-berthed to save money on quay rent.

Behind them is the Lord Line building. It was in full operation then – October 1972. Before the Second World War, it belonged to Pickering & Haldane, which had a vast trawler fleet named with the ‘Lord’ prefix (Lord Stanhope, Lord Talbot, etc).

After rebuilding its bombed site, the company was renamed Lord Line.

Fleet identity

I was intrigued by the romantic names trawlers were given. The Rudyard Kipling H 141 was part of the extensive ‘author’ fleet, along with Bernard Shaw H 67 and Ian Fleming H 396. Other themes were birds (Hawk, Crane), capes (Canaveral, Trafalgar), gemstones (Onyx, Turquoise), inventors (Arkwright, Davy), ‘Lady’ (Madeleine, Rosemary), saints (Dominic, Romanus), and swash-buckling pirates (Buccaneer, Viking).

Danish-born owner Olaf Henriksen adopted an esoteric system. The names of his trawlers always had seven letters (perhaps for luck) and classical Greek or Roman links (Admetus, Calydon, Miletus, Tarchon).

Drydock

This most cavernous space down deep in the William Wright Drydock held a photographic appeal, but it was also tinged with fear. My dread was that the enormous lockgates would break open and a powerful surge of water come thundering toward me! Even if I had been a good swimmer, I would have had little chance.

It never did happen, of course – I am still here! Fear is often more in the head and heart rather than out there. This is the mighty Dane H 144, part of Hellyer’s ‘tribal’ fleet, in the drydock for her Lloyd’s General Survey.

Forest of funnels

Each fishing firm projected a brand image via the adornment of its trawlers in its company livery: its own flag, funnel markings, hull colours and thematic names for its fleet(s).

The ‘H’ stands for Hellyer’s. This firm’s history dates back to the genesis of Hull’s trawling days – from Devon roots to the port’s fishing decline in the 21st century. It had two distinct fleets: tribes (Goth, Mohican) and Shakespearean characters (Othello, Portia).

Hellyer’s, however, was not popular with some crewmen. The grub left something to be desired. And if a man wanted eggs for breakfast, he had to bring them along to the ship’s cook at the start of the voyage.

Deep reflections

I loved it when the fish dock was like a millpond. My eyes lit up as I tried to make the most of the magic moment before a tug chugged along to end the tranquillity.

These two trawlers, photographed in July 1978, belonged to the Ross Group, with the Ross Sirius H 277 centre-stage. Originally, she was the Stella Sirius, built in 1963 in Selby for Charleson-Smith Trawlers. Its fleet theme was to name all vessels after constellations (Polaris, Rigel).

Ross took over this firm, and in 1965 its prefix supplanted the ‘Stella’. Then, in 1969, Ross amalgamated with others to form British United Trawlers (BUT), as the industry contracted even further.

Gangs of 10

Hull bobbers worked in gangs of 10 men. The number of gangs set on a trawler varied between six and 10, depending upon how many kits of fish were to be landed. The teams started at two in the morning.

I wondered why they worked through the night, but the answer was obvious – it was the coolest time of the day, and the perishable fish would be ready to sell on the fishmarket first thing in the morning. As we shall see in the following images, each bobber had his own vital role to play.

Landing the catch

This is ‘belowman’ bobber Tommy Harland in the fishroom of the Lord Nelson H 330. Within each gang, there were four belowmen who sorted the different species into separate baskets.

Hull trawlers caught a wide range of fish in the early post-Second World War years, and each had a local nickname: cod were ‘greens’, haddock ‘dux’, coley ‘blacks’, catfish ‘Tommies’, blue ling ‘whips’, bergylt ‘soldiers’, and a huge plaice was a ‘table topper’. As the basket was hauled up to the swinger at the hatch, the belowman shouted out the nickname – which was then repeated to the catcher ashore.

Swinger at the hatch

Swinger Peter Davis was kept busy by the four belowmen in the fishroom. He worked in close harmony with the winchman ashore. Of all the workers within the fishing industry, the bobbers were the most unionised group, and as a result, they had good rates of pay.

The trawler firms, however, employed their own head bobber. He was responsible for ensuring that each of the firm’s vessels was completely ‘landed out’, ready for the fishmarket sales beginning at 7.30am each working morning.

Often, there was such a glut that many workers took fish home as a perk of the job.

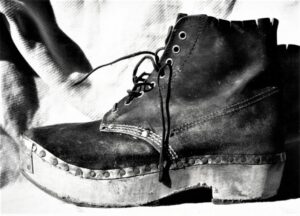

Bobber’s clogs

The click-clack of their heavy high-platformed iron[1]soled clogs, as the bobbers clattered along the sleepy streets leading to the fish dock at two in the morning, is now part of Hessle Road’s community folklore and nostalgic memory. I photographed this clog belonging to my friend John Crimlis.

John, and many other bobbers, had hidden talents that they dared not share with their workmates, for fear of ridicule. John was creative with his hands, and made an excellent model of St Andrew’s Dock as it was in the early 1960s – it is now on show in the maritime museum. Another was a highly qualified, internationally recognised watchmaker.

Winchman

The winchman in the team was highly skilled, and his timing on what was called ‘the wheel’ had to be spot on. This is Wally Broberg, who controlled the baskets of four belowmen as the fish swung from the swinger to the catcher. With a dozen or so trawlers all lined up along the Iceland and North Sea markets, there was a rhythm in the rigging as the wires and baskets zipped back and forth.

This method of landing fish in baskets ashore was almost biblical – an ancient practice from antiquity. Nevertheless, it got the job done.

Catcher or tipper

As the basket of fish swung ashore at speed, catchers such as Colin Ward caught it mid-air and in one swift, smooth movement tipped it straight into a 10st kit – set on scales. Sometimes he was called the ‘weigher-out’ man.

Speed was of the essence. Time was money on the fish dock. Added to that, fish is a perishable commodity, and had to be on the market without delay.

A barrowman quickly removed each kit from the scales. These were later set out in four rows of 10 kits, in 40 blocks or ‘heaps’ of different species and sizes, ready for the arrival of the fish merchants and the frantic sales.

Triangle of trawlers

Until it was pointed out to me by other photographers, I never realised that I was drawn to triangular images or compositions. My picture of three trawlers is obviously an example.

This photo also satisfied my impulse to capture reflections in the still water. The central ship is the Ross Altair H 279 (another within the constellation theme). Sadly, she and others were awaiting their final voyage to the Victoria Dock scrapyard – a short distance up the river Humber – but that is another photo chapter in my documentary work.

Ancient handcarts

These two intertwined handcarts were a ‘still life’ image to my photographer’s eye, with not a person in sight to disturb the embrace. I really like to include people in my photographs. But on the dock, especially at the weekend, there were not many passers-by, so I was drawn to taking images of inanimate objects.

The positioning of these two ancient handcarts – one with a single shaft placed between the twin handrails of the other – it was a neat juxtaposition. The carts belonged to Globe, a well-established engineering firm on the docks.

Artist at work

I never spoke to this guy, so I wonder if this artist ever exhibited any of his paintings from the fish dock. It was only recently, on closer appearance, that I noticed that he has an oriental appearance. So his pictures might even be hanging somewhere in the Far East.

Does anyone know this artist? Is he still in Britain? He was certainly a rare sight on the dock in August 1978. But it was good to see that someone else also saw something beautiful and appealing within St Andrew’s Fish Dock.

This story was taken from the archives of Fishing News. For more up-to-date and in-depth reports on the UK and Irish commercial fishing sector, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.30 here.