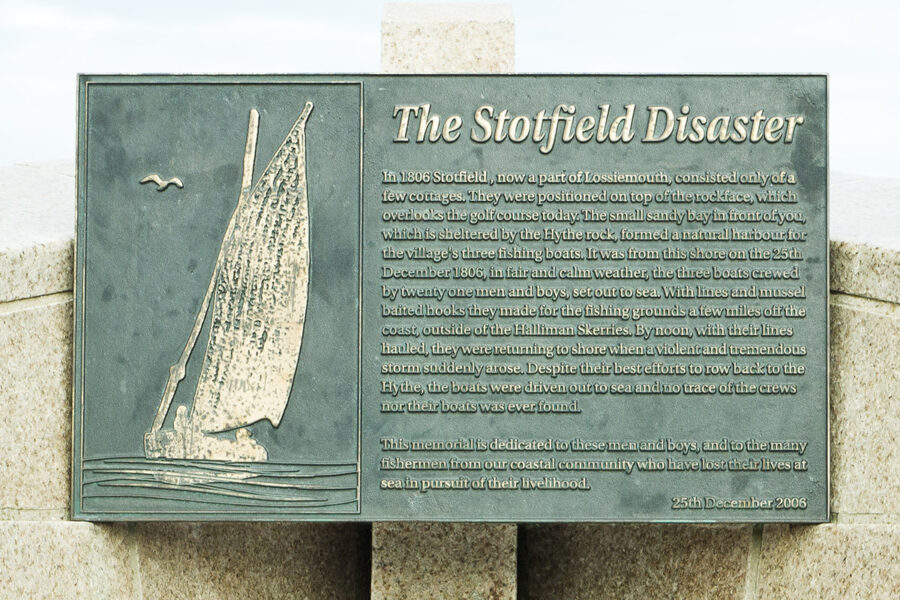

On Christmas morning 1806, disaster unfolded on the North East coast – and the beach at Lossiemouth is said to be still haunted by the memory

By Mike Smylie

Back at the beginning of the 19th century, what is now the town of Lossiemouth consisted of two fishing settlements on its coastal fringe: Stotfield and Seatown. The former occupied the eastern end of the west beach, whilst the latter nestled around the mouth of the river Lossie on the eastern side of today’s town.

In 1806 there were three boats fishing from Stotfield, two from Seatown, and another three from Covesea (Causea), a mile west of Stotfield. The boats were of the ‘scaffie’ type – open boats of up to 25ft in length, perhaps two-masted.

At Stotfield these were drawn up onto what was known as the Hythe, a part of the beach where off-lying rocks gave some protection. The reefs were rich in mussels, and the sandy beach was full of worms, ensuring a supply of bait for the fishermen’s lines. It was not until the end of the next decade that local fishermen followed the herring.

On the morning of Christmas Day 1806, the boats were preparing to sail from Stotfield. The weather had been rough for several days, keeping them ashore, but this day started perfect, crisp and clear, probably very cold, but with blue skies. So the beach was busy with fishermen and others helping to push the boats out.

Out of the blue, young local girl Charlotte, deaf and mute from birth, dashed down to her father’s boat, waded into the sea and started trying to yank him ashore. Unsure what she was trying to tell him, he shook her off and the boat proceeded out into the waves.

Charlotte was known as someone who had the gift of second sight. But with the day so promising and the need to get out to earn some money urgent, any apprehension was ignored.

The boats sailed little more than a couple of miles offshore to fish, beyond the Halliman Skerries. But by mid-morning the wind had started to increase, and by the time the fishermen started to turn back it had risen to almost storm force, pushing the boats away from the land.

Whether they were able to raise sail or were relying wholly upon their oars isn’t clear. The three boats, each with seven crew, were driven into larger seas, in which they soon capsized.

Onshore, the families of the men could only watch in terror at the unfolding disaster. Tragically, no one came ashore. Eighteen men and three boys were drowned.

For Charlotte, lost in grief at the loss of her father and brothr, there was also the terrible guilt of wondering if she could have done more to stop the fishermen setting out. She was so overcome, the story goes, that she left home soon after and was never seen again in the flesh.

But according to legend, that it wasn’t the last time Charlotte would emerge onto the beach. Every Christmas Day, the Apparition of Stotfield is said to appear, waiting on the beach. Those who have encountered her describe a ghostly young woman silently staring out to sea, weeping for her awful loss. Next to her, three deep grooves appear in the sand, like those once made by the keels of Stotfield’s scaffies.

On the scale of the storm, the Aberdeen Journal reported: “On Thursday last [25 December, 1806], a most tremendous gale came on from the south-west. It began in the morning and continued increasing until about 11 o’clock, at which time it had all the appearance and force of a tornado. Its violence was severely felt in this city and neighbourhood.

“The accounts from all parts of the country represent the mischief done by this dreadful gale as beyond calculation – thatched houses unroofed; barns and stables blown down; stacks of corn and hay scattered to the wind; and an immense quantity of large and valuable timber torn from the roots.”

Later that January, the journal published more about the tragedy: “In addition to the melancholy accounts formerly received, of the damage done by the late gale, we have to mention the loss of several vessels on the coast of Caithness.

“Five vessels, names unknown, ashore in the Orkney Islands, 20 to 30 men supposed to be lost. We hear from Elgin that three boats belonging to Stotfield were lost, containing 21 seamen, who had left 17 widows and 42 children, besides aged parents and other helpless relations to lament their fate. Liberal contributions are making for their relief.

“In addition to the melancholy accidents of Christmas Day, we are very sorry to state the following losses: a boat with three men at Burghead; one boat with seven men at Rottenslough, near Buckie; and a boat with seven men at Avoch in Ross-shire, many of them leaving widows and families.”

In this era there were many such disasters affecting small fishing communities, leaving devastation for their families and a scale of loss unimaginable today. The gale of August 1848 resulted in 124 boats lost with 100 lives, whilst in October 1881, 189 fishermen were lost in what has become known as the Great Eyemouth Fishing Disaster. Three months previously, 58 men from Gloup on the Shetland island of Yell had been lost in 10 boats.

Further afield, the Douglas Bay Disaster of 1787 saw 21 Manx fishermen drowned. Off the Mourne coast of Northern Ireland 73 fishermen were lost in one night in 1843, leaving behind 27 widows and almost 100 dependent children.

To encourage incomers into Stotfield in the wake of its disaster, an annual bounty of seven guineas was offered to the first crew of seven men who would settle at Stotfield for three years. The same bounty was offered to a second crew for two years, and a third crew for one year. It’s not known if this was taken up, though the Garden family from Buckie certainly settled in Stotfield about this time.

As for Lossiemouth, the ‘new’ harbour of what was then Branderburgh was built soon after and completed by 1830, becoming well-known in the industry until its fishing demise by the end of the 20th century.

I often wonder if there are still those in Lossiemouth who go out on a Christmas morning to see if they can find Charlotte standing, in Shakespeare’s words, ‘still as the grave’.

This story was taken from the December 2024 issue Fishing News. For more like this, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.50 here.

Sign up to Fishing News’ FREE e-newsletter here.