Photographer Alec Gill recalls his 1975 project documenting the breaking up of a deep-sea trawler as Hull’s distant-water heyday came to its end

Nothing lasts forever – no matter how permanent it might seem. Hull once anointed itself ‘the greatest deep-sea trawling port in the world’. But after we lost the Cod Wars in the 1960s and 1970s, the fishing grounds available to British vessels shrank as 200-mile Economic Exclusion Zones came in for Iceland, Norway and Russia. Hull’s focus on deep-sea trawling made it inevitable that many of its vessels were gradually laid up, sold, decommissioned or assigned to the breaker’s yard.

In that sense, Hull was lucky because it had its own well-established scrap merchant in the shape of Albert Draper & Sons Ltd. It took over the empty slipways on the redundant Victoria Dock to set up its trawler scrapping operations from 1972 onwards.

I came along in the summer of 1975 with my camera, and decided to record as much of the complete break-up of a particular trawler as I could. This coincided with the arrival of the Newby Wyke H 111 at the slipway on the Humber. All in all, I took 355 images of the vessel as she was gradually dismantled, of which the following are a sample.

Newby Wyke H 111

Newby Wyke H 111

This is the 178ft Newby Wyke just after her arrival at Draper’s yard on 16 July, 1975. Prior to being brought to the slipway by two tugs, expensive items – such as the ship’s brass bell and clock, radio and sonar equipment, and life rafts – had already been removed by the owners. Draper’s interest was in her 672GT of scrap metal.

The owners were compensated by the UK government for each trawler they decommissioned. Unlike in some European countries, these payments did not include recompense for the former crewmen.

Funnel

Funnel

As a photographer, I am often drawn to the ship’s funnel or smokestack. This ‘H’ funnel signified the mighty Hellyer fleet. As the Hull trawling industry shrank, Hellyers bought up a number of the failing firms. A sad dimension is that many of these doomed trawlers still had many years of seafaring life left in them. The workhorses of the Arctic trawling grounds were built to last. The Newby Wyke was only 25 years old.

Elvis the king

Elvis the king

This photo shows one of the top cutters at the scrapyard. His name was Eric King, but he was nicknamed Elvis; it might have been his looks, or his surname – or both. Here he is burning off various rigging attachments that were part of the ship’s mast. Deep-sea trawling involved a multitude of complex wires, warps and cables. Soon after the base of each mast was cut away, it was laid on its side and the cutter got to work stripping off the loose attachments. This image also shows how the port side and railings had been removed to enable easy access.

Mast

Mast

Both masts had to be removed so that they did not get in the way of the two cranes during each stage of the dismantling. The large crane is here swinging the fore mast ashore. The land[1]based cutters would then set about cutting it up into smaller segments. Each trawler contained a range of different metals, like aluminium or brass, which were sold separately. The bulk of the scrap metal ended up at the Scunthorpe steel works for melting down and reuse.

Port registration

Port registration

As a historian writing about Hull’s trawling past, I endeavour to pair together each trawler’s correct name and registration number – not always easy, as owners reused the same name over the years for different trawlers. I was pleased to be around to take this photo before Newby Wyke’s H 111 was removed.

Three cutters

Three cutters

This is a favourite scrapyard image. In addition to the three cutters in a line working away on the ship’s mast, Big Jim is held aloft in the metal cradle swinging from the small crane.

Working away with their oxyacetylene torches, the cutters certainly had need of their protective clothing, goggles and breathing apparatus. Toxic fumes were a danger during cutting, though as the work was largely outdoors, that hazard was partly reduced.

Hosing down

Hosing down

There was always a high risk of fire or explosions, not only from the torches themselves, but also from flying sparks igniting nearby flammable materials. As a safety precaution, a jet of cold water was sprayed onto adjacent metal, woodwork and fuel tanks. In this image, the burner is cutting away at the base of the funnel, and sparks are flying about. With the casing cut away, a series of fuel pipes are exposed.

Red Ensign

Red Ensign

The Merchant Navy flag of the Newby Wyke flutters in an easterly wind, as another Hellyer trawler sails out toward the North Sea, heading for the distant grounds.

Bill Draper liked to keep each vessel’s flag flying as long as possible. It was only removed – in a sort of mini-ceremony and with a hint of dignity – at the last moment. A ship’s flag was the heraldic banner of the trawler. The flag, of course, is the civic ensign or ‘Red Duster’ of the Merchant Navy, dating back to 1707.

No more full steam ahead

No more full steam ahead

The removal of the trawler’s funnel was a poignant moment. I was fortunate to be around to capture the big crane carrying it away. The trawler may have begun life as a coal-burner in 1950, and then have been converted to diesel.

Each fleet had its own distinct flag, funnel and hull colour – its own livery. This has always been the case in the maritime world, as I remember well from my days as an export manager in the 1960s. Shipping companies were into ‘brand image’ long before the 21st century.

Anchor

Anchor

An anchor gives stability on the seabed during a storm. It is not meant to end up as scrap metal high and dry under a midday sun. Look closely and there is almost an expression of shock at the base of this marooned anchor: horrified eyes, upturned nose, gaping mouth and protruding ears.

This anchor design is categorised as the stockless class, first created in 1821.

Propellor

Propellor

A propeller gives motion to a ship, driving it forward. A rudder provides direction, but without the power to move, the rudder is aimless. One of many fishing hazards was getting the trawl gear fouled in the ship’s propeller. That was triple trouble: the vessel would be adrift, unable to manoeuvre properly; valuable time was lost trying to free the entangled net; and costly gear could be shredded. The ‘net’ result was less in settling money for the crew.

Bow

Bow

The bow of the Newby Wyke, that once chopped through the icy Arctic waves, is here cut off and swinging aloft. The trawler’s demise is encapsulated in this image.

Newby Wyke was built at Selby by Cochrane’s for the West Dock Steam Fishing Co, which was established in 1922 by the Robins family. They originally came from Ramsgate to Hull in the 1840s with their fishing smacks, and gradually built up their business. They eventually moved into steam trawlers, and their post Second World War fleet numbered several vessels with the ‘Wyke’ suffix.

Oxyacetylene

Oxyacetylene

Welding and cutting with oxyacetylene torches was a highly dangerous occupation. Gas leaks could cause backfires and flashbacks within the equipment. So powerful is an oxyacetylene torch that it can easily cut through 8in of ferrous metal. Of all the oxy fuels, acetylene is the most expensive – so it had to be used at the right moment and to full effect.

This is top burner Dave left-handedly cutting up the bow of the Newby Wyke. His majestic stance reminds me of Edmund Hillary stood on Mount Everest in 1953.

Controlled fires

Controlled fires

Drapers dealt in scrap metal, so had little interest in items like mattresses, lifebelts and tables. They burnt what was superfluous to their financial benefit. Much of the wood was anyway impregnated with the smell of fish.

These ‘controlled fires’ were usually carried out on a Saturday so that the metal cooled off over the weekend ready to start afresh on the Monday – time is money. Most of the oil and diesel was drained off in the early phase, but some was used to saturate the woodwork during the burning stages.

Keeping cool

Keeping cool

August 1975 brought a heatwave. That year’s was the hottest summer on record since 1947.

Scrapping a trawler was very hot work at the best of times – especially for the cutters in their protective clothing. This is boss Bill Draper with the hosepipe, spraying his men to cool them down as they worked. He seemed to have a good relationship with his staff.

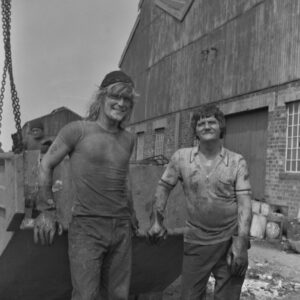

Like father, like son

Like father, like son

This is son and father Phil and Wally, who worked together at the scrapyard. Wally had been a trawlerman sailing out of Hull, and had the world of deep-sea fishing still been prosperous, chances are that Phil would have followed in his footsteps. As with most of the workers I got chatting to at the scrapyard, they were just trying to make a living as best they could for themselves and their families. I found them a great bunch of blokes.

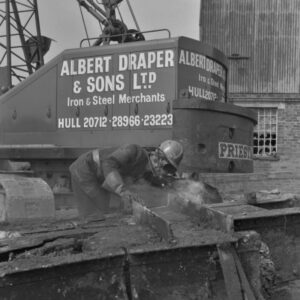

Established 1922

Established 1922

Hull trawlers were primarily (though not always) broken up at their home port – which seems fitting. In fact, there was only one scrap merchant to do the job, and that was Albert Draper & Sons Ltd, established in the city since 1922. Victoria Dock was previously a timber dock, with vast imports of wood from Scandinavia before it closed in February 1970. Drapers modified what had been Earle’s Shipbuilding site, opened in 1863, using the slipways for scrapping trawlers from 1972 to 1981. They broke up between 30 and 40 trawlers, plus other vessels and even a submarine.

Burning bridges

Burning bridges

The burning stages at Draper’s were officially referred to as ‘prescribed’. This involved notifying the Humberside fire brigade that a burning was to happen at a certain time and place.

In this image, two of Draper’s men are directing a hosepipe on the bridge of the Newby Wyke. The intensity of the flames can be seen from the inferno of the wheelhouse windows. The paintwork is charred and blistered. Another purpose of the fires was to get rid of unwanted oil and dirty fuels.

Hoisted up

Hoisted up

Hosepipes are once again in use – this time to clean off mud from the inside hull as a crane is used to drag it ashore. Boss Bill Draper, with his distinctive trilby hat, can be seen on the caterpillar tank tracks of the crane. I think he enjoyed getting into the big crane and helping the job along.

From the Victoria Dock slipway site, the cut-up segments were transported by lorry to Draper’s main scrapyard – not far away on Hedon Road. There the metal would be sorted and stripped down further.

Ship’s telegraph

Ship’s telegraph

There is a nautical expression: “Oil and water don’t mix.” Sometimes – though not always – the chief engineer and skipper aboard a trawler did not see eye to eye. The skipper tended to get the blame for a bad trip – but he would blame the chief if engine problems had been a factor. Regardless, they had to communicate, and this was often via the ship’s telegraph system. From a scrap merchant’s point of view, the ship’s telegraph was made of brass – a metal of some value.

Sparks flying

Sparks flying

Sparks are impressive in a photograph, especially in black and white pictures. But from the cutter’s point of view, when sparks fly, they indicate that a mistake has been made.

The head of the cutting torch is angled between 60° to 90° degrees and has two jets at the nozzle. The outer ring of jets is used to preheat the metal with a combination of oxygen and acetylene. The cutter has to judge the exact moment at which to trigger the central jet of oxygen, and this is when the actual cutting begins.

The flow of the oxygen has to be spot on: too little will slow the job and make a ragged cut; too much will waste oxygen. The central jet of oxygen is then focused on the metal. The cut is made and the metal oxide flows away as dross.

Skipper’s bath

Skipper’s bath

The skipper had the privilege of his own bath in his cabin quarters – though if the fishing was going well, some skippers refused to wash – in case ‘you washed your luck away’. I was glad to be around to take this photograph to highlight a unique aspect of the trawling trade.

This is Wally and Phil examining the old cast-iron bath. I wonder if it had any real scrap value. The left side of this photo looks deep into the engineroom – so perhaps having a bath was a noisy experience.

Protective gear

Protective gear

The excessive heat from the cutting torches, especially once the oxygen jet was opened, created an intense blinding glare. It was impossible to look at this source of light. Specialist goggles were necessary to protect the eyes against the ultra-violet, infra-red and blue light. They also provided protection from flying sparks.

Gas leaks were another real danger, especially if the hosepipes from the cylinders were cut by a sharp object. There were plenty of jagged edges all over the breaker’s yard – so extra care was needed.

Intense heat

Intense heat

This image shows three cutters working away on the upturned hull of the Newby Wyke. The extremely high ‘kindling’ temperatures generated to melt the metal meant that the gas cylinders had to be kept secured, upright and well away from the flames. Care had to be taken to ensure that cylinders did not fall over and damage the valve at the top, as the escaping compressed oxygen was sufficiently powerful to send a cylinder crashing through a brick wall.

Going, going, gone

Going, going, gone

I must admit to being very sad when I arrived at the scrapyard on 28 August, 1975. The slipway where the Newby Wyke had been for the last few weeks was empty. I had become attached to this Hull trawler as she was broken up into smaller chunks and pieces. It was like watching an elderly person slowly slipping away.

Upon reflection, though, my photographic record of her demise has given her some degree of dignity in death. Documenting the gradual break-up of this one trawler symbolised for me the end of an era for Hull as a fishing port.

This story was taken from the archives of Fishing News. For more up-to-date and in-depth reports on the UK and Irish commercial fishing sector, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.30 here.