Brian W Lavery tells the story of fishing’s first ‘celebrity’ – skipper Albert ‘Hurricane Hutch’ Hutchinson – and of the adventuring ex-con-turned-writer who made the Grimsby trawlerman a household name more than 80 years ago

Television has made ‘reality stars’ of many from the fishing industry. Across the world, millions tune into BBC’s Trawlermen and Cornwall: This Fishing Life or Discovery Channel’s Trawler Wars, Deadliest Catch and the like. It has made household names out of people like Peterhead skipper Jimmy Buchan.

Skipper Albert ‘Hurricane Hutch’ Hutchinson – the Grimsby trawlerman who became a household name in the 1930s and 1940s. (Photo: Grimsby Telegraph)

And today, young female fisher and social media influencer Ashley Mullenger of Wells-next the-Sea in Norfolk is bringing a new generation of both genders to consider a life harvesting the seas via her #thefemalefisherman posts on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter.

Even Hollywood superstar George Cooney added to the heroic portrayal of the trawlerman when he played skipper Billy Tyne in the true-life movie The Perfect Storm – the story of the Massachusetts trawler Andrea Gail, which perished in the titular tempest of the film in 1991.

The romanticised narrative of the adventurous fisherman battling the odds in raging seas, so that we can have our fish, is one which has been popular for decades. It still is.

In the 1930s, when radio and print were king, Grimsby skipper Albert ‘Hurricane Hutch’ Hutchinson became arguably fishing’s first reality star.

Hurricane Hutch was widely recognised by his peers as one of the greatest skippers of the northern trawl, even before he was catapulted into the public eye.

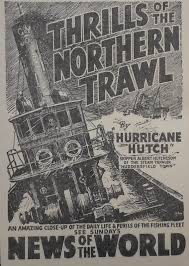

His exploits were serialised in the News of the World. Each week, Sunday paper readers would be told tales of derring-do, of battling tempests, of triumphs and disasters, ‘from no pen other than his own’.

The book derived from the newspaper series, Thrills of the Northern Trawl, published in 1937, was a bestseller.

But the boast that Hurricane Hutch’s stories were ‘from no pen other than his own’ was not quite accurate. The stories were based on his logs – and were most certainly true – but the logbooks were given over to a ghost writer.

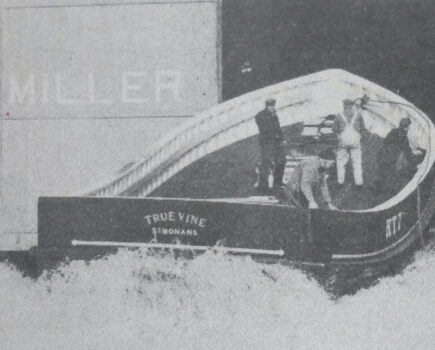

The crew of the Arsenal at work – most of Skipper Hutchinson’s commands were named after football teams. (Photo: Grimsby Telegraph)

That was Captain Allan K Taylor, who often went to sea with the skipper who showed the reading public the true price of fish.

Taylor had befriended Grimsby trawler boss Sir John Marsden, chairman of Consolidated Fisheries, and it was Marsden who recommended Hutch to him.

The skipper had to be talked into it. “Nowt doin’, lad,” was Hutch’s first response, as he wrote in the opening lines of his book.

But Marsden explained that the story of the northern trawl had ‘not been told before’ – and that Hutch and Taylor were the men to tell it. It is not known what was more persuasive – Marsden’s appeal, or the promise of a royalty cheque.

Readers were given insights into the everyday life of the skipper and crew, alongside the tales of storms, great catches and tragedies.

The newspaper stories were illustrated by photos of the skipper and crew at sea, as well as illustrations by an artist.

“In over 31 years at sea,” Skipper Hutch wrote, “I have spent less than four years ashore, mostly in spells lasting an average [of] 36 hours a-tween trips. That’s the price my wife and kids have had to pay for fish.”

Each week, readers heard of the trials and triumphs of Hurricane Hutch. In one episode he recounted the final radio transmission from the Grimsby trawler Jeria, which perished in 1935.

Arsenal GY 48. (Photo: Grimsby Telegraph)

An unknown voice gave a desperate call from the bridge of the doomed ship, which Hutch heard. It haunted him all his life.

“‘Goodbye to my wife… my kiddies! Goodbye, Grimsby… Goodbye Eng…’ The last word was never completed.” Skipper Hutch recounted the event in one part of the series, and later in his book.

Hutch’s tales caught the public imagination, and soon the big bluff skipper from Grimsby was a household name.

Ten years after the success of the newspaper series and the book, Captain Allan Taylor was back with Hurricane Hutch aboard the trawler Stoke City for a historic broadcast.

Taylor was aboard catching up with the story of his friend Hutch when a great storm off Bear Island forced dozens of trawlers to halt fishing – and to stow the trawl.

A poster advertising the ‘Thrills of the Northern Trawl’ series in the News of the World. (Photo: Grimsby History Library.

There were around 150 trawlers from Hull, Grimsby and Fleetwood laid up in the area between Bear Island and Sea Horse Island.

Never one to miss a chance, Taylor decided to make a broadcast from the Stoke City using the ship’s transmitter.

(All the ships Hutch had sailed in over the years had had the names of football teams – the Arsenal, Huddersfield Town and Stoke City being the most notable.)

On 23 August, 1947, amidst the atrocious weather, radio operator Tom Dalton helped Captain Allan K Taylor make history aboard the ship of the country’s most famous trawlerman. Taylor never missed a chance to find an audience – or promote his work.

He transmitted a story he had broadcast the week previously on the BBC Home Service. At the end of the 30-minute broadcast, messages of thanks came in for hours to the radio room of the Stoke City.

Sixty-three trawlers and their skippers were logged, and the broadcast was heard clearly as far away as the Norwegian fjords.

Stoke City, another of Hurricane Hutch’s commands. (Photo: Grimsby Telegraph)

One ship, the Solon, had 18 hands on the bridge to hear it. Others used extension speakers to let the crew enjoy the broadcast. It was the first time anyone had made a broadcast to the fleet from a trawler.

It proved so popular that Captain Taylor gave another half hour’s broadcast the following evening.

According to Hutch, who at the time had 47 years’ sea-going experience, the weather was the worst he had ever experienced on those grounds at that time of the year. There was a northwesterly gale with a tremendous swell, which caused all the ships to lay to. They met with ground fog, and icebergs were sighted.

The story that Taylor broadcast was called ‘The Mountain of Hell’, and told of the writer’s escape from a volcanic eruption in Santa Cruz, Tenerife.

The contrast of the tropical weather in the story and the storms that forced 150 vessels to stop fishing was not missed by the men – or the writer, who never missed a chance for self-publicity. The historic broadcast was recorded by many newspapers.

But the man behind Hutch’s fame was not quite what he seemed.

The urbane BBC broadcaster and famous journalist was also a Glaswegian ex-convict, born in a Gorbals slum. And his own life was even more adventurous than the Boys’ Own hero Hurricane Hutch whom he brought to the world’s attention.

Stoke City GY 114. (Photo: Grimsby Telegraph)

Captain Allan K Taylor was one of the best-known and most successful writers and journalists of his time.

But just six years before he wrote his first article, he had been doing time.

In his autobiography, From a Glasgow Slum to Fleet Street, written in 1949, Taylor revealed how he rose to fame from the worst of beginnings.

He came from crushing poverty, and was born in 1890, just two days after his father died. His teenage mother – the eldest of 19 children – had run away from home in Arbroath, aged just 17.

Taylor recounted how his grandmother came to Glasgow and found him and his mother and took them back to Arbroath. He was seven years old.

At eight, he too ran away from the little fishing port – but was brought back from Dundee a day later. At 10 years old, he made it as far as Aberdeen for three days.

By the age of 12, he was at sea as a trainee steward on a steamer. He told the chief engineer he was 16 and an orphan from Dundee. The sturdily-built boy easily passed for the age he claimed to be.

From there, he adventured his way around the world until the age of 20, when he ended up as a policeman in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).

He deserted when the First World War loomed – one of the rare occasions when someone deserted in order to fight.

By 1914, he was serving with the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). He pestered his superiors to be transferred to a fighting unit.

His requests were refused, so he deserted – again – and avoided capture by simply changing his name.

Taylor joined the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, rose through the ranks and became a company commander. He was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

In 1919, Captain Allan K Taylor DCM joined the South African police – but an affair with a married woman forced a scandalous return to England.

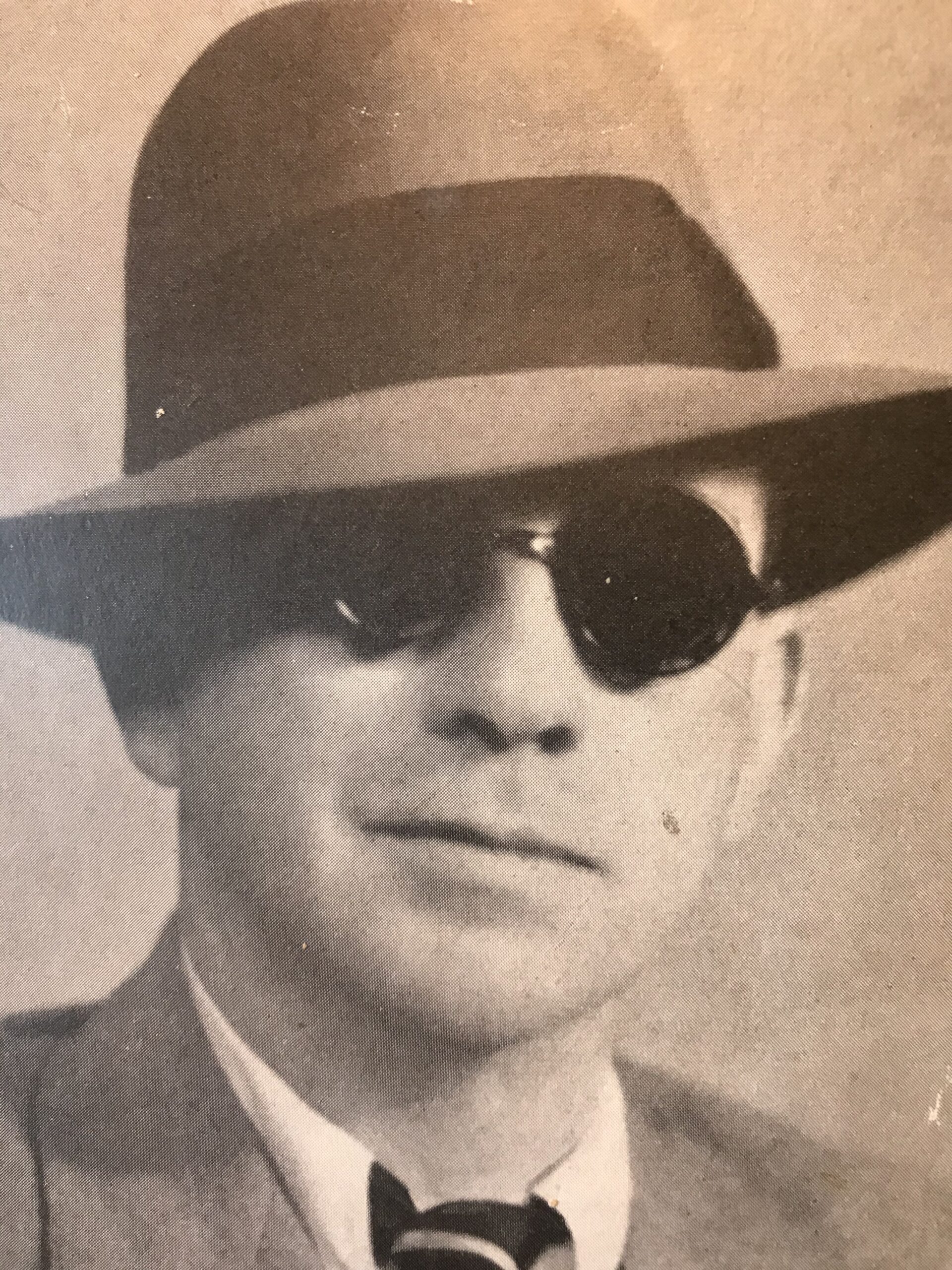

Allan K Taylor’s byline photo from his first days as a journalist.

In later years, Taylor discovered that his mistress had another man – whom he beat within an inch of his life. He also forced that man to sign a £100 cheque to pay for the passage of the woman back to South Africa.

The man – a solicitor – ensured that Taylor was charged with assault and blackmail. The slum kid who became an officer was now a convict. He served four years in Dartmoor – but he used the time to learn to read and write properly.

Jail was to change his life very much for the better – but not before a series of further hardships.

Upon release, he met and married Margaret Ann, a Welsh girl whom he nicknamed ‘Taffy’. He scraped a living in depression-hit Britain as a travelling salesman.

He had now turned 40, was skint and faced being made homeless – and Taffy was expecting a baby. It was she who suggested that he write about his time in jail and expose the cruel conditions.

Taylor approached writing the way he had done everything else in life – head on. He bought six notebooks and a box of pencils. Five days later, on Christmas Eve, 1931, he had written a book.

Now what to do? Taffy typed it up on a machine she had pawned her wedding ring to buy, and posted the manuscript to the News of the World. The newspaper bought it.

Captain Allan K Taylor in later life as a highly successful journalist and broadcaster – despite his colourful past.

Weeks later, the Taylors were celebrating their good fortune in a London hotel. Outside, a billboard read: ‘DARTMOOR FROM WITHIN – by The Mystery Ex-Convict Writer – JOCK OF DARTMOOR!’

A fortuitous turn of events that week was to prove lucky for the Taylors – and the News of the World. There was a mutiny at Dartmoor prison.

Editor Sir Emsley Carr hired Taylor to cover the story. Jock of Dartmoor was now Allan K Taylor – journalist.

From there, Taylor became one of the most successful journalists in Britain. He went on to work for the BBC, and various papers and magazines across the world. He also wrote adventure stories for children in the Boys’ Own Paper and for the BBC’s Children’s Hour.

Hurricane Hutch and the man who made him a star were both born at the end of the 19th century, and lived past the first half of the 20th.

The skipper and the scribe were friends with much in common. They were born into poverty, and lived lives of extraordinary adventure and success. Unlike many writers of adventure today, Captain Allan K Taylor had the experience to back his story-telling – and was undoubtedly as courageous as those about whom he wrote.

Unlike many of today’s ‘celebrities’, Hurricane Hutch’s fame was a true by-product of extraordinary skill and courage.

On Friday, 5 November, 1954, skipper Albert Hutchinson collapsed in the offices of the Grimsby Trawler Officers’ Guild.

He was taken to his home in Carr Lane, Cleethorpes, where he died, aged 64.

Captain Allan K Taylor DCM – if that really was his name – enjoyed success as a writer, journalist, broadcaster and filmmaker for the rest of his life.

The RAMC is still looking for him.

This story was taken from the archives of Fishing News. For more up-to-date and in-depth reports on the UK and Irish commercial fishing sector, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.30 here.