In the ‘Dark Winter’ of 1968, three Hull trawlers perished in as many weeks. Fifty-eight men died in the Triple Trawler Disaster, triggering a transformative safety campaign led by Lillian Bilocca. Brian W Lavery reflects on the story…

Marching on the bosses: Lillian Bilocca leads the women of Hessle Road to storm the docks after a rowdy, angry meeting at Victoria Hall attended by hundreds of women.

I am going over. We are laying over. Help us, Len. I am going over. Give my love and the crew’s love to the wives and families…”

Ten seconds after this radio message in the early hours of 4 February, 1968, the Ross Cleveland disappeared.

Len Whur recognised the voice as that of his cousin, skipper Phil Gay.

Whur was battling to save his own ship, Kingston Andalusite, amid a hurricane and blizzard. He saw the radar ‘blip’ of Gay’s trawler disappear as his own vessel righted.

He shouted back: “Keep her going full speed, Phil, and keep up with me,” but he knew it was too late.

The third Hull trawler in as many weeks perished in the time it took you to read this far.

On 10 January, 1968, the St Romanus and Kingston Peridot had left Hull on different tides, never to return. Little more than a fortnight later, the Ross Cleveland set off for Icelandic grounds.

Lillian Bilocca on the Hull fish dock with her petition clipboard. Her campaign was to transform safety at sea, saving countless lives.

The St Romanus sank with all hands on 11 January, as did the Kingston Peridot on 26 January, and on 4 February, only one man – the mate, Harry Eddom – survived the sinking of the Ross Cleveland.

Incredibly, the St Romanus, skippered by 26-year-old Jim Wheeldon, had no radio operator. More incredibly, this was not illegal. If a skipper had a telegraphy certificate, he could double up. But the wheelhouse VHF radio had a reach of up to only 50 miles, whereas the UHF radio in the operator’s room could reach worldwide.

After the St Romanus and the Kingston Peridot – skippered by 33-year-old Ray Wilson – had been declared lost, Lillian Bilocca and others gathered thousands of signatures demanding better safety.

St Romanus, the first of the three trawlers to be lost.

Lillian’s son Ernie was at the time a deckhand on the Kingston Andalusite. She and her fellow ‘fishwives’ organised a meeting at the Victoria Hall, Hessle Road on 2 February. There were more than 600 women there, and among those speaking was the then local union firebrand John Prescott. Local Labour MP James Johnson was there too, but these women were in no mood for politicians and union men.

Lillian, in her fish worker’s headscarf and apron, addressed the women: “Right, lasses, we’re here to talk about what we are going to do after the losses of these trawlers. I don’t want any of you effin’ and blindin’. The press and TV are here.”

The front cover of the Hull Daily Mail on 5 February, 1968, the day the loss of the third trawler, the Ross Cleveland, was confirmed.

Yvonne Blenkinsop and Chrissie Smallbone joined Lillian on the stage. The two women were well-known in the community, especially Yvonne, a local cabaret singer.

When Mary Denness was called up to the stage, there was booing. Lillian shouted: “Are you booing her because she’s a skipper’s wife? Well, I don’t remember any skippers coming home!” The suitably chastened crowd went on to vote them all in as the Hessle Road Women’s Committee. In the highly charged atmosphere, the women marched on the owners’ offices, but were fobbed off.

Lillian told the crowd: “There is only one way to make these people meet us and hear our case, and that’s by taking action.” Very early next morning, she and a small group of women tried to stop the St Keverne leaving dock. Lillian attempted to board it. She mistakenly thought there was no radio man. He was to join the ship at Bridlington.

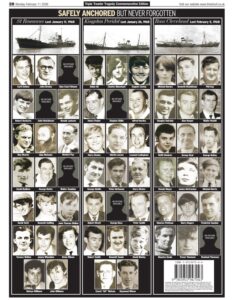

The Hull Daily Mail’s commemoration of the 58 lost men on the 50th anniversary of the tragedy.

Photos of the 17st housewife fighting police, who prevented her from boarding, made headlines. A Sunday tabloid dubbed her ‘Big Lil’. From then on she was lionised and patronised in equal measure by the media – like a cross between Boudicca and Nora Batty.

When the sinking of the Ross Cleveland, skippered by 41-year-old Phil Gay, was announced, the bosses, who had earlier snubbed the women, now wanted to meet.

The women drew up a Fishermen’s Charter demanding:

- Full crews, including radio operators for all ships

- Twelve-hourly radio contact while at sea

- Improved safety equipment

- A ‘mother ship’ with medical facilities for all fleets

- Better training for crews

- Suspension of fishing in winter on the northern Icelandic coast

- A Royal Commission into the industry

News of the loss of the Ross Cleveland reached Hull as Lillian and two others waited on the dockside for the owners. They saw their colleague Chrissie Smallbone, the sister of skipper Phil Gay, being comforted by a clergyman.

The local Transport and General Workers’ Union arranged a meeting in London between the women and minister of agriculture Fred Peart and minister of state at the board of trade JPW Mallalieu.

Sole survivor Harry Eddom recovering in an Icelandic hospital after his 36-hour fight for survival.

Next day, Lillian Bilocca, Yvonne Blenkinsop and Mary Denness, representing the Hessle Road Women’s Group, set off for London with 10,000 signatures, their Fishermen’s Charter and a media circus in tow. Grief-stricken Chrissie stayed in Hull.

Lillian told reporters she would march on Downing Street or ‘that Harold Wilson’s private house’ if she was ignored. Peart and Mallalieu were told by prime minister Wilson, who was in America, that the women were to be helped as much as possible.

That day, the Hull Daily Mail reported: “The wives, led by 39-year-old Lillian Bilocca, were laughed off at first by many in the fishing industry. But now it is accepted that they mean business. What could have turned out to be a hysterical, disorganised protest is now becoming regarded as something of a fighting machine, backed by hundreds.”

In an early interview with me, Mary Denness recalled their arrival at King’s Cross: “It was full of journalists, union men, photographers and TV folk. When we got off, the station was empty, and the platforms were surrounded by those barriers they use on royal visits.”

But at the exit, there were thousands waiting and cheering. A newspaper billboard read: ‘Big Lil Hits Town’.

The women met with the ministers, after which they learned that Harry Eddom had been found alive. His survival became worldwide news.

Minutes before the Ross Cleveland disappeared from the radar, first mate Eddom, dressed in a full ‘rubber duck’ suit, had been chipping ice from the radar scanner. He was knocked unconscious, and was pulled into the boat’s liferaft by 18-year-old deckie John Barry Rogers as it fell from the sinking vessel.

Eddom came to and found himself with the young deckie and bosun Walter Hewitt. Neither was wearing protective gear and both died of exposure within the hour, leaving Eddom alone. For 12 hours the little craft was bounced about, until it washed up on a stony beach.

Eddom dragged the liferaft up the beach and checked his shipmates in vain for any vital signs. He spotted a light in the distance and headed for it, knowing it was his only hope.

He walked miles before being forced to climb a cliff. After trekking over rocky terrain for 15 miles, he reached a shepherd’s hut.

It was locked. Eddom wept. His attempts to force the door were prevented by the pain in his frostbitten hands. He stood against the hut, sheltering from the vicious winds, forcing himself to stay awake. Sleep would have meant certain death. At dawn he was found by a shepherd boy.

Eddom made a remarkable recovery in a nearby farmhouse and was later taken to hospital. A Daily Express reporter broke the story, and ‘The Man Who Came Back from the Sea’ took Vietnam off the front page.

Back in Hull, Eddom’s wife Rita thought herself a widow until the press pack descended on her home.

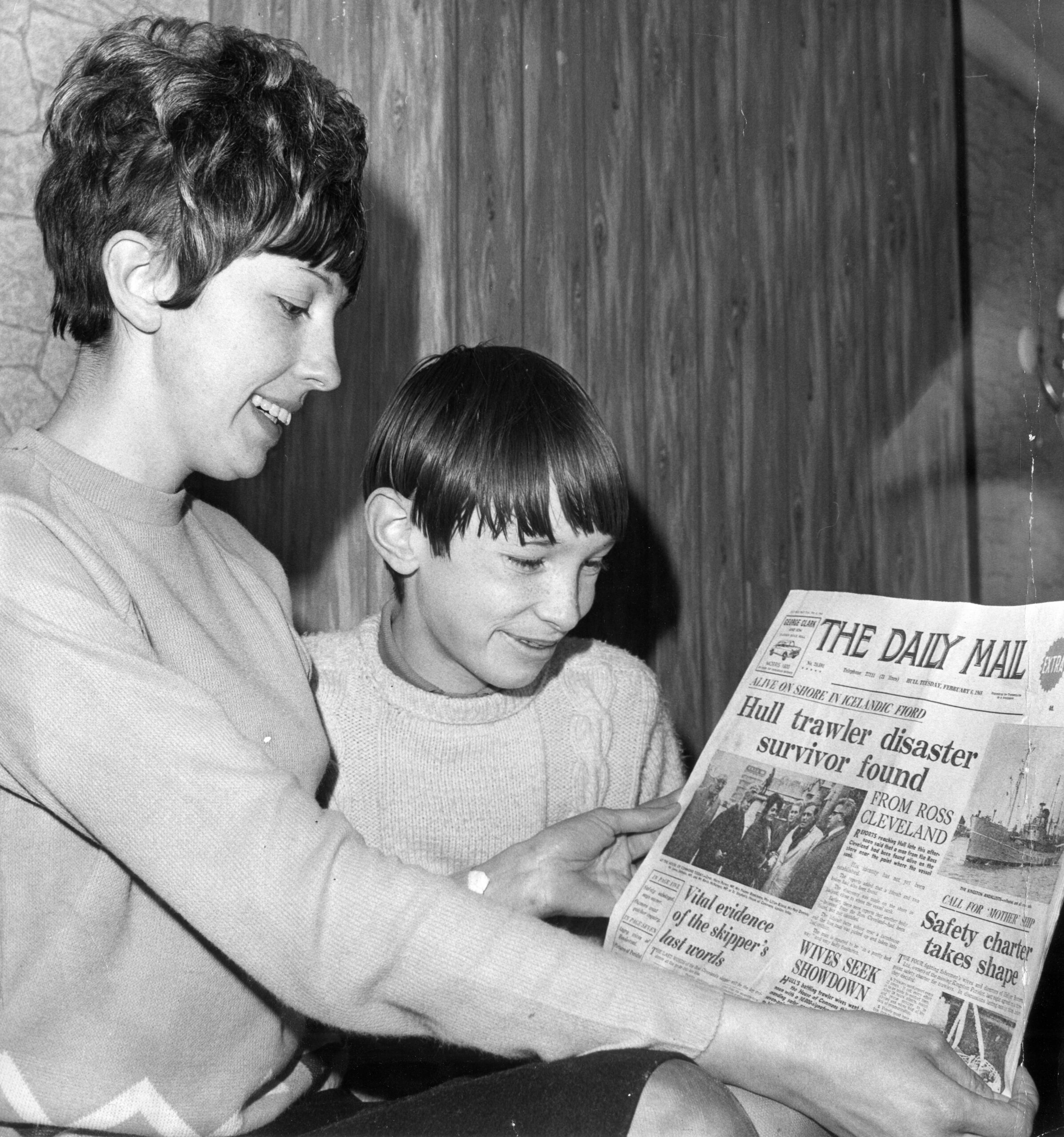

Good news for Rita Eddom, with her little brother, reading about Harry’s survival – papers had dubbed her the ‘36-hour widow’.

The eyes of the world were on the Hull fishing community – and the politicians and owners knew it. The women were delighted with the news of Eddom’s survival and the promises from MPs.

Upon their return to Hull, Lillian told the press and the crowds it was the ‘happiest day of her life’. “We’ve done it!” she said.

Mary added: “Three women have achieved more in one day than anything that has ever been done in the trawling industry in 60 years.”

Their campaign captured the public imagination and shamed bosses and government into immediate action. Fishing was suspended off Iceland until the weather improved. Owners were legally forced to launch a ‘control ship’, the Ross Valiant. A new full-time ‘mother ship’ later replaced it. In October 1968, a public inquiry resulted in the Holland-Martin Report into Trawler Safety. All the demands of the Fishermen’s Charter were met, most before the inquiry, and the remainder soon after.

But weeks of only Icelandic trawlers landing fish in Hull during the bad-weather ban led to poison-pen letters being sent to Lillian and her co-fighters. Yvonne Blenkinsop was attacked in a restaurant by a man who punched her and fled. Letters appeared in the local press.

Skipper Len Whur was Lillian’s fiercest critic, accusing her of putting jobs at risk and ‘interfering in something she knew nowt about’.

Lillian lost her job, and part of the community she had fought to help turned on her. An appearance on the Eamonn Andrews’ Show saw her star fall with stark rapidity.

During banter with the host, Lillian was asked what fishermen did when not at sea. She quipped in her broad Hessle Road accent: “The married ones come home and take out their wives, then go to the pubs. The single ’uns go wi’ their tarts.”

“There was an audible gasp,” recalled Mary Denness. “In Hessle Road the word ‘tart’ has a totally different meaning. It simply means girlfriend, and is not offensive.”

Lillian Bilocca never worked in the fishing industry again. Bosses thought her a dangerous nuisance, and some felt that she had shown up the community. It was two years before she found other work.

She died of cancer in 1988, aged just 59. Her obituary appeared in the Times. I was a young freelance journalist when I wrote it. But at her funeral, only a handful of those who had once cheered her powerful oratory were at the graveside.

Harry Eddom returns to sea, just 12 weeks after his incredible survival.

Harry Eddom, now in his eighties, lives in quiet retirement north of Hull. He has never spoken publicly since the 1960s, and refused several requests to be interviewed – a decision I respect. Remarkably, he returned to sea just 12 weeks after his ordeal. He then had a long and distinguished maritime career, finishing in the 1990s as captain of a Gulf supply vessel.

Chrissie Smallbone became Chrissie Jensen MBE, the award given for a lifetime’s work in trawler safety, as the first woman in the British Fishermen’s Association. She died in 2001, aged only 62.

Mary Denness continued campaigning before a career change. She became a school matron at Eton College, and among her later charges were Princes William and Harry. She passed away in 2017. Her funeral was reported on regional television and in the national press, and hundreds attended.

Yvonne Blenkinsop with her framed Freedom of the City of Kingston upon Hull scroll.

Yvonne Blenkinsop is now in her eighties and still lives in Hull. She has 15 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

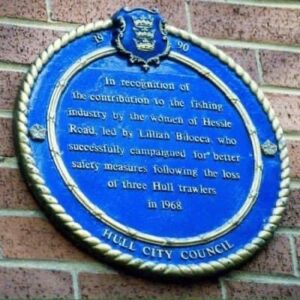

In 1990, Hull Council placed a plaque on the site of the old Victoria Hall. It reads: “In recognition of the contributions to the fishing industry by the women of Hessle Road, led by Lillian Bilocca, who successfully campaigned for better safety measures following the loss of three Hull trawlers in 1968.”

The plaque put up by the city council in 1990 to commemorate the campaign.

For decades, that remained the only tribute to these remarkable women, whose fight for better safety at sea saved countless lives, then and since. Outside of Hull their story was forgotten – a footnote in maritime history.

Today, the phrase I coined for my book title, the Headscarf Revolutionaries, has become shorthand for these brave campaigners. On the day the book was launched in 2015, four plaques were unveiled by the Lord Mayor in Hull Maritime Museum to commemorate their campaign.

Yvonne Blenkinsop, the last survivor, was made a Freeman of the City in 2018. The others were posthumously recognised. Yvonne later accompanied Hull’s three Labour MPs to parliament, to mark the 50th anniversary of the campaign. She was met by Jeremy Corbyn – and John Prescott, who had fought alongside her in 1968.

For me, their true legacy is the innumerable people here today who might not have been but for their campaign. Their story, like their legacy, now belongs to the world.

Brian W Lavery’s book The Headscarf Revolutionaries and its prequel The Luckiest Thirteen are available from: barbicanpress.com and other outlets

Photographs and other illustrations courtesy of Hull Daily Mail, Headscarf Pride and the research archive of Dr Brian Lavery

This story was taken from the archives of Fishing News. For more up-to-date and in-depth reports on the UK and Irish commercial fishing sector, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.30 here.