In the latest of an occasional series remembering the crucially-important role fishermen immediately took on a century ago, John Worrall looks back at how mines helped change the shape of naval warfare.

Britain hadn’t been keen on mines. She considered them sneaky and, worse, a danger to all shipping which, for the premier maritime nation of the time, carried huge potential for own goals. Indeed, after several large warships were mined in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-1905, Britain had tried to get them banned by the 1907 Hague Convention. But while that woolly-worded document ostensibly provided against their indiscriminate use, Germany ignored it after the outbreak, on the grounds that all belligerents had to be signatories and Russia wasn’t.

Mine technology went back a long way, arguably to the Chinese and their early gunpowder, but the real step-change had come during the Franco-German war of 1870-1871 and the deployment of the Herz Horn triggering device invented by German scientist Dr Otto Herz in 1868, which was so effective that it would feature through both World Wars.

It consisted of a soft lead horn containing a glass tube of acid and two electrodes, so that contact with a ship bent the horn, broke the tube and put acid onto the lead and electrodes to create an electric current, which triggered the detonator and thus the charge.

But, to Britain’s sniffiness about mines could be added a Royal Navy aversion to using electricity in water, which resulted in the Naval Spherical Mine triggered mechanically by a ‘firing arm’, contact with which released a spring-operated striker which often didn’t spring, operate or strike. One German submarine commander claimed to have made a long passage with two tangled around his conning tower, in which case he should have given them back, because Britain had only 4,000 mines at the outbreak, far fewer than Germany.

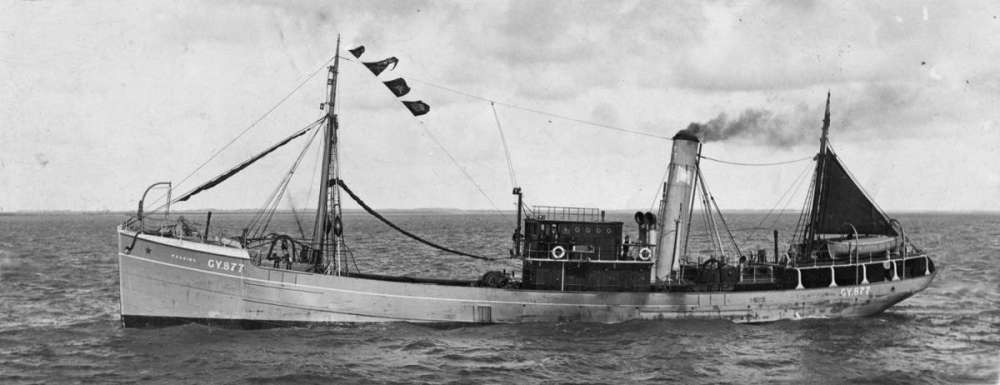

Britain got a close look at the Herz, and other German design features, a few weeks into the war after an ‘egg’ drifted ashore in a rocky cove 20 miles north of Scarborough. Minesweeping officer, Lieutenant Godfrey Parsons, working with the Grimsby trawler Passing GY877, was told to bring it in so that boffins could crack the technology. Enlisting the local TA and watched by a crowd expecting a big bang, he was lowered down a 200ft cliff, removed the detonator and then signalled to be hauled up. Unfortunately, the rope caught round his feet and he was hauled upside down, rendered unconscious and then near the top, the rope broke and he was saved only by a back-up. Eventually regaining his senses, he descended again to put a line around the mine and got the lifesavers’ rocket brigade to fire the other end towards the trawler, which then hauled the egg aboard where the crew hit it with hammers ‘just to see if he had done his job properly’.

The Grimsby trawler Passing lost her bow while minesweeping off Scarborough. (Photograph courtesy of Grimsby Local History Library, Lincs Inspire Ltd).

Passing came to grief a couple of months later after the German light cruiser Kolberg laid a hundred or so mines off the Yorkshire coast, while other cruisers bombarded Hartlepool, Whitby and Scarborough. Very quickly, those mines claimed several ships before minesweeping trawlers from HMS Pekin, the base at Grimsby, began to clear them. Passing was the first sweeper casualty when a mine took off her bow, but her bulkheads held and she was towed, backwards, by the paddle minesweeper Brighton Queen, and beached at Scarborough.

However, the Grimsby trawler Orianda GY 291 hit a mine and sank, and the Aberdeen trawler Star of Britain A239 was badly damaged by another. The following day, the minesweeping trawler Garmon GY 1165 was mined, with the loss of her skipper and five ratings.

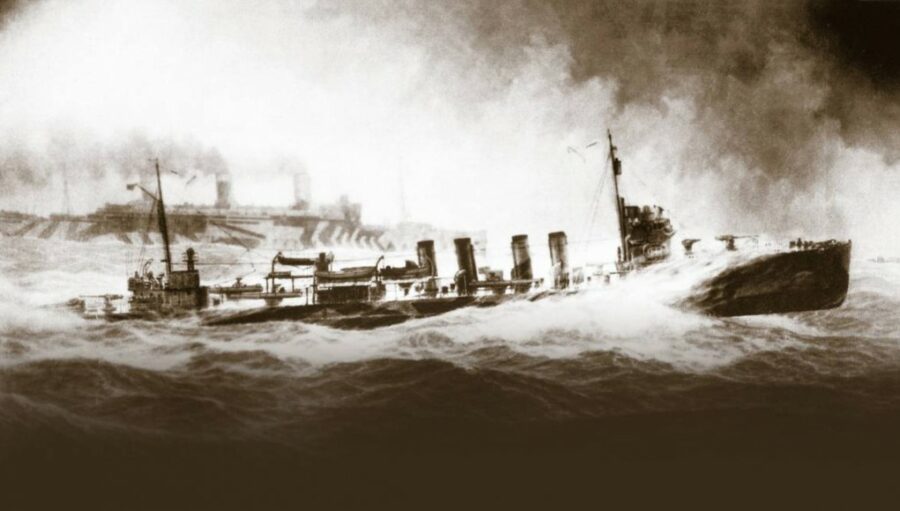

Casualties were inevitable among sweepers, but locating minefields in the first place was the key to minimising merchant losses, and early on in the war the Allies had a couple of intelligence windfalls. One was the grounding of the German cruiser Magdeburg, off Estonia on 26 August 1914, when Russia found naval codebooks aboard. A little later, the light cruiser Undaunted, and accompanying destroyers, sank four German destroyers on their way to lay mines in the Channel, following which a trawler found a safe from one of them in its nets. The safe contained the ‘Verkehrsbuch’, the code used to communicate with naval attachés, embassies and warships. The find was known as ‘The miraculous draft of fishes’.

One occasion when this intelligence came to bear was in August 1915, when the German cruiser Meteor, disguised as a neutral steamer, laid 380 mines in the Moray Firth. She then sank the armed steamer Ramsay, which innocently approached to inspect her cargo, taking the crew prisoner but then making the mistake of sending a coded wireless message warning U-boats of her minefield. Intercepted by British cruisers, she was scuttled and her crew commandeered a neutral fishing boat onto which they also bundled the prisoners. After a stand-off, the prisoners were transferred to a British fishing boat, at which point, the Meteor’s captain, Von Knorr, concerned that the Ramsay’s skipper had been captured in his pyjamas and had no money, insisted on giving him a £5 note. Lord Jellicoe arranged for the money to repaid through diplomatic channels.

In the wider picture, mine-laying and sweeping gradually became a game of bluff and double bluff. Whenever a new field was discovered, British boats sent a Q-message – a top priority radio alert – and trawlers started sweeping. But then a swept field was often quickly re-laid, making a supposedly safe area dangerous again.

Then there was the delayed-action wheeze, with mines designed to sit on the bottom and be released at different times so that a supposedly swept field would have more mines coming up. And there was the case off Ireland’s southeast coast in 1917 – a bad year for British shipping losses – of a minefield constantly being replenished after sweeping. Eventually, the sweeper commander told his trawlers to look busy but do no sweeping and shortly, U44 turned up one night to lay more mines and hit one from the previous shift, her rescued captain complaining about inefficient British sweepers.

Amongst all this, spare a thought for the fish, because explosions killed tons of them. There are several accounts of trawlers, when circumstances weren’t too diverting, suspending their naval work to collect dead fish. You could take the reservist out of fishing but you couldn’t take fishing…

Further reading: ‘The Hidden Threat, the story of mines and minesweeping by the Royal Navy in World War 1’. Jim Crossley. Pen & Sword: pen-and-sword.co.uk

‘North Sea War 1914-1919’. Robert Malster. Poppyland Publishing: poppyland.co.uk

You can catch up on other Defending Britain articles in the series here…