Sailing smacks and box fleets in the late 1800s. Hull trawlerman William Oliver reminisces.

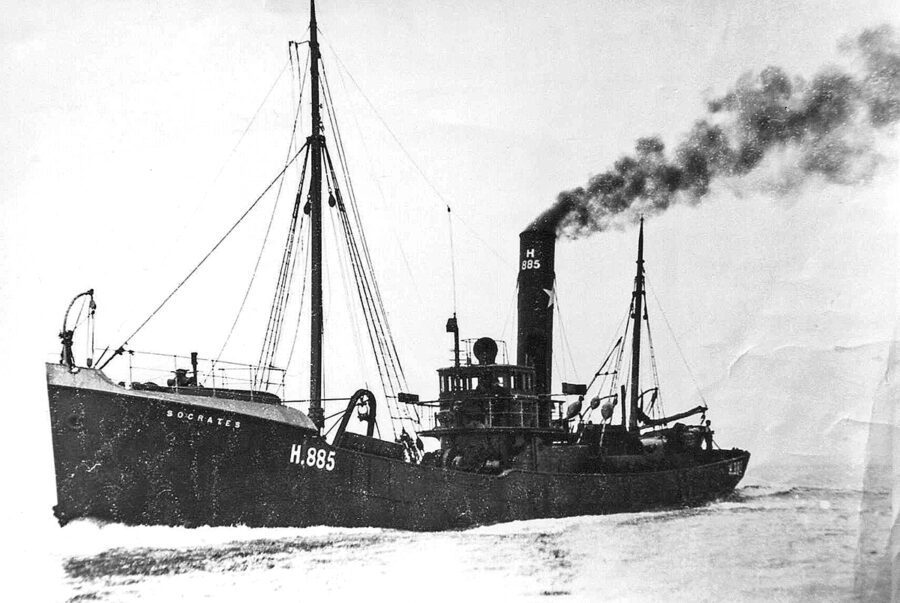

Above: Socrates is a typical steam trawler that fished from Hull in the early 1900s. (Photo: Dr Alec Gill)

My first recollections of Hull Fish Dock were in 1888. I was a small three-year-old boy taken to meet my father returning from sea. He was skipper of a very small steam trawler named the Laurel. She was an old sailing smack converted to steam, and was so small that when she came alongside the promenade at low water, her engine-room funnel was only about two or three feet above the quayside.

While I stood there, the engineer must have thrown a shovelful or two of coal on the furnaces and all the smoke and soot blew in my face and I started to cry. I was hastily removed. I remember nothing more until, as a boy of seven, I was taken by my father on a ‘pleasure’ trip in a vessel named City of Chester. She, also, was an old converted smack, owned by Mr G W Bowman, and, I believe, ended her days as a coal hulk in St Andrew’s Dock.

Of the ‘pleasure’ trip, the thing I remember most is that I was sea-sick for the whole of the nine-day trip.

Each year following this, I went on a similar trip with my father during my summer holidays, and between trips I spent a lot of time on the dock after school hours watching the trawlers and smacks return from sea – as so many other boys of my age did. It was quite exciting to us youngsters, after an exceptionally bad spell of weather, to watch the smacks return damaged by the heavy seas.

I remember seeing one smack return clean swept. Another, the Nonpareil, had her mainmast broken off just above the deck. We were, of course, constantly in trouble with the dock police through swimming in the dock or Humber.

One of my most vivid memories is of the big burst in the dock in 1897. Where the dry dock was situated, it had been decided to excavate a further dock – the St Andrew’s Dock extension. The work was well under way, and blasting operations had been taking place close to the original lock gates.

One fine morning (11 June, I believe) during a spring tide, and while all the workmen, engines, etc, were on the bottom of the new dock, water was noticed gushing out round the lock gates separating the old dock from the new. The workmen dropped their tools and scrambled up the bank sides, engines and machinery were vacated, and at 8.30am, with a loud crash, the lock gates were carried away. It was just about high water, and the main St Andrew’s Dock lock gates were open and ships were proceeding to sea. I was just leaving the dock to go to school when I heard the bang.

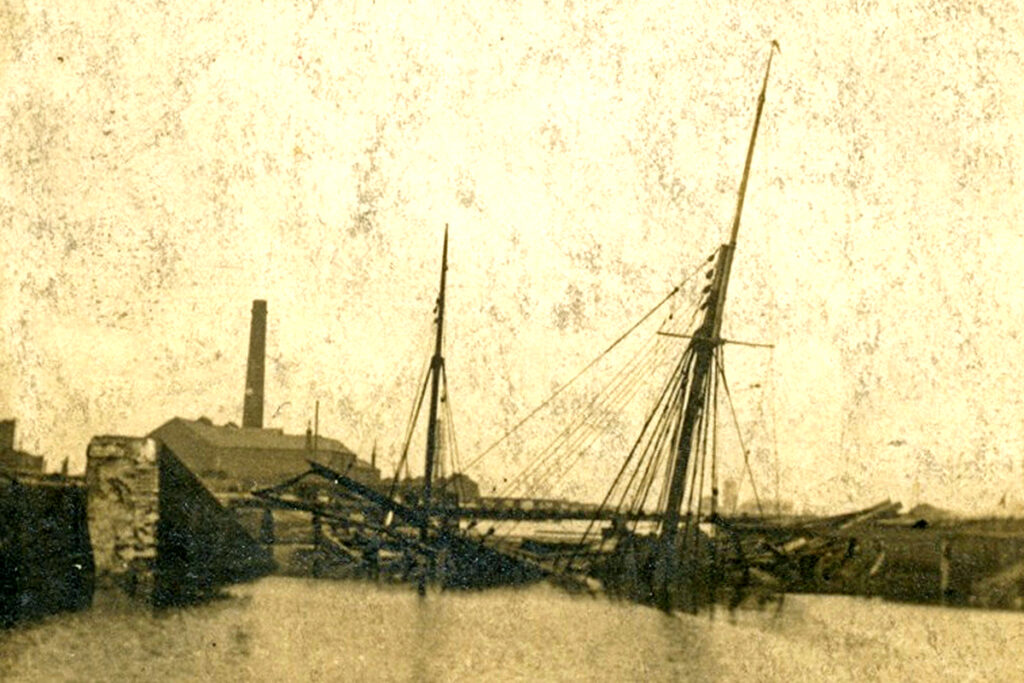

The scene that followed is indescribable. Vessels were torn from their moorings and were hurled with enormous force towards the narrow entrance: smacks and keels were crashing into each other. One smack, the Young Greg, got across the lock pits thwart-ships, but the rush of other vessels broke her in two and she sank, effectively blocking the entrance and preventing other vessels from going forward. It is believed that this saved many lives.

I have been told that not a single life was lost in the whole disaster, though it was pathetic to see the wives and children of keelmen who lived on board being dragged ashore with ropes up the dock side. Fire engines were sent down to the dock to pump water out of the damaged ships, and wagonettes reaped a rich harvest in conveying curious spectators on the dock at 6d. per head. Pumps were fixed along the side of the unfinished dock, and the whole of the water had to be pumped out again. This took over a year.

At 13 years of age my schooldays were over. My father got me a job in the North Eastern Railway Fish Office at the top of the old tunnel-steps on the St Andrew’s Dock. He intended me to be a clerk, but office life did not appeal to me, and I was always in trouble, playing truant on the dock side. I hated the confined life and was determined to go to sea at the first opportunity. After a severe dressing down by the chief, which, no doubt I deserved, I left the office one weekend and I never returned.

Types of fishing craft in 1898

One morning in January 1898, I decided to go down the dock to look for a ship, so perhaps this is an appropriate point to try to describe the type of craft operating at that time.

There were two distinct types – the sailing smack and the steam trawler. The steam trawlers were of two classes: the boxmen and the single boaters. The few smacks operating were all in the box fleets, and there were two such fleets operating from Hull at that time – the Great Northern Steam Fishing Co, and The Hull Steam Fishing and Ice Co, known as the Red Cross, because a red cross was the distinctive mark on the trawlers’ funnels.

The fleets were under the control of an ‘Admiral’ who was appointed by the company for his exceptional knowledge of the fishing grounds, and was always in a sailing smack. They fished in the North Sea, chiefly on the Dogger Bank, and it was the Admiral who selected the particular ground to fish. His vessel carried distinctive marks – a flag on his fore-stay about halfway up and a flag at the masthead. When he hauled his masthead flag down, it was the signal to shoot the trawl.

The Admiral also sent up rockets at intervals during the dark to indicate his position and what tack he was towing on – red stars for port tack and green for starboard. After the night’s catch was cleaned and gutted, it was packed in boxes (hence the name ‘box fleets’), the small boat was launched and the fish ferried from the catcher to a cutter for despatch to London.

These cutters were a super type of trawler, mainly used for cargo-carrying purposes, although they also carried a trawl. They were also under the control of the Admiral who decided when they should leave the fleets for market – the ideal being a cutter to land in London every day except Sunday, so that the Monday’s cutter would have a double night’s catch on board.

The smack Young Greg broke her back when Hull’s new dock was flooded. (Photo: Dr Alec Gill)

For this, the Admiral received a fixed wage per week, and perhaps a bonus in addition to his own vessel’s earnings.

The fleets were served by vessels of the Mission to Deep Sea Fishermen who sold them tobacco duty-free, and also provided the fishermen with woollen clothing, reading matter and writing materials. They usually carried a doctor and a padre on board. These vessels did wonderful work, and were much appreciated by the fishermen. The Mission ships also carried a trawl and fished with the fleet. Before each vessel’s fish was stowed away in the cutter’s hold, a wooden tally with the name and number of the catcher vessel was attached to each box so that the amount of money realised was credited to the vessel concerned.

The sailing smacks carried a crew of five hands, made up of skipper, 2nd hand (both certificated), 3rd hand, decky, and cook (usually a boy). The steam trawlers carried nine hands; skipper, 2nd hand, bosun, 3rd hand (a misnomer, as he is really 4th hand), decky, cook, chief engineer, second engineer, and trimmer.

The smacks stayed out at sea for 10 to 12 weeks and sometimes longer, while the trawler stayed as long as his coal lasted, which in 1898, was usually about five weeks. The boxmen carried no ice so fresh meat and vegetables had to be brought by the cutters from London as required. Clean clothes for the crews of smacksmen were usually put aboard departing trawlers and cutters from Hull, and mail was received the same way, either from London or Hull.

The single boater worked in an entirely different way, as each skipper selected his own ground to work, retained his catch on board, and packed it in the fish-hold covered with ice. When the skipper considered he had sufficient to make a payable trip, he proceeded direct to Hull and landed his catch there. An average North Sea trip would take about 10 days.

Icelandic fishing was beginning to get into its stride, although in 1898 the fish, except halibuts and plaice, was considered of poor quality, and did not realise much. The usual Iceland voyage took about three weeks. There were also a few long-liners, with wells in, about this time – the Richard Simpson, Bloodhound and Staghound belonging to Humber Steam Trawling Co (now defunct), Portia (C Hellyers), Sardius and Peridot (Kingston Steam Trawling Co Ltd), are names which come to my mind – but for some reason line-fishing did not make progress in Hull.

My first adventure

On a January morning in 1898, I went to the St Andrew’s Dock to look for a ship. I was 13 and a half years old. I wanted to go in a smack so that I would be away a long time, as if I made a short trip I had good reason to think that my father, who, at that time, was a very successful skipper fishing the North Sea, would stay ashore to prevent me going to sea.

Before noon, I had signed on with a smack, the Emperor, belonging to Robins. When I gave my age correctly, I was told I would not be allowed to sail until I was 16. In my eagerness, I admitted to making a mistake in my age, and signed on as 16. So, on 14 January, I sailed through the lockpits of St Andrew’s Dock as a cook, with William Haycock as skipper.

Of the next two or three days, I prefer to say very little. I did no cooking, but spent most of my time stretched out in the small engine-room in the agonies of sea-sickness. After two days of this, I begged the skipper to send me home as soon as we joined the fleet, but he made it quite clear that he would not send me in until it was possible to obtain a relief for me. But, by the time we joined the Great Northern fleet, I was much better and I tried my inexperienced hand at cooking. The results must have been grim, but my terrible meals cannot have had many ill effects on the digestive organs of the crew as one of them, at any rate, lived to a ripe old age. I refer to Mr George Blackshaw, the third hand, who died in December 1947, at the age of 74.

We arrived home at the end of March. I received the princely sum of 12s per week; the liver money was divided into four shares and I was to receive 3d out of the decky’s shilling, but I never got it, as he said he charged me that for teaching me cooking. The Emperor was in dock for a fortnight, and at the end of that time, to my very great surprise, the skipper asked me if I intended to sign on for another trip. I never dreamed of having a second chance, but I signed on again, and we sailed away in mid-April on what proved to be the last of the Emperor’s boxing trips. We duly joined the Great Northern fleet but after about five weeks, the skipper was informed that as far as smacks were concerned, it was to be disbanded. An Admiral was coming out in steam, and the ‘GN’, as it was commonly known, was henceforth to be entirely of steam trawlers.

We sailed across the North Sea and joined the Red Cross fleet off Horns Reef. I well remember my 14th birthday – on June 1, 1898 – when I was crouched in the sheet of the mainsail, sewing the reef lacing through the eyelet holes to haul down our second reef while it blew half a gale. We remained with the Red Cross until August.

End of the sailing smacks

I have purposely said little of the routine of my life on the Emperor, as I was too young to understand how things were managed. We fished, of course, with a beam trawl. We always preferred to shoot on the port tack as we could then lower the trawl straight overboard, but if it became necessary to shoot on the starboard side, the trawl warp and bridles had to be passed under the bottom before the trawl was lowered.

The skipper was very good to me, but the mate gave me a tough time, which perhaps I deserved. I knew my compass, and could knot and splice and mend a plain hole in the net.

When the smacks were disbanded from the fleets, many were sold to Iceland and Faroe – some were converted into coasters, and for many years carried cargoes along our coasts. A few went single-boating, including the Bluebell and Village Belle, belonging to Lengfield and Ward. They did not survive long, as they were unable to compete with the steam trawlers using the otter trawl.

Read more from Fishing News here.