Researchers at Aberdeen University say that sprats have recovered strongly in the Clyde.

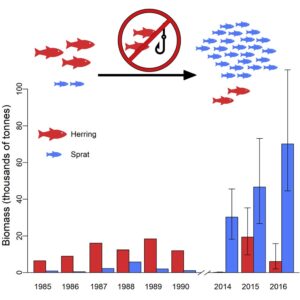

They say the biomass is now four times higher than it was in the late 1980s, and sprats are now ‘highly dominant over the historically more abundant herring’.

Research has discovered huge shoals of sprat in the Clyde, some more than 1.2 miles long and over 100ft deep. The Aberdeen study found numbers had increased 100- fold since the late 1980s.

The researchers say this is an example of an unexpected recovery of a marine system that has been affected by fishing pressure.

They say many marine ecosystems have been adversely affected by human activities, but some are now recovering due to reductions in fishing pressure.

The Clyde has been subjected to ‘intense’ human activity for over 200 years. “This region once had productive fisheries for herring and other fish, but these disappeared at the turn of the century,” say the researchers.

“Using acoustic surveys of the pelagic ecosystem, we found that the Clyde Sea supports 100 times as many forage fish as in the late 1980s. However, herring has now been replaced by sprat, despite virtually no fishing on herring for 20 years.”

They say a combination of a warming sea, bycatch of herring in the prawn fishery and susceptibility of herring to poor recruitment may have contributed to this unexpected recovery.

“We compare this to similar unexpected ‘recoveries’ involving unforeseen ecosystem effects, such as the return of hake to the North Sea, the recent expansion of the pelagic squat lobster Munida off Peru, and the increase in scallop numbers on Georges Bank.

“The lack of a current sprat fishery in the Clyde presents a unique opportunity to develop an alternative industry for its seafaring community – ecotourism,” say the researchers.

They say that people will pay to see marine life such as whales, dolphins and seabirds that will in time – if not already – ‘be drawn in by the abundance of forage fish now present, further restoring the biodiversity of the region after centuries of overexploitation’.

Relative abundance of sprat and herring in the Clyde 1985-2016.

The Aberdeen study, published in the journal Current Biology, has shown that although there are still herring in the Clyde, where it was once a major fishery, sprat are 100 times more numerous.

The last time herring and sprat were measured in the 1980s, the combined biomass was a quarter of what it is now, says the study.

The researchers worked with Marine Scotland Science on the research vessel Alba na Mara, using advanced sonar processing techniques to discover the shoals and estimate the numbers of each species over three years from 2014 to 2016. The total weight of sprat in 2016 was estimated at over 70,000t.

Elaine Whyte, secretary of the Clyde Fishermen’s Association, said the findings were ‘not a surprise’ to Clyde fishermen. She said they had been aware of the increasing stocks for some years, but it was good to see science backing up their experience on the grounds.

But while the biomass was increasing, the size of the fish was not, and the age classes of some pelagic stocks were less than would have been expected 30 years ago.

“Herring are getting to a certain age and then just disappearing – they’re not maturing. We don’t know whether they’re moving somewhere else or just not living that long,” she said, adding that the change seemed to have happened in the past decade.

“Fishermen think it could be things like chemicals in the water – it’s something we hope Marine Scotland will be looking at.”

Dr Joshua Lawrence, who led the Clyde study, which was funded by the Marine Alliance for Science and Technology Scotland, said: “The Clyde is famous for its herring, but although there has been virtually no fishing pressure on herring in over 20 years, it is the sprat population that has bounced back, not the herring.

“We can only speculate as to why this has happened – perhaps it is the warming seas, which may favour the sprat, or their more favourable reproduction strategy, as herring need particular gravel beds to spawn, whereas sprat do not.”

He told the BBC that the researchers also found large concentrations of krill in the Clyde, which is a major food source for the fish and for other larger animals such as minke whales, which are known to visit the area.

“So there are large populations at various levels of the marine food chain, which tells us that the Clyde’s marine ecosystem is faring better than previously thought, despite centuries of overexploitation.”

Professor Paul Fernandes, fisheries scientist at Aberdeen University’s School of Biological Sciences, said it was ‘fantastic’ to see these parts of the food chain recover. This should, in time, lead to recovery of the populations of the larger animals that feed on them, he said.

He said the findings presented a dilemma for fisheries managers and the local seafaring community. A sprat fishery could operate in the river, but a more sustainable and more lucrative opportunity could present itself through developing whale watching in the Clyde.

Anecdotal reports suggest more whales and dolphins appearing in the Clyde, and the university had detected large numbers of porpoises in the area in a related study, he said.

Professor Fernandes told the BBC: “As these whale populations themselves recover, they may find their way into these rich feeding grounds, much as they once did, and I am sure people would pay to see them, as they do in other parts of the world where marine ecosystems have recovered.

“The key will be to do this responsibly to ensure a long-term future for the Clyde’s historic seafaring community.”

This story was taken from the latest issue of Fishing News. For more up-to-date and in-depth reports on the UK and Irish commercial fishing sector, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.30 here.