Skiff fishing for Mourne herring using drift-nets on inshore grounds off the Co Down coast from harbours like Annalong and Kilkeel is one of the most traditional and unique fisheries in the UK.

The historical importance of the skiff fishery is shown by the fact that a separate allocation is given each year specifically for Mourne herring in the Irish Sea (area VIIa). Countless fishermen have kick-started their careers by shaking Mourne herring out of drift-nets during what has typically become an intensive but extremely brief seasonal fishery.

David Linkie looks back to October 2013 and a stand-out Monday night on Annalong skipper Peter Chambers’ 28ft boat Priscilla Jean N 50

Hauling well-fished nets on Katy’s Pride and William Alexander off Annalong.

Securely wedged into a convenient corner, sitting on top of a pond board aft, avoiding nodding off proved too strong to fight as Priscilla Jean headed towards Kilkeel shortly before dawn with 40 crans of herring onboard. Waking up a few minutes later, half expecting to find the crew laughing, it was a relief to see that all but skipper Peter Chambers were also dozing, even though two were leaning back uncomfortably upright against the wheelhouse.

Having been at sea for 14 hours, during which time the crew had hauled and shaken 6.5t of herring out of three trains of anchored drift-nets in less than ideal conditions, this was totally understandable, not least because they still had to box and land the night’s catch alongside Kilkeel fishmarket shortly before 8am.

Being able to witness the skiff fishery was a unique and fortuitous experience in which timing was crucial, as the boats were at sea for just five nights spread over a period of two weeks of the year in early autumn.

Although licences for the Mourne herring fishery issued by the former Department of Agriculture and Rural Development were available from 2 September, and some good marks had appeared along the shore between Ballymartin and Annalong, inshore skippers had to wait until local and visiting midwater trawlers finished landing Irish and Celtic Sea herring into Ardglass for processing by local processors.

When favourable market and sea conditions coincided for the first time in the second week of October, fishing was only possible on one night before a northerly gale meant an immediate stop. Having kept a watchful eye on XC Weather, receiving a text saying ‘The beginning of next week looks like giving as good a chance as you will get, but there are no guarantees’ led to a hasty ferry booking from Cairnryan to Belfast.

Priscilla Jean’s crew hard at it on a long night.

Shaking herring out of the net.

The Annalong-based Priscilla Jean hauling herring drift-nets.

Ben Wortley lifts out lug stones while shooting the first train of drift-nets off the transom.

Setting the second set of nets from the middle pond.

Amazing Grace II working as a remote sonar to help locate and define a mark of herring.

The first herring of the night start to come aboard…

… before being shaken out of the net.

Ready to haul the next section of net.

The Mourne mountains loom large over Priscilla Jean and William Alexander, berthed in Annalong harbour.

The traditional Mourne skiff Anna in the Mourne Maritime Centre at Kilkeel.

The finished product – filleted Mourne herring, processed for export by Kilkeel Kippering Company within hours of being caught.

Landing Mourne herring at Annalong.

Herring being hauled aboard William Alexander, as decades of tradition are maintained.

Katie’s Pride and William Alexander hauling in close proximity.

The traditional Mourne skiff William Alexander hauling off Annalong.

Hauling in progress on Priscilla Jean.

Starting to box and land herring after Priscilla Jean returned to Kilkeel harbour at dawn.

Andrew Maybin takes a well-earned breather while hauling the last train of nets.

Scooping herring through a scuttle down into the fish hold.

Arriving at Kilkeel on Sunday teatime, there was just time to see Priscilla Jean and William Alexander leaving the harbour and pick up a key from the B&B before pulling up at Annalong harbour, where Ashley Shields was waiting on Silver Darlings to run me off to where the lights of four boats could be seen clustered together a mile offshore.

The quickly arranged offer ‘to cruise around the skiffs as they started hauling’ to get different photos was extremely welcome, and once again highlighted the much appreciated help that Fishing News regularly receives from the industry it represents.

With a northeasterly force five wind, sea conditions were less than ideal for the job in hand, although the presence of a localised but dense mark of herring, standing six fathoms high in nine fathoms of water, provided motivation.

Having shot an hour earlier, the boats moved to pick up their winkies to begin hauling shortly after Silver Darlings arrived in the vicinity.

Although Mourne boats use traditional nylon herring nets, most of which were bought from Fraserburgh some 40 years ago and which, with annual maintenance, continue to give sterling service, today they are worked in a different manner, reflecting the inshore nature of the fishery. While still referred to as drift-nets, the Mourne herring nets are fished with anchors ‘trammel’-style. Drop or lug stones, usually house bricks, are attached to the footrope at two-fathom intervals using half-fathom strops. These are made from sisal twine, which in the event of the drop stones coming fast when hauling, part easily to prevent damaging the net.

Rigged in this manner, the headline of the herring net stands around three to three and a half fathoms high.

Depending on the size of their boat, Co Down skippers use nets that are either six or seven and a half score meshes deep, cut down from the favoured 18-score Scottish nets. The minimum mesh size permitted in the licence regulation is 54mm.

Again relative to vessel size, skippers tend to rig a ‘train’ of gear with between four and six nets, each of which is 36 yards long. Smaller boats use just one train, and bigger vessels two. Gauging the distance between the winkies, either when a train is fishing or when the nets are flaked on the quay, gives an immediate indication of the extremely small-scale nature of the gear used, and therefore the fishery itself.

With no buff or headlines to worry about on the surface, Ashley Shields skilfully manoeuvred Silver Darlings into some great places for photographs. This was helped by the fact that Richard Hill on the 18ft Plymouth Pilot Katie’s Pride N 38 and Ryan Newell on the rebuilt traditional Mourne skiff William Alexander B 48 had shot their nets less than two boat lengths apart, and were therefore hauling closely parallel to each other.

Both these boats, like Priscilla Jean 100 yards to the east, were hauling their nets for reasonable amounts of herring. As a result, less than two hours later, Silver Darlings and Harbour Lights followed a well-fished Katie’s Pride into Annalong harbour, where a sizeable contingent of locals were waiting to watch Mourne herring being landed, such is the lure of the historic fishery, which used to mean so much for previous generations.

In the early hours of the next day, Priscilla Jean and William Alexander landed a combined total of 79 crans (12.8t) in Kilkeel harbour after a relatively short and successful night’s fishing, when each boat only shot each train of nets just once.

A freshening northeasterly wind the following morning immediately cast doubts on the prospect of going off later that evening on Priscilla Jean, but Peter Chambers thought that conditions would quieten down. As the day wore on, the presence of gannets constantly diving to feed gave welcome signs of another night’s possible successful fishing.

This thinking proved accurate, and after taking the nets, which had been hauled onto the quay that morning for cleaning, back onboard at 5pm, Priscilla Jean left Kilkeel 30 minutes after William Alexander, before punching north along the shore for an hour as the sea fell away.

With a beam of 10ft and powered by a 67kW Beta Marine engine, Priscilla Jean was based on a Cygnus GM 28 hull, moulded and fitted out by G Smyth Boats Ltd in 2009.

With no sonar, initial location of herring relies heavily on traditional signs of oil on the surface, water colour and bird activity, together with reports during the day from potting boats working in the vicinity. While still a couple of miles from where herring had been taken the previous night, Ryan Newell reported the welcome news that William Alexander had found a good mark half a mile further offshore than the previous night, and that sea conditions were probably workable – certainly by the time it came to haul – assuming that the boats shot.

Mourne skippers prefer to shoot on the edge of darkness, when herring tend to give a little bit of a kick that can result in them meshing well. The fish are also liable to scare more easily if the nets are shot when there is still too much light in the evening sky.

A subsequent update indicated that the mark was moving unpredictably, although still giving good concentrations of herring tight to the bottom. Tracking the mark was helped by the fact that Joey Chambers had come out from Annalong on Amazing Grace II to serve as a remote sonar to help the two skippers at sea that night track the edges of the mark – which, although heavy, was no more than 150 yards across, and therefore called for accurate shooting.

With the fish continuing to prove flighty, Priscilla Jean crossed the shoal of herring several times until, with a clear pattern of waypoints displayed on the Maxsea plotter, and Amazing Grace keeping station at the southern end of the mark, skipper Peter Chambers called for the upwind winkie to be released, followed by the leader rope and the first anchor.

As the first net started to run out of the aft pond across the transom rail, Ben Wortley lifted the neatly stored lug stones out to the port side to ensure that the gear shot away cleanly. To starboard, Andrew Maybin ensured that the headline corks went away clear, while also clipping a spring rope onto the headline at each net joining.

With the Rapp triple-roller pedestal hauler mounted on the starboard side abaft the wheelhouse, and therefore closer to amidships than other boats participating in the Mourne herring fishery, Priscilla Jean’s crew worked a spring or bush rope to help haul the boat up to the gear and take some of the weight off the nets. The spring rope led through a small captive bracket mounted forward on the gunwale rail before going on to the vessel’s Hydroslave pot hauler.

Having shot the first train of six nets with the tide, skipper Peter Chambers immediately started tracking the mark again in preparation for shooting a second tier of four nets. Twenty minutes later, the third winkie light of the night was activated before being dropped over the stern less than 100 yards away from the first train, and fairly close to one of William Alexander’s two trains of nets.

Reasonably satisfied with the location of the nets in relation to the marks, Peter Chambers headed for the lights of Annalong one and a quarter miles to the west, where two more crew were waiting to be picked up at the harbour. Shortly after Priscilla Jean was alongside, where takeaways had been delivered, William Alexander left the harbour to start hauling.

In just over two hours since being shot, the first net of the night started to come aboard containing what at first sight appeared to be a reasonable showing of Mourne herring. The drift-nets on Priscilla Jean were hauled with two crewmen standing at the hauler, the forward one of whom also periodically hauled the spring rope.

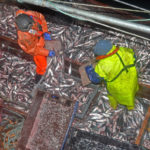

The nets were hauled across the beam by three men standing along the port gunwale taking handfuls of yarn. When a new section of net was lying across the beam, the hauler was stopped to enable the five crewmen to shake the herring out of the net down into the main central fish pond. On completion of this five- to 10-second operation, the hauler was engaged again and the labour-intensive process repeated.

After three nets were hauled, Priscilla Jean swung to the gear for a few minutes while an estimated four crans of herring were scooped towards two deck scuttles leading to the fish hold. On clearing the deck, hauling commenced again with a similar quantity of prime Mourne herring glistening in the sea as they neared the surface. Given the density of the mark he had shot on, Peter Chambers was slightly disappointed with the quantity of fish coming aboard.

Over on William Alexander, skipper Ryan Newell reported that they had hauled their first train of nets for a similar lower return than possibly anticipated. This suggested that the herring were moving sluggishly, and not swimming as strongly as they can at certain times when tidal conditions suit and natural instincts determine, when bigger numbers of fish can be meshed. In other words, these were the typical frustrations of passive fishing compared to using mobile gear.

Looking to shoot away for the second time shortly before 11pm, Ryan Newell reported locating a big mark of fish a quarter of a mile inside where the two boats had shot earlier in the evening.

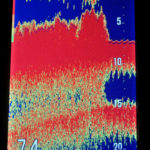

Priscilla Jean’s Koden sounder subsequently displayed this mark as standing nearly five fathoms high in a water depth of seven and a half fathoms. Lining up the intended shot indicated that the mark was considerably longer than the train of six nets. This offered greater leeway in terms of when to start shooting away, which was a welcome bonus in view of the fact that Amazing Grace had berthed in Annalong harbour for the night as the tide ebbed.

Immediately on taking the last net, bridles and winkie of the first train aboard, Priscilla Jean’s crew had started to overturn the gear from where it had been stored in the port side pond aft to the central transom pond, ready for shooting away again.

Good to go again, the train of six nets was shot away for the second time at 11.30pm. As the second winkie was left astern, Peter Chambers turned Priscilla Jean to head back along the gear to see how the nets were lying in relation to the mark shown on the sounder. It was quickly apparent that the nets seemed to be well placed in the middle of the mark, so things were looking good, as long as the herring played their part.

With low water less than 90 minutes away, when the slack tide and the first of the flood can sometimes result in herring giving an extra little kick, and the surface of the sea swathed in moonlight, it was thought that the next two hours of soak time for the second train would coincide with more than favourable conditions.

Priscilla Jean’s second train of nets proved to be slightly lighter fished than the first, as a result of which an estimated 12 cran (2t) of herring were lying in the hold shortly after 1am. Clearly, considerable work lay ahead for the remainder of the night.

Although the second train of nets was quickly laid aft ready for shooting again, skipper Peter Chambers was reluctant to do so, in case the nets fishing in the big mark yielded large quantities of fish. Reports from William Alexander of heavy nets confirmed the wisdom of this precautionary course of action, with Peter Chambers opting to have a look at the first net, which had been fishing for little more than one hour, before deciding what action to take.

In struggling to pull the nylon bridles through the pedestal hauler, the considerable weight of herring in the first few fathoms of the first net was immediately apparent. The initial elation voiced by Priscilla Jean’s crew that their nets were well fished was quickly tempered by the realisation that several hours of hard work lay ahead.

While all forms of fishing are demanding, for sheer intensity, skiff fishing, as experienced over the next three and a half hours, is undoubtedly strongly placed on the leaderboard.

Although only 36 yards long, the first net yielded around seven crans of herring, which after considerable strenuous effort came over the hauler like a solid cascade before being shaken from the net. With limited deck space to work in, clearing the well-fished nets was almost as physically demanding as bringing them onboard. The need to stop hauling at one and a half fathom intervals meant that almost as soon as the lads at the hauler managed to gain some momentum on the net, it was immediately lost due to the need to stop and shake.

Shortly before the first net was aboard, a well-fished William Alexander steamed past on her way into Kilkeel, before landing 40 crans (6.5t) of herring.

At the joining of each net, Priscilla Jean’s crew took a well-deserved breather, after ensuring that the central reception pond over which the nets were shaken was cleared of herring by scooping them down into the hold through the deck scuttles.

Seeing herring lying more than a foot deep repeatedly disappear off the deck spoke volumes for the size of the fish hold on a 28ft boat, which was eventually filled with 30 crans (4.8t).

Hopefully the photographs accompanying this feature illustrate better the exhilaration and intensity experienced while hauling more than 30 crans (5t) of herring from six nets better than any words can.

Shortly after 6am, Peter Chambers opened a scale-splattered wheelhouse door and set a course for Kilkeel, six miles distant to the south.

On berthing alongside the fishmarket, the crew started to land the night’s catch two boxes at a time, from which the herring were immediately transferred into bins for filleting by Kilkeel Kippering Company Ltd, located just a few hundred yards from the point of landing.

The weather-dependency of the fishery was highlighted the following night, when the boats were kept in harbour by force six to seven southeasterly winds. With the wind coming round to the land the following afternoon, the sea that had grown quickly fell away, enabling Priscilla Jean and William Alexander to leave Kilkeel harbour on the flood tide. Although the skippers searched along the shore for several hours, the marks of spawny herring appeared to have been broken up by the seas, with the result that neither boat shot.

This brought home just how fortuitous the timing had been that made my 600-mile round trip fully worthwhile.

Historic Mourne herring fishery

Generations of families living in Co Down have been supported to various degrees by the Mourne herring fishery, which for decades was successful and therefore of considerable socio-economic importance.

Being a labour-intensive and seasonal fishery that coincided with a quieter time on farms in the adjacent hinterland, the Mourne fishery shares many similarities with the previously important crofting fishery in the Scottish Highlands and islands.

Old ship’s lifeboats sourced from Belfast and Dublin were frequently used alongside traditional Mourne skiffs, which were between 18 and 35ft in length.

Skiffs were traditionally clinker-built, frequently using iroko planking on oak ribs. They were double-ended boats, with a low freeboard for rowing, and rigged with a standing lug and jib sail for speed and ease of manoeuvre.

Older fishermen vividly recall more than 60 skiffs from Newcastle, Annalong, Kilkeel and Greencastle bar on the northern shore of Carlingford Lough participating in the Mourne herring fishery in the 1960s and 1970s.

A succession of Mourne skiffs, including William Alexander, were built by John Kearney in Annalong in the early 1970s, before they were manhandled by local fishermen the relatively short distance downhill to be launched in Annalong harbour.

For a number of reasons, stemming from a growing lack of interest due to a combination of factors – including little financial reward, the increasing availability of RSW herring and a shortage of fish along the Mourne shore, where shoals of herring previously came in each autumn to spawn on the gravelly bottom – the fishery died off coming into the 1990s. During the next 15 years, very few skippers spent any time looking for herring on the shore, even though there were increasing visual signs each year. Only from 2007 onwards did the fishery start to attract an upsurge of interest from some local inshore skippers, as the traditional herring drift-nets started to be hauled out of net stores in Annalong and Kilkeel.

By this time, however, the biggest obstacle was an acute lack of quota. In 2012, the failure to implement expected swap deals resulted in the annual quota of 30t being taken by local boats in just one night’s fishing.

Fortunately, the local POs were able to secure swaps with Ireland that brought in an additional 100t of quota for the 2013 fishery.

In recognition of the historic importance of the Mourne herring fishery to previous generations, members of the ANIFPO made a further 100t of quota available for lease, in the expectation that the community would be able to reap the benefit of this in years to come.

For four years after this trip in 2013, a similar pattern of short-lived herring fishing activity prevailed, when the various unpredictable factors involved, including weather conditions, fish location and market opportunities aligned sufficiently to give a small-scale fishery for a few nights each year.

However, there has been no participation in the Mourne skiff fishery since 2017, although herring continued to appear off the Mourne coast in late September and early October.

The main reason for this was that the local prawn and scallop fisheries were reasonably buoyant, thereby minimising the incentive to rig out for a few nights’ work in a highly labour-intensive fishery.

Quotas and licences continue to be available for a traditional fishery to take a small percentage of the Irish Sea herring stock, which is healthy and holds MSC accreditation.

At the time of writing this feature, it was thought that given favourable conditions, a couple of boats might shoot a few nets, with the intention that any herring caught would be sold to raise funds for Covid-19 charities, in order for the fishing community of Co Down to show their appreciation for frontline key workers.

Mourne skiff William Alexander

The traditional Mourne skiff William Alexander B 48 was extensively refurbished and restored to prime condition in 2009.

After it had been of the water for 15 years, during which time the hull quality deteriorated considerably, to the point of almost becoming derelict, while standing alongside Newry Road in Kilkeel, Gary Hill decided to buy the hull from Michael Collins and rebuild it.

Earlier, various shipwrights had more or less condemned the skiff, which was built by John Kearney at Annalong in 1973 for the Collins family of Kilkeel.

After moving the skiff indoors, Gary Hill, who although a tradesman, had no previous experience of boatbuilding, started to rebuild the skiff’s wooden hull, helped by his fellow non-experienced enthusiasts Leonard McCarvary and Billy Edmund, who previously owned the skiff Silver Spray. Less than 10 weeks after restoration work started, during which time the three men worked 430 hours, William Alexander, which is named after Gary Hill’s dad Alexander and late grandfather William, was refloated for the first time since 1994.

The extent of the rebuilding work is shown by the fact that in addition to fitting new frames throughout the hull, a new stem head and apron were also fitted. New planks, fashioned from yellow pine and secured with 2,500 copper nails, were fitted from the bilge keels up to the gunwale rail, which was also renewed, as were the thwarts, foredeck and deck boards. A new foremast and wheelhouse were also made.

In additional to their large carrying capacity, one of the key characteristics of a Mourne skiff is a large central fish hold, accessed through flush deck boards. This traditional arrangement gives the double advantage of allowing herring to be directly shaken out of drift-nets into the hold, from where they are easily accessed for boxing and landing in harbour.

The only item that did not require significant attention was the original Perkins 4236 diesel engine, which kicked into life at the first attempt and is now running as sweetly as ever.

William Alexander has an LOA of 32ft, beam of 10ft 6in and a 3ft draught.