In the second of an occasional series to remember the crucially important role fishermen took on a century ago, John Worrall looks back at the start of the hostilities in the North Sea following the outbreak of World War 1.

So rapid was the chain of events that led to the declaration of war on August 4, 1914, that it caught those at the sharp end by surprise. Both navies had plenty of big, new warships but no match practice, and Britain, for its part, hadn’t lost a ship through military action since that little local difficulty with Napoleon a century before.

But those warships, armoured, heavily-armed and fast, were immediately compromised by two new factors – mines and submarines – which would change forever the face of naval warfare. Shortly after war was declared, Admiral Jellicoe, in charge of the Grand Fleet, and afraid of accusations of a lack of fighting spirit, wrote a paper saying that he would not pursue a retreating enemy because they might be feigning flight to lure his ships onto torpedoes or mines. He was aware, as Churchill said later, that he could lose the war in an afternoon.

His point was endorsed in October 1914, just after U9 had sunk those three British cruisers of the ‘Live Bait Squadron’, when the Second Battle Squadron was conducting gunnery practice off County Donegal, safely away from any submarine threat as it thought, only for the almost new Dreadnaught Audacious to be sunk by a mine.

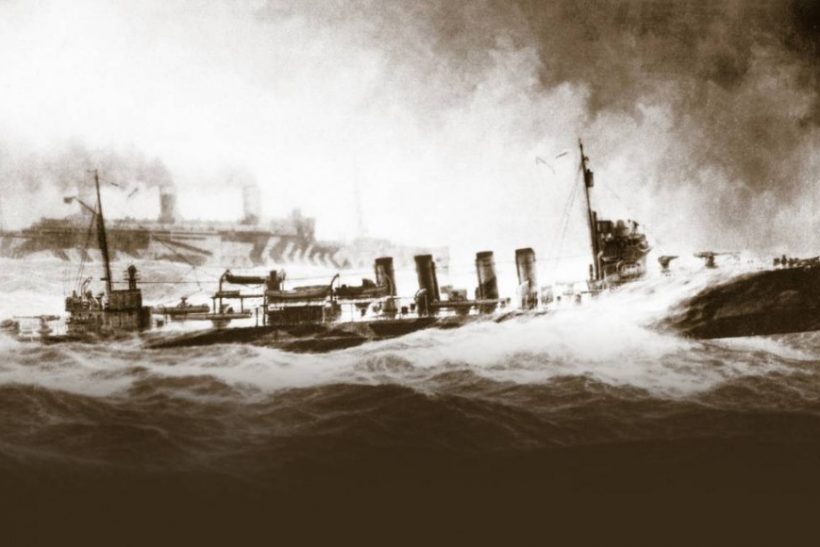

Thereafter, no British or German Dreadnaughts were sunk by any method, partly because they dared not go anywhere without massive mine-sweeping efforts running before them. That was a real palaver, with the outdated gunboats and destroyers that initially did the job having limited range, and therefore sailing with coal piled on the decks. But mines still caused far more damage to Royal Navy and merchant shipping than torpedoes or gunfire.

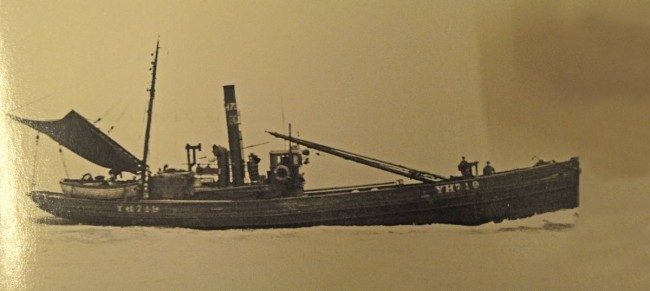

So fishing boats were put onto mine clearance and anti-submarine work, part of their advantage being that they could function in heavier weather and, with their fish holds full of coal, were able to stay at sea for three to four weeks. Some were bought by the government, while others were chartered if they were under 10 years old and able to steam 1,000 miles at eight knots.

The charter fee was based on 12% per annum of the trawler’s then value, which in turn was calculated at £18 per ton gross, with £40 per nominal horsepower of the machinery and boilers, depreciated at 4% per annum.

Sweeping was mainly done in harbour approaches, rather than ahead of warships, for which trawlers were too slow, and by 8 August, less than a week after declaration, at least 114 were in service or fitting out. Many of them were in Lowestoft, which became the chief depot for sweepers.

And there was urgency from the outset because three significant minefields were discovered very early in the piece; one during the first few days off Southwold, sown by the Königin Luise, which was duly sunk by the Harwich Force, only for the Force’s flag ship HMS Amphion to be sunk by its mines.

Then, in late August, the Yarmouth steam drifter, City of Belfast, fishing near the Outer Dowsing, found two mines in its herring nets and thus discovered the Humber minefield. The skipper kept fishing but when another exploded in a net the following day, he decided discretion was the wiser plan, abandoned the gear and went home. On that occasion, 10 steam drifters – rather than more powerful trawlers – were sent from Lowestoft to sweep the field, working in tandem pairs to get enough pull on the sweep wire, but two of them, the Lindsell and Speedy, hit mines and sank.

The third minefield was off the Tyne where, in October, the North Shields trawler/sweeper, Lily, was mined with the loss of seven of her 10 crew, the three survivors being picked up by the Great Yarmouth drifter, Oakland.

And by then, with much of the fishing fleet commandeered and a thus much reduced fishing effort, the inescapable law of supply and demand was coming to bear.

While food prices nationally rose by 78% between July 1914 and November 1916, fish rose by 132%, and even when, in January 1918, the Fish (Prices) Order belatedly laid down maximum prices, those maximums, as The Times observed, quickly become minimums.

Naturally enough, boats which kept – or returned to – fishing, usually with skippers and crews too old to be reservists, did well. Even dogfish found a market. According to Fishing News, Scottish boats working herring from Yarmouth during the 1915 season ‘only had to go to sea and put their noses in the fishing grounds to come back with at least a catch worth £100’. In Dundee the previous December, the sprat fleet had been getting over £2 a cran compared to six or seven shillings (30-35p) pre-war.

But those Scottish boats working from Yarmouth were doing the right thing, donating a cran of herring each in 1914, to be sold for the Belgian Relief Fund in support of Belgian boats and families that had fled to England just before the Germans moved into Ostend. The following year, they made the same donation to the British Red Cross Society.

And not only mariners, but also the British public, appreciated the sweepers’ efforts and were always sending them presents, to the extent that the Naval Store Office ‘got fed up with handling the stuff’. Donations were particularly thick at Christmas – balaclavas, helmets, socks, cardigans, pullovers and scarves etc. At the Invergordon depot in Scotland, a large barrel of walnuts turned up, addressed to ‘the officer i/c mine-sweepers’, but, not properly sealed, it was moved to a small outbuilding at the town hall because the depot was short of storage.

When they returned to collect it a few days later, there was a roll of dirty canvas lying on top of it, out of which fell a dead Chinaman who had been brought ashore from an oil tanker, the outbuilding apparently serving as a temporary morgue. There was some debate on whether the nuts might be infected with whatever disease had killed him, but one of the sweeping skippers pointed out that if they didn’t eat the shells or crack them with their teeth, no-one should catch anything, which turned out to be the case.

We’ll have more from John Worrall on fishermen in WW1 very soon. Head to our news page for more from Fishing News.

In the second of an occasional series to remember the crucially important role fishermen took on a century ago, John Worrall looks back at the start of the hostilities in the North Sea following the outbreak of World War 1.

So rapid was the chain of events that led to the declaration of war on August 4, 1914, that it caught those at the sharp end by surprise. Both navies had plenty of big, new warships but no match practice, and Britain, for its part, hadn’t lost a ship through military action since that little local difficulty with Napoleon a century before.

But those warships, armoured, heavily-armed and fast, were immediately compromised by two new factors – mines and submarines – which would change forever the face of naval warfare. Shortly after war was declared, Admiral Jellicoe, in charge of the Grand Fleet, and afraid of accusations of a lack of fighting spirit, wrote a paper saying that he would not pursue a retreating enemy because they might be feigning flight to lure his ships onto torpedoes or mines. He was aware, as Churchill said later, that he could lose the war in an afternoon.

His point was endorsed in October 1914, just after U9 had sunk those three British cruisers of the ‘Live Bait Squadron’, when the Second Battle Squadron was conducting gunnery practice off County Donegal, safely away from any submarine threat as it thought, only for the almost new Dreadnaught Audacious to be sunk by a mine.

Thereafter, no British or German Dreadnaughts were sunk by any method, partly because they dared not go anywhere without massive mine-sweeping efforts running before them. That was a real palaver, with the outdated gunboats and destroyers that initially did the job having limited range, and therefore sailing with coal piled on the decks. But mines still caused far more damage to Royal Navy and merchant shipping than torpedoes or gunfire.

So fishing boats were put onto mine clearance and anti-submarine work, part of their advantage being that they could function in heavier weather and, with their fish holds full of coal, were able to stay at sea for three to four weeks. Some were bought by the government, while others were chartered if they were under 10 years old and able to steam 1,000 miles at eight knots.

The charter fee was based on 12% per annum of the trawler’s then value, which in turn was calculated at £18 per ton gross, with £40 per nominal horsepower of the machinery and boilers, depreciated at 4% per annum.

Sweeping was mainly done in harbour approaches, rather than ahead of warships, for which trawlers were too slow, and by 8 August, less than a week after declaration, at least 114 were in service or fitting out. Many of them were in Lowestoft, which became the chief depot for sweepers.

And there was urgency from the outset because three significant minefields were discovered very early in the piece; one during the first few days off Southwold, sown by the Königin Luise, which was duly sunk by the Harwich Force, only for the Force’s flag ship HMS Amphion to be sunk by its mines.

Then, in late August, the Yarmouth steam drifter, City of Belfast, fishing near the Outer Dowsing, found two mines in its herring nets and thus discovered the Humber minefield. The skipper kept fishing but when another exploded in a net the following day, he decided discretion was the wiser plan, abandoned the gear and went home. On that occasion, 10 steam drifters – rather than more powerful trawlers – were sent from Lowestoft to sweep the field, working in tandem pairs to get enough pull on the sweep wire, but two of them, the Lindsell and Speedy, hit mines and sank.

The third minefield was off the Tyne where, in October, the North Shields trawler/sweeper, Lily, was mined with the loss of seven of her 10 crew, the three survivors being picked up by the Great Yarmouth drifter, Oakland.

And by then, with much of the fishing fleet commandeered and a thus much reduced fishing effort, the inescapable law of supply and demand was coming to bear.

While food prices nationally rose by 78% between July 1914 and November 1916, fish rose by 132%, and even when, in January 1918, the Fish (Prices) Order belatedly laid down maximum prices, those maximums, as The Times observed, quickly become minimums.

Naturally enough, boats which kept – or returned to – fishing, usually with skippers and crews too old to be reservists, did well. Even dogfish found a market. According to Fishing News, Scottish boats working herring from Yarmouth during the 1915 season ‘only had to go to sea and put their noses in the fishing grounds to come back with at least a catch worth £100’. In Dundee the previous December, the sprat fleet had been getting over £2 a cran compared to six or seven shillings (30-35p) pre-war.

But those Scottish boats working from Yarmouth were doing the right thing, donating a cran of herring each in 1914, to be sold for the Belgian Relief Fund in support of Belgian boats and families that had fled to England just before the Germans moved into Ostend. The following year, they made the same donation to the British Red Cross Society.

And not only mariners, but also the British public, appreciated the sweepers’ efforts and were always sending them presents, to the extent that the Naval Store Office ‘got fed up with handling the stuff’. Donations were particularly thick at Christmas – balaclavas, helmets, socks, cardigans, pullovers and scarves etc. At the Invergordon depot in Scotland, a large barrel of walnuts turned up, addressed to ‘the officer i/c mine-sweepers’, but, not properly sealed, it was moved to a small outbuilding at the town hall because the depot was short of storage.

When they returned to collect it a few days later, there was a roll of dirty canvas lying on top of it, out of which fell a dead Chinaman who had been brought ashore from an oil tanker, the outbuilding apparently serving as a temporary morgue. There was some debate on whether the nuts might be infected with whatever disease had killed him, but one of the sweeping skippers pointed out that if they didn’t eat the shells or crack them with their teeth, no-one should catch anything, which turned out to be the case.

We’ll have more from John Worrall on fishermen in WW1 very soon. Head to our news page for more from Fishing News.